A friend on social media posted today:

How are you?

Not a rhetorical question.

Be as honest as you feel comfortable.

I’m genuinely asking: how are you doing with everything?

It was a relief for me to see others answering “not so well.” It was a relief to have it acknowledged that not doing well is in fact a rational response to the current state of affairs.

The relentless pursuit of happiness was written into the founding of our nation’s culture. This is, from some angles, a good thing. It is good to pursue happiness when happiness, eudaimonia, has to do not only with a fleeting feeling but with the good life, the life of virtue and justice. Even the pursuit of good feeling, pure pleasure, is legitimate. I would rather live in a society that recognizes the validity of my desire to feel good than one that holds up suffering as a norm. And I have written before about the danger of fetishizing suffering, making it out to be a good when in fact it is evil.

Yet at the same time the drive to be happy, successful, upbeat is exhausting. The obsession with having an answer or solution means we churn out stupid answers and insufficient solutions, the kind of bland mantras that sell self-help books and inspirational manuals. Often the authors of these books and manuals end up coming to grief, mired in their own terrible advice. Or else they get lucky.

Our culture needs to give us space for saying that we do not know, that we haven’t found the solution yet, that we are working on it, that it is hard, that we may fail, that it is painful, and that this pain is not beautiful. We need to be given able to possess our grief.

Grief, I want to clarify, is distinct from suffering, especially the kind of suffering that is irrational, the suffering that we bear because something has been done to us. Grief, on the other hand, is an act. It is an act that is fundamental to life, precisely because suffering and death appear to be inextricably tangled with life. Failure to experience sorrow in the face of loss and privation is a failure of truth.

When one has experienced personal loss or pain, grief is necessary. To stave off the experience of sorrow is to cut off that aspect of one’s personality that was awakened to love and friendship. This is generally recognized. The value of collective mourning is recognized as well, when it comes to cataclysmic events to which we bear witness as a group. This is why we have set aside days appointed for the remembrance of certain great losses – such as loss of life in warfare.

Less generally recognized is the value of existential grief. This is not the same as personal grief, since it is not necessarily about a loss one has experienced directly. This year I mourned the death of my father. But I am also aware that two hundred thousand others died who should not have died, who could have, perhaps, been saved, had those in authority behaved responsibly. I mourn also for the refugee mothers separated from their children, their children incarcerated. I mourn for the families who have lost loved ones to state-sponsored violence. When I turn on the news I see homes battered by waves, in the Gulf, and homes devoured by fire on the west coast. And all of this unfolds before me with the garishness of an action movie, and we are expected simply to take it in, note it, carry on. There has been no national mourning for our dead. There is no collective ritual of sorrow for the loss of our eco-systems.

Our existential sorrow is compounded by the fact that so much loss goes unacknowledged. By the fact that we live in a political system calculated to make sure these losses go unacknowledged, for the sake of profit and power.

“It is what it is,” said Donald Trump, of the victims of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is our national shrug, the same shrug with which we routinely greet the news of yet another mass shooting, or the spectacle of homelessness. We have fumbled our way through this pandemic in search of the next distraction, washing our hands of responsibility.

That power in my soul that has rejoiced in times of triumph is the same that mourns in times of loss. I don’t believe that sorrowing is the only thing we can do, but it is a thing that we should do. We can only hope that this is not practice for a time when it is all we have left.

No man is an island, John Donne wrote. Ask not for whom the bell tolls. It tolls for you.

The loss of lives, destruction of communities, and desecration of eco-systems is our loss. All of ours. Even if some of us feel it less poignantly – or not at all. Some may even be complicit in it. But none of us are cut off from it.

Persons in vulnerable and oppressed communities often point out that, however “tired” the rest of us may be, of hearing about grim political realities, many of us can at least take a break from thinking about them. I can take a break from thinking about racial injustice or police brutality, when it starts making me angry to the point of exhaustion. Victims of these evils can not. Those who are directly affected by climate change can not opt out of worrying about it, as they flee fires or flooding.

Those of us who can still afford to opt out are fortunate. We may not be fortunate always. And no matter how hard we work to fight for racial justice, climate justice, economic justice – there is no guarantee that we will win. Hope, yes. Assurance, no.

The future is not necessarily bright. Things are not necessarily going to get better. Climate change, the disruptions of our eco-systems, and the normalization of extremist authoritarian regimes may truly be beyond our control. They may in fact be the common way of things, and what we think of as “normal” merely a blip of good luck we happened to have – for a time. If this is the case, the right response is not a shrug but a lament. We can not draw a line between the personal and the political, leaving the bad feelings over on the political arena, beyond, while keeping cheery and upbeat in some imaginary cordoned-off personal zone where none of that stuff really affects us. It is affecting hundreds of thousands now. And there is no rule that says it won’t affect me. There is no talisman for my singular protection.

I need to have my sorrow. I need to have my anger. People tell us that sorrow and anger are unproductive , and I don’t believe it. I think this is a lie that serves the narrative that no systemic change is needed, or that we should simply accept injustice. But supposing it is not a lie? Even if anger and sorrow produce nothing, accomplish nothing, they may still be necessary. They may be what keep us human.

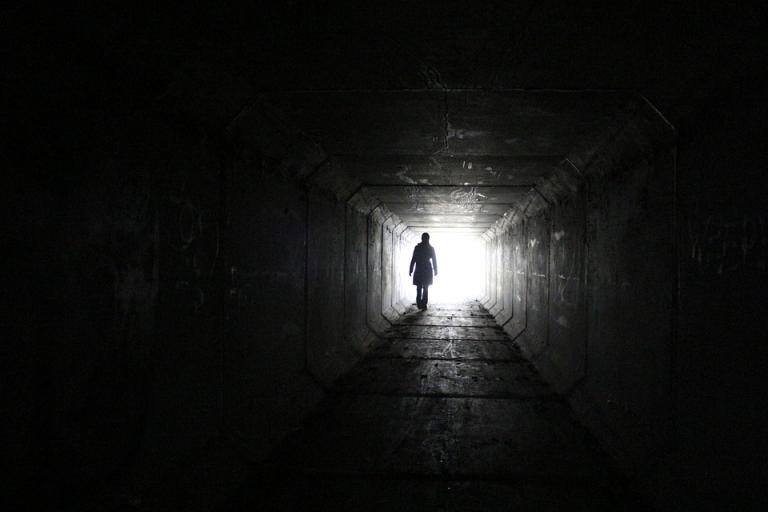

image credit: pixabay-photos-tunnel-silhouette-mysterious-899053.jpg