It’s a little embarrassing, but the United States is one of only three nations that doesn’t mandate some form of paid maternity leave for women in the workforce. The causes for this are complex, connected as much with a set of historical causes as with any unique ideology – as we may see here.

From a pro-life standpoint it seems crucial that we rectify this. Whatever one thinks about women and the domestic space, our economy leaves many women with no choice but to enter the workforce. Thus the prospect of pregnancy can be terrifying not only for a poor single woman, but also for the married woman whose financial security is precarious from one week to the next, and for whom the possibility of radical frugality is impossible due to student loans, mortgage payments, car payments, etc (debt is, after all, the American way, and many of us were drafted into it).

Many jobs are hard to do while pregnant (try morning sickness when your job entails dumping fifty-pound boxes of rancid chicken meat into dumpsters. Try pregnancy brain when your job entails waddling to the board and spelling “onomatopoeia”). And even if you like your job, you might not keep it. Bosses with a mind towards “productivity” often find legal loopholes in order to terminate a pregnant woman’s employment. And then there’s that delightful “morality clause” that allows religious organizations to fire a woman who gets pregnant out of wedlock (structural sexism in a very overt form)

Then, what to do after the baby is born? Put a newborn infant in daycare? This is expensive, and often dangerous. Infants easily get sick in daycares. So then you have to stay home from work. Employers don’t like this. Most workplaces, and this includes religious workplaces, won’t let you take your baby to work.

If this is daunting for a financially secure married woman, imagine what it means for a single mother with children to provide for already.

In “The Demographics of Abortion: It’s Not What You Think” Amanda Marcotte writes:

“The most recent data suggests that the disparity has only gotten larger. Today, a full 42 percent of women having abortions live under the poverty line, and another 27 percent have incomes within 200 percent of the poverty line. Taken together, 69 percent of women who have abortions are economically disadvantaged” (http://prospect.org/article/demographics-abortion-its-not-what-you-think).

According to Guttmacher Institute findings, sixty percent of American women having an abortion already have a child, and over thirty percent already have two or more children. And “Women with family incomes below the federal poverty level ($18,530 for a family of three) account for more than 40% of all abortions. They also have one of the country’s highest abortion rates (52 per 1,000 women). In contrast, higher-income women (with family incomes at or above 200% of the poverty line) have a rate of nine abortions per 1,000, which is about half the national rate.”

(http://www.guttmacher.org/in-the-know/characteristics.html)

Are women choosing abortion to be free to pursue hedonistic pleasures? Are women choosing abortion because they don’t want children? These statistics suggest that, actually, women choose abortion because they feel they have no other choice. We do not live in a society that makes it easy to have a baby, unless one is already well-off. The rhetoric of poverty-shaming often emphasizes the size of a family or number of children, as though the children of a poor woman depending on public assistance are somehow less valuable.

In recent years, many pro-life feminists have come to focus on eliminating the demand for abortion, instead of the supply. This is probably the most effective approach at present, if our end goal is saving lives. It’s also possibly the more just approach – because, even if Republican leaders were capable of making good on their promises to eliminate abortion, the root evils that drive women to seek abortion would still remain. Abortions would still happen. The democratic leaders, on the other hand, may do better at caring for the person after birth, but seem ridiculously content to accept abortion as an easy panacea.

And perhaps this is because creating structures of support for pregnant women demands responsibility from those around them. And in America, with our emphasis on market productivity, individualism, and consequentialism-lite, it’s hard to get folks to agree to this. The mantras from business owners (including Christian business owners): it’s not the boss’s responsibility to repair the mistakes of others; she made bad decisions; it’s up to her to deal with the consequences; it’s her duty to do the right thing; it violates individual freedom to be coerced into helping her; if an employer wants to be generous that’s noble and charitable but not required.

I would like to suggest that if we are working towards a pro-life society it is, in fact, required. I would go so far as to suggest that parental leave should be given to fathers, as well, especially if we are going to maintain the idea that a father plays an important role in family life.

The difficulty, obviously, is that it might be difficult for a small business to pay for parental leave. And this is where I shall utter that dread word: socialism.

If you are still under the impression that socialism is verboten for Catholics, here and here are some basic accounts of what the hierarchy actually teaches.

Or take a nod at this statement from the bishops:

“There may be times when a Catholic who rejects a candidate’s unacceptable position even on policies promoting an intrinsically evil act may reasonably decide to vote for that candidate for other morally grave reasons. Voting in this way would be permissible only for truly grave moral reasons, not to advance narrow interests or partisan preferences or to ignore a fundamental moral evil.”

And here is a post suggesting that, actually, in this election our semi-socialist candidate might be our better option.

Personally, I avoid affiliation with most “isms”, but I do believe I have an obligation to stand in solidarity with those who are serious about correcting social problems. It’s not that I particularly trust the government, but so long as collective powers exist I think we should direct them towards doing the most good.

So, my own addition to these points:

- We need to consider whether we are obligated to vote on what a candidate believes (or claims to believe) – or whether we are obligated to vote on most likely outcomes. Is it helpful to have a political leader make the right statements about “right to life” if he or she initiates actions that lead to destruction of life?

- Many arguments in favor of Sanders have pointed out that, unlike most Republican candidates (and unlike Clinton) he is pro-life on all the other issues. But I’d like to take it a step further and suggest that, looking at politics in terms of outcomes, even if one votes only on opposition to abortion, Sanders’ policies might be the most viable. Given the statistics on who is having abortions, when, and why, it seems as though policies that provide greater financial and medical support for women and for families will be far more effective in decreasing abortion rates than will GOP promises about outlawing abortion.

- For Catholics with a more libertarian bent (and I was one once….still am on some issues) there is a concern that by placing the responsibility for providing safety nets in the hands of the government, we deprive individuals of the opportunity to give to charity. To which I answer: first of all, the poor will always be with us. There will always be opportunities to give to charity, and saying that we can’t because we’re taxed too heavily seems to me a cop-out. And as it stands, often individuals with no friends or family slip through the cracks. Or else the care for an individual ends up resting heavily on only a few people who really can’t afford it. Moreover, our obligation to care for the extremely poor sometimes is neglected, as we try to help out those teetering on the edge of poverty closest to us. Lastly, the emphasis on depriving the wealthy of their chance to act charitably wrongly deflects the conversation from the preferential option for the poor, focusing it on the first-world concerns of well-off people who want to feel good about their benevolence. Perhaps in an ideal world everyone would joyfully share with everyone else, freely, but the moral right of a woman to have food for her child can’t wait until we’ve created this ideal world (especially since we never will, original sin being a thing, and all).

Pax et bonum

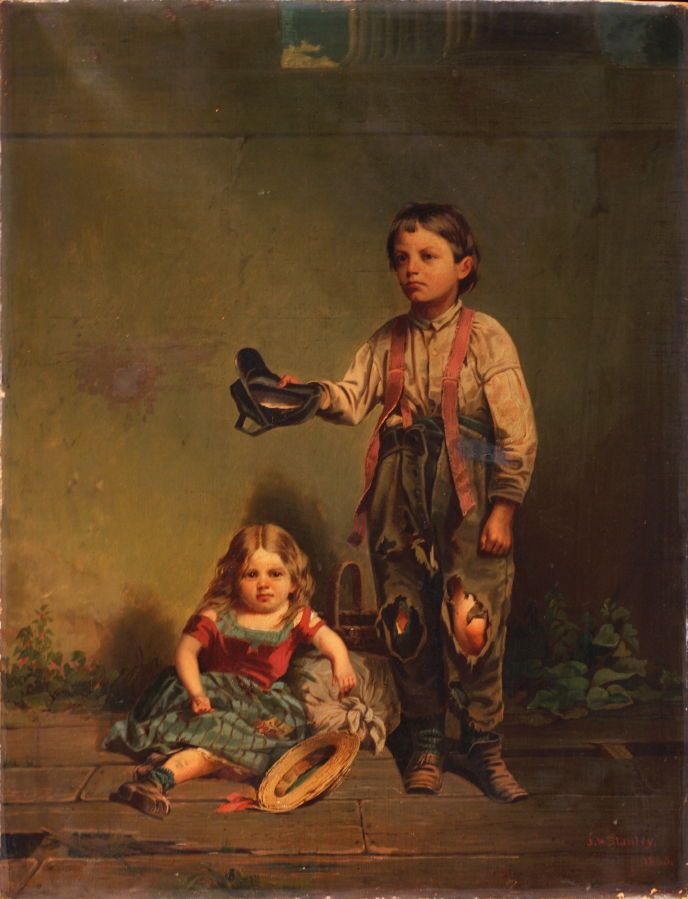

image credit: John Mix Stanley, Beggar Boy. US Public Domain, Wikipedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Mix_Stanley_-_Beggar_Boy.jpg