When The Diving Bell and the Butterfly first flitted over the turbid waters of my cinematic consciousness some years ago, I didn’t give it much thought.

When The Diving Bell and the Butterfly first flitted over the turbid waters of my cinematic consciousness some years ago, I didn’t give it much thought.

To be perfectly honest, my initial reactions were almost entirely incidental. The first, a mild curiosity over the fact that its director shared a surname with the famous pianist and composer, Artur Schnabel. And the second, an amusement at the juxtaposition of two such disparate objects in the film’s title itself. A diving bell, huge and ponderous and archaic, yet life-giving. And a butterfly, all gossamer wings and rebirth and weightless, fleeting beauty.

In other words (and yes, I shouldn’t be so surprised), the perfect title for this film, which is available on NETFLIX STREAMING and YOUTUBE($).

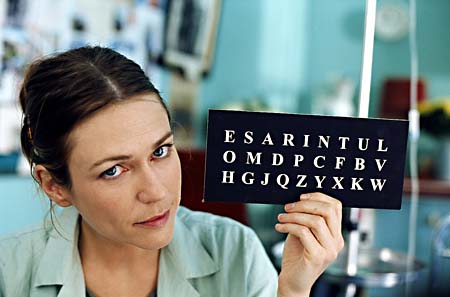

In 1995 at the age of 43, Elle France editor Jean-Dominique Bauby suffered a stroke that paralyzed his entire body, with the exception of his left eye. Using that eye to blink out his memoir, Bauby eloquently described the aspects of his interior world, from the psychological torment of being trapped inside his body to his imagined stories from lands he’d only visited in his mind.

Bauby’s story is astonishing, though (as is often/always the case), not reproduced with absolute faithfulness by the film. But it’s not a very cinematic story, at least on the face of it. And that’s where this film’s real genius surfaces, because it somehow manages to be incredibly cinematic. It will definitely appeal more to the “art-house crowdsters” out there, because it’s languid and artsy and nonlinear; a bit “stream-of-conscious-y” (again, fittingly). Also, subtitles. So, fast-paced and easily accessible, it is not. But lyrical and gorgeous and deeply moving? That, and in spades.

Part of this is surely the result of its cast subtlety-yet-powerful performances. Mathieu Amalric, who plays Bauby, was greatly heralded at the time of the film’s release. Yet his performance is almost imperceptible, by its very nature. So it was the supporting turns that really caught my attention. Emmanuelle Seigner is wonderful as the estranged mother of Bauby’s children. (The scene where she sits at his bedside, serving as the intermediary between her beloved “Jean-Do” and his current paramour — too terrified to visit in person — is brutal.) Marie-Josée Croze as the speech therapist who helps Bauby find his “voice” is fantastic. (That moment when Bauby confesses to her that he wishes to die and she breaks down? Spine-tingling.) Anne Consigny, his translator and scribe, provides us with an anchor point as the film increasingly blurs the lines between its narrator’s “locked-in” reality and his expansive, imagined worlds. And Max von Sydow as his father, struggling with his own failing health and isolation, is searingly, achingly sad. (Incredibly human, real, emotional stuff throughout. Yes, I teared up, time and again. And was glad of it.)

Part of this is surely the result of its cast subtlety-yet-powerful performances. Mathieu Amalric, who plays Bauby, was greatly heralded at the time of the film’s release. Yet his performance is almost imperceptible, by its very nature. So it was the supporting turns that really caught my attention. Emmanuelle Seigner is wonderful as the estranged mother of Bauby’s children. (The scene where she sits at his bedside, serving as the intermediary between her beloved “Jean-Do” and his current paramour — too terrified to visit in person — is brutal.) Marie-Josée Croze as the speech therapist who helps Bauby find his “voice” is fantastic. (That moment when Bauby confesses to her that he wishes to die and she breaks down? Spine-tingling.) Anne Consigny, his translator and scribe, provides us with an anchor point as the film increasingly blurs the lines between its narrator’s “locked-in” reality and his expansive, imagined worlds. And Max von Sydow as his father, struggling with his own failing health and isolation, is searingly, achingly sad. (Incredibly human, real, emotional stuff throughout. Yes, I teared up, time and again. And was glad of it.)

Don’t let the bleak synopsis scare you off, either. This is a deeply hopeful film about a man finding a way to connect with the outside world in the face of nearly insurmountable challenges. But it’s not the fact that he overcomes the seemingly impossible that is so moving. It’s that he refuses to succumb to the despair that would be a perfectly understandable result of his condition, instead turning the crushing blow he’s been dealt into the opportunity for an incredibly important internal transformation.

For me, though, the most memorable stuff was the countless little ways in which Schnabel made me feel — in an astonishingly, even disturbingly visceral way — like I was Bauby; that I, too, was “locked in.” It helps to be working with a genius like Janusz Kaminski, I’m sure, but the first 20 minutes of “First Person Perspective” were as mesmerizing as anything I’ve seen in the past few years, using a whole host of cinematic tools to incredible effect. Extreme close-ups, strange focus planes, framing that’s frustratingly off, and the fact that Bauby can talk but no one can hear him, all adding up to an extraordinary mood and effectiveness. And the gradual opening up-and-out as the film progresses is …hard to describe, really. It’s not particularly story/script-driven, but highly emotional, instinctive stuff. As you can see for yourself.

I decided to stop pitying myself. Other than my eye, two things aren’t paralyzed, my imagination and my memory.

Brief final notes: I don’t care for that trailer. It accurate, sort of. But it’s also all wrong. So if this recommendation doesn’t really strike your fancy based on that trailer, you might still give it a try. Also, this is most definitely not a film for kids. Troubling material, fleeting medical nudity, fleeting sexualized nudity, and a challenging story and style. Also, if you have trouble with eye-trauma (like I do), you might bail about 10 minutes in. Don’t, though. Keep going.

Attribution(s): All posters, publicity images, and movie stills are the property of Miramax and other respective production studios and distributors, and are intended for editorial use only.