Umberto Eco, philosopher and story-teller, died yesterday at the age of 84, leaving me to chastise myself for doing exactly what I derided in yesterday’s post : mourning the death of a person because of the loss of production, in this case the production of works that rock my epistemological world. I guess my best tribute to him, then, will be to find how the world rocks on my own.

Or, perhaps, to find how it doesn’t.

When I was eighteen, I happened upon The Name of the Rose in a used bookstore, and immediately became obsessed. As a philosophy and Great Books student, I was thrilled to find a story which treated the pursuit of ancient wisdom not as an arcane curiosity for a few geeky weirdos, but as a matter of life and death. It appealed to my sense of having special knowledge, and I amused myself by imagining other readers who just didn’t get it the way I did, readers unaware of the politics of the early Franciscan order, or of the history of Aristotelian texts.

The irony of this is, I hope, not lost on you. First, because on any scale of “special knowledge” Eco himself is going to tower far beyond any sophomore philosophy student, and had I been wiser I would have been humbler, recognized my “special knowledge” as mere ordinary education. But, more importantly, because Eco was masterful at deconstructing the desire for gnosis, and I fell into the same trap that snared so many of his characters.

My favorite Eco novel is probably Baudolino, though I can never find anyone with whom to discuss it (gnosis again?) but right now let’s talk about Foucault’s Pendulum, a work so weighty with pedagogy that it should make even the cleverest undergrad feel her inadequacy. This is a novel that, just in passing, anticipates and derides the basic idiotic premise of The Da Vinci Code. Awesome, right?

The basic plot of Foucault’s Pendulum: three erudite friends amuse themselves by using computer programming and story-writing outlines to syncretize the world’s great conspiracy theories into a single super-conspiracy-theory. In so doing they inadvertently create an alternate history of the world, and become the prey of the leaders of secret societies desperate to possess their arcane knowledge (which, of course, is not knowledge at all, but fantasy).

At the end of Foucault’s Pendulum you will probably know a lot more than you knew before, about the Knights Templar, the Rosicrucians, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Candomble, and communism. You will also, if you are reading well, find yourself blessedly immunized against the fever for gnosis.

At one point in the novel, a character explains how she protects herself against sexual predators:

“When I asked if she wasn’t afraid of sexual maniacs, she told me her method. When a sexual maniac approached, threatening, she would take his arm and say, “Come on, let’s do it.” And he would go away, bewildered. If you’re a sexual maniac, you don’t want sex; you want the excitement of its theft, you want the victim’s resistance and despair. If sex is handed to you on a platter, here it is, go to it, naturally you’re not interested, otherwise what sort of sexual maniac would you be?”

I haven’t ever had the guts to use this technique (a kick in the crotch seems simpler) – but I see the parallel with desire for knowledge. It’s connected with mimetic desire. We want precisely what we can’t have. Electricity would probably seem like an arcane magic if it weren’t installed in every home. If everyone had a copy of the second book of Aristotle’s Poetics, no one would think it such a big deal. And in these cases we long for knowledge not with the purity of intellectual appetite, but with the desire for power. Thus even that most perfect of pleasures, the pleasure of learning, ends up corrupted.

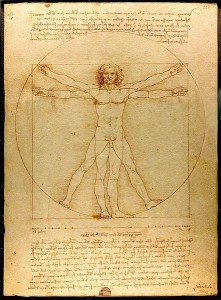

The appetite for secret knowledge leads us away from appreciating the simple realities that confront us. We no longer see the body as the body, but as a layer of palimpsests, something to be deconstructed by metonymy or human sacrifice, something to be distilled in strange Rosicrucian rituals or counted out via cabalistic number-codes. And oh, it is all so sexy. Uncovering things that don’t want to be uncovered…or do they?

It’s not enough to understand the history of the land one lives on, who farmed it, what was planted there, which corporations destroyed it. It’s not enough to understand how plants grow or birds fly. One becomes deeply discontented with any knowledge that isn’t special and exclusive. It’s not enough to observe the minute details of human interaction and disappointment and attempts and failures: we have to have conspiracy theories about treason and murder. An ideological enemy has to be made into a monster, because making a man into a monster requires secret knowledge.

And yes, the secret knowledge is all very stupid, but as long as you keep it secret no one will notice.

“They still want the Map. And when I tell Them that there is no Map, They will want it all the more.”

The longing for gnosis is a kind of nihilism, after all. It’s probably connected with the longing for a demagogue. The bored post-modern can’t appreciate the taste of a peach or understand that it’s worth it to study how fungus grows or jellyfish move. He’s sick of a world that he never even bothered to understand, and it amuses him to elect a lunatic who offers nothing but the promise of conflagration. This is stupid, too, and the bored post-modern embraces stupidity because it is ironic.

Read Foucault’s Pendulum. Then go take a walk and find a green hill to look at, so you can see what the narrator of the novel discovers too late.

*****************************************************************************************************************

“As a philosopher I am interested in truth. Since it is very difficult to decide what’s true or not I discovered that it’s easier to arrive at truth through the analysis of fakes” (Umberto Eco, Guardian interview)

Image credit: Leonardo da Vinci [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons