“Do we really need another one of these?”

“Do we really need another one of these?”

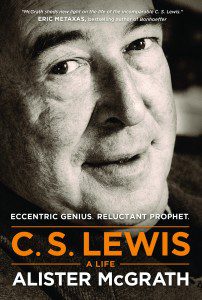

When I saw that a new biography on C.S. Lewis was coming out this spring, I sighed over what I saw as yet another attempt to introduce Lewis to a new generation and those new to the faith and, therefore, to him. Make no mistake, I’m a C.S. Lewis guy. So are a lot of other people. End of the century polls from sources like Christianity Today listed Lewis’s Mere Christianity as the most important Christian book of the 20th Century. Other polls did the same, including The Screwtape Letters and The Chronicles of Narnia as well. (My favorite? The Great Divorce.) Multiple biographies already exist, written by people who knew Lewis, and a movie, Shadowlands, portraying the marriage of Lewis (starring Anthony Hopkins) and Joy Davidson holds a special place in the hearts of many Lewis followers.

Whether we need another one or not, I’m glad we have this one. One thing that drew me was the author. As many read this new biography out of interest in C.S. Lewis, they will meet Alister McGrath. While many Christians know of N.T. Wright, an amazingly prolific British author, Alister McGrath is known largely just on the other side of the Atlantic. How many people do we know who have earned two doctorates from Oxford University – one in molecular biophysics and one in theology? He writes across a broad field including theology, apologetics, history, science and he writes a lot. Along with this book, he is co-releasing a book on the intellectual world of C.S. Lewis. Okay, he’s smarter than a tree full of owls on steroids. But he writes in ways that are a pleasure to read. For example, he writes of Lewis’s father sending him off to private school in England immediately following the death of his mother (Lewis grew up in Belfast, Northern Ireland) and its devastating effect. “An emotionally unintelligent father bade his emotionally neglected sons an emotionally inadequate farewell.”

C.S. Lewis, A Life gives both a good introduction to the Lewis novice and more than a few nuggets to the Lewisphiles. One main benefit of McGrath never personally knowing Lewis lies in that the Lewis we meet here is a “warts-and-all” portrayal. When biographies get penned by friends and admirers, this almost always colors the story no matter how hard the author tries to avoid it. McGrath researches points that will challenge Lewis “geeks” – things such as the timing of his conversion to Christianity and the publication order of the Narnia books. He also says that Shadowlands seriously over-romanticized Lewis’ marriage from the real one described here. Not that they didn’t love each other but… you’ll have to read it for yourself. He also points out that God drew a number of significant literary figures to Himself at about the same time as Lewis (although he had none of their renown at the time) including G.K. Chesterton, Graham Green, Evelyn Waugh and T.S. Eliot. All these were drawn to faith through and because of their literary interests. Their love of literature wasn’t incidental to conversion; it was foundational. In Surprised by Joy, Lewis wryly notes, “A young man who wishes to remain a sound Atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. Traps are everywhere.”

The pre-Christian Lewis gets a thorough look. His childhood solitudes with books that cultivated his imagination from the youngest age, his attempts to avoid military conscription in World War I, subsequent service in Europe which he never talked much about and return to academic life all come under the microscope. His interesting relationship with Mrs. Moore, mother of a friend killed in France, gets more than a look with conclusions that contradict earlier bios of Lewis. The Oxford and Cambridge don years open up beautifully under McGrath’s guidance simply because he’s been there and not much has changed since Lewis’ day. Utterly unkempt in appearance, Lewis enveloped his office during tutorials with huge clouds of smoke and used his carpet as an ash tray. He brilliantly lectured without notes and wrote the first draft of Pilgrim’s Regress in just two weeks. All this notwithstanding, for most his career at both schools, Lewis never held the respect of many of his academic colleagues. Professional jealousy aside, they viewed his writing as merely popular and not very scholarly. He also exercised bad judgment involving internal politics which would cost Lewis three promotions.

Lewis oddly related to his friends. Although he and J.R.R. Tolkien (Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit) became not only fast friends and the driving force behind the famous discussion group, the Inklings, they drifted apart during the WW II years as Charles Williams became Lewis’s primary confidante. The relationship never warmed up again even though Lewis dedicated The Screwtape Letters to Tolkien. Tolkien thought it less than serious literature and knew that Lewis himself wasn’t all that keen on it. Yet they still maintained deep professional respect for each other that would be demonstrated repeatedly through the last years of their lives. Women were never part of the Inklings even though some would include Dorothy Sayers. McGrath documents this as untrue. But behind the scenes, Lewis actively supported and encouraged many female writers and actually paid stipends to some out of his royalty money so they could continue their work.

McGrath caps his good work with two especially strong points. He lays out well the major shift in Lewis’s thinking from his early Christian days to the later years. Renowned as the Christian apologist defending the faith in works like Mere Christianity and Miracles, as well as the famous BBC wartime broadcasts, Lewis declined a prestigious offer from Carl F. H. Henry of the young magazine flagship of American evangelicalism, Christianity Today. Lewis moved on in his later years from intellectually defending Christianity to describing its wonder, attraction and allure for Christians and those on the brink of becoming one. He played to the yearning inside every human heart for something beyond, something more.

McGrath also lays out the unexpected renaissance of Lewis after his death, especially in America in the late sixties and early seventies. In his last years, Lewis thought himself to be sliding into eclipse and those (mostly in academia) who disparaged his work consigned his writing to the files of being a cultural relic – good for his time but the times have moved on. The resurgence turning his name and works into both an icon and a canon would have caught him very much by surprise.

Alister McGrath captures C.S. Lewis with both respect and affection. Both Lewis “geeks” and those captured by Mere Christianity or Narnia meeting him for the first time will be well served by C.S. Lewis, A Life. It’s to be chewed slowly and savored. Even Lewis’s clay seen in its pages makes for a canvas where the beauty of One can be seen of Whom the magnificent Aslan is only a snapshot.

For more conversation on C.S. Lewis, A Life, visit the Patheos Book Club here.

David Swartz pastors Bethel Baptist Church in Roseville, Michigan. He thinks that jazz is sacred music, that books are better company than most people, and that university towns rock. He blogs at geezeronthequad.com.

David Swartz pastors Bethel Baptist Church in Roseville, Michigan. He thinks that jazz is sacred music, that books are better company than most people, and that university towns rock. He blogs at geezeronthequad.com.