I’ve spent a lot of time, in the past few months, in conversation with abuse survivors.

It’s been painful to hear what they have to say, but my pain in hearing is nothing in comparison to the pain they carry with them – sometimes for most of their lives.

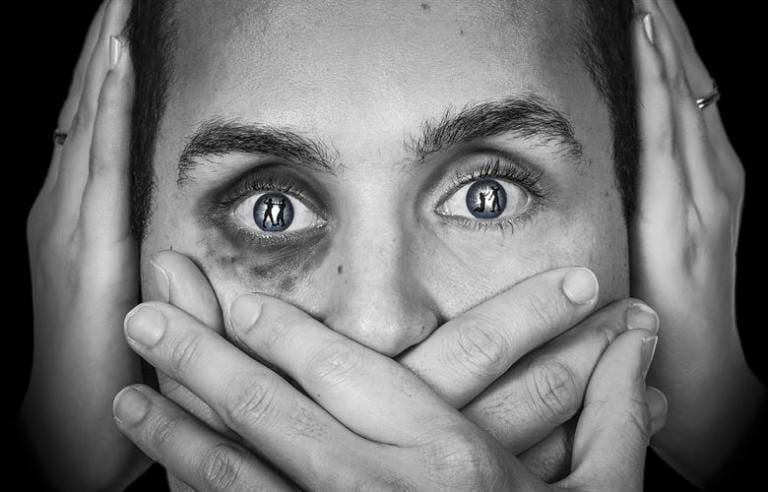

Turning away from these stories is not an option for me, uncomfortable though they may make me. Because in so many cases, the pain survivors carry is multiplied and exacerbated by the fact that over and over no one would listen. No one would believe them.

I’ve had a tiny taste of that frustration myself, when people refused to believe I was telling the truth about the abuse and toxicity I witnessed in a former workplace. Instead of listening, people over-wrote my story of injustice with a narrative that was more comfortable for them:

Maybe I was the problematic one?

I must have been causing drama.

I was probably overreacting.

It takes two to tango.

Anyway these problems are everywhere, so why the big fuss?

A few people just didn’t want to listen – didn’t want to “get involved” or have to take sides.

Revising cherished conceptions can be painful.

As I carried my frustration around with me, it occurred to me that I was getting an insight into the destructive mechanisms at work in the church’s abuse scandals. And the sad thing is that so often these mechanisms are born out of good intentions.

It’s especially difficult for people to believe stories of abuse and injustice when the stories require them to go back and revise a preconception about something or someone that they thought well of. This is true when it comes to the clergy abuse scandal: some people simply refuse to believe it of “a good and holy priest.” And it’s also true of domestic abuse: women are not heard because even their friends refuse to believe it about a man they think well of.

This inability to hear is also associated with a need to protect institutions. People don’t want to believe bad things about the institutional church to which they have given heartfelt allegiance their entire life, on which their identity is based. They don’t want to accept that Catholic institutions they’ve been trained to revere are not only just as bad as secular ones, but sometimes worse. They can’t accept that the institution of Catholic sacramental marriage might be a place for abuse so awful that a woman would need to flee.

This mechanism is at work even in the way women who speak out about the problems with NFP get shut down. We have an official, dominant narrative and we must not let these inconvenient outliers disrupt it.

In order to preserve the approved and cherished narrative, people will quickly shut down the stories of those who do not fit neatly into the mold.

It must have been your fault in some way

It sounds so implausible, you must be exaggerating.

If it was so bad, why didn’t you escape?

What did you do to provoke him?

You must not have been trying hard enough.

You must not have said “no” loudly enough.

Everyone has to bear their crosses, and marriage is a cross.

Bad theology, bad anthropology

If a person’s problem – whether it be the irritation of a failed fertility management system, or the absolute horror of traumatic, systemic abuse – requires us to revise the narratives with which we are comfortable, we often choose a cozy falsehood over a complex and demanding truth. One way we do this is in pretending that all stories are the same, all bodies are the same, all relationships can be fixed in the same way. If we failed where others succeeded – in escaping abuse, in making NFP work, in recovering from trauma – people need to believe that it’s due to some misstep on our part. Because otherwise they’d have to accept the terrifying reality that the good things in their lives are not all the result of their hard work and smart choices, but rather of chance – or, if you like, providence.

The Catholic tradition has always emphasized grace and gratitude, reminding us that what we have is not our own, that we should not preen ourselves on our successes. But this is very foreign to the contemporary American way, which emphasizes a weird mix of radical individualism with a mechanistic and reductive view of the person according to which everyone is made to fit the same template and every situation can be controlled.

Since I began listening – and, really, I began years ago, when students who had been abused or silenced began approaching me – I’ve had to revise an awful lot of my preconceptions. Sometimes this has been painful. But the pain is worth it, if we value truth and justice over comfortable illusions.

To all of those who are still unheard: I’m sorry for the pain you are experiencing.

There can sometimes be a burning need to make yourself heard, not just in general, but to particular people – to have them validate your story, instead of continuing to deny or ignore it. The disbelief or indifference of those you’d hoped you could trust may compound your sense of pain and isolation. And maybe sometimes those people will come around – or, maybe, they won’t, and you might have to step away from them, seek out those who are willing to journey with you. This may make them angry, because when you step away from them they can no longer shape your plot-lines to suit their comfort. It may make them sad, because they did truly care for you, but imperfectly, so long as they clung to an idol more.

And always remember: each person is unique and irreplaceable. Each of our stories is irreducibly our own. And no one else’s personal anecdote or institutional narrative can erase your reality.

image credit: Creator:Airman 1st Class Christopher Quail