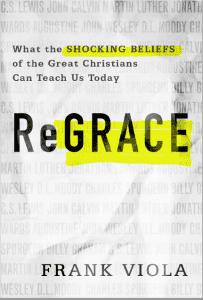

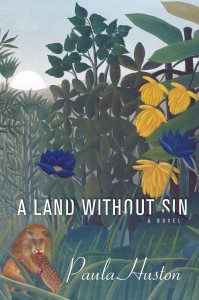

Popular Catholic author and professor Paula Huston’s new novel comes out this month, A Land Without Sin. Set in the jungles of southern Mexico in the early 90s, the book is described as a modern-day journey into the heart of darkness, in which a sister goes searching for her lost brother, who happens to be a priest, after a mysterious disappearance. (Visit the Patheos Book Club for more about this book.)

Popular Catholic author and professor Paula Huston’s new novel comes out this month, A Land Without Sin. Set in the jungles of southern Mexico in the early 90s, the book is described as a modern-day journey into the heart of darkness, in which a sister goes searching for her lost brother, who happens to be a priest, after a mysterious disappearance. (Visit the Patheos Book Club for more about this book.)

Here, Huston talks with Caitlin MacKenzie of Slant Books about the inspiration for her story, how Catholicism plays into the narrative, the books and authors that inspire her, and her own writing process.

A Land Without Sin is set in the Lacandon jungles of southern Mexico in the early 90s during political unrest. What inspired you to write a novel set in such a time and place?

I spent the summer of 1969 in a mountain village in Honduras, where I was part of a volunteer inoculation program called Amigos de las Americas. I was all of seventeen, and it was my first time out of the country. While I was there, war broke out between Honduras and El Salvador, and since we were only fifty miles from the border between the two countries, we had refugees coming through our village. This was my first taste of how radically even a relatively brief, small-scale war like the so-called Soccer War of 1969 can alter people’s lives.

I spent the summer of 1969 in a mountain village in Honduras, where I was part of a volunteer inoculation program called Amigos de las Americas. I was all of seventeen, and it was my first time out of the country. While I was there, war broke out between Honduras and El Salvador, and since we were only fifty miles from the border between the two countries, we had refugees coming through our village. This was my first taste of how radically even a relatively brief, small-scale war like the so-called Soccer War of 1969 can alter people’s lives.

Then, during the 1993 Christmas season, my husband and I traveled with backpacks from Palenque in Southern Mexico to Tikal, Guatemala, camping along the way at famous Maya sites. We spent one long day traveling through the Lacandon jungle in the back of a second class bus. Toward evening, we found ourselves being passed by truckload after truckload of soldiers. Soon afterward, we were stopped, boarded, and searched at gunpoint. A day later, on New Year’s Eve, the Zapatista Revolution broke out. Like most American tourists, I knew almost nothing about Mexican history or politics, but from then on I became intrigued.

Eva Kovic, the main character, is definitely not your typical protagonist. How would you describe her?

Eva is young–only thirty-four–but extremely tough, the exact opposite of a confirmed coward like me, which is why I cannot help but admire her. As a photojournalist who has, by choice, spent her entire professional life chronicling the devastation of war, she is almost entirely hardened against emotional pain. Yet some part of her knows she is becoming a monster. For example, she is repulsed by weakness–not outraged on behalf of the weak, but actually made nauseous by the sight of them–and she’s honest enough to admit to herself there’s something off about that. The only person she has ever truly cared about is her brother, the vanished priest, though she’s not remotely in tune with what makes him tick. In fact, his religious idealism fills her with weary disgust. When it comes to physical danger, she is monumentally self-confident and adept, yet ask her to take an emotional risk and she’s out of there. In a lot of ways, she’s your classic action movie hero: brave, loyal, and cunning. But this familiar-sounding role is usually filled by some Bruce Willis type, not a quiet, slender woman with an artist’s eye for beauty.

The importance and complexity of family is a major theme weaving through the narrative. How did this become such an integral part of the story?

Amazingly (at least from my perspective as the author, who is often the last to see where the real story lines lie), this aspect of the book did not come into its own until after I’d written the first draft. I was asked by Slant editor Gregory Wolfe to develop a back-story that would make sense of cynical Eva’s devotion to her priest brother. After all, his manner of life and beliefs are not simply the antithesis of her own but actually offend her. How could two people so unalike find any sort of common ground, much less deep mutual love?

At first I was stumped. Then I realized they had to have shared some major experience, something so life-shaping and bizarre that they were the only people in each other’s worlds who understood. Whatever this thing was, it sent them on exactly opposite paths. And the only crucible strong enough to accomplish all this is of course family. There had to be a family story that accounted for their otherwise implausible comradeship. But there are already too many plots out there that turn on repressed memories of childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse. In our time, this device has become almost a cliche. I wanted to find a story that somehow transcended the individual, psychological experience–that turned instead on what happens to families when they get caught up in historical cross-currents such as war over which they have little or no control. These are the great events that reveal character, that unmask virtue or vice. As children, Eva and Stefan were haunted by dark experiences they had not personally lived through–experiences they could not possibly comprehend. Their self-protective response to this ever-present, malign, but invisible force in their lives was to love and care for one another with fierce loyalty.

The characters who populate A Land Without Sin seem to shuck their stereotypes: a wildly independent and emotionally distant protagonist; a theologically struggling priest-activist; a young, insecure guerrilla soldier. What attracts you to such complex and three-dimensional characters?

I supposed the best answer here is that I’ve always been fascinated by the mystery of the human person–the depths that, even in those closest to us, we can never plumb. I’m equally amazed by the mystery we are to ourselves. Who is that person in the mirror looking back at me? Given the right set of circumstances, any of us can be stripped in a moment of our hard-won social identities, our precious reputations–our sense of who we are. I’m interested in these moments of crisis, these existential reckonings that must occur at some point in every one of our lives. For these are the moments that either drive us to faith or send us fleeing in the opposite direction.

Another answer to your question would be that from earliest childhood, I’ve been an avid reader. And I learned early on that the novels I remembered were not so much plot-driven as they were people-driven. The really good ones were about characters I simply could not forget–characters I thought about, worried about, even prayed about, long after I was done with the book. So it was natural for me to focus here on character development rather than plot construction, to put these idiosyncratic people together and see what evolved from their interaction. Aside from the original situation (brother disappears, sister goes in search of him) the relationships between unlike characters who are almost incapable of understanding each other, along with the historical episode involving the Zapatistas, provide the conflicts around which the plot grows.

How is Catholicism important to the narrative?

When Mike and I went on that long-ago Maya trek through the jungles of southern Mexico and Guatemala, I was just starting to think about a life of faith after nearly twenty years of considering myself an atheist. Though I’d been raised a Christian, I repudiated all of that at seventeen, shortly after my revelatory Honduras stint and my brush with the evils of war. How could a good God, I asked anyone who would listen, allow so much suffering? Obviously, if he did exist yet let all this trouble happen, he could not be good. But given my upbringing in the church, the idea of a nasty or incompetent God made no sense to me. It was far easier to decide that he was simply a comforting myth, one I could now quietly let go of, which is what I did for a couple of decades.

It was a philosophy professor and his devoutly Catholic wife who re-opened the door of serious religion for me. And that door led to my first experience of the Mass. At the time of our trip to Central America, I was still “in training” as a neophyte Catholic, still enthralled with this new world I’d entered–still pretty idealistic, in other words. I didn’t yet know a lot about this adopted religion of mine. Now, twenty years later, I see Catholicism quite differently. Though if anything I love it more than I did back then, I’m also much more aware that every religious practice has its peculiar temptations and inbuilt pitfalls and the Catholic church is no exception. It lends itself, for one thing, to what some have called “church idolatry”–a worship of the institution and its incredibly long, rich, and often glorious history. It lends itself to defensiveness and a tendency to rationalize away the not-so-glorious times. And it lends itself to becoming a fortress for those who crave a strong moral and spiritual security system, the reassurance of authority.

The Church in Central America has certainly wrestled with all of these temptations. On the other hand, Catholicism is incredibly blessed by its “cloud of witnesses,” the saints and martyrs and anonymous practitioners of the faith who have successfully navigated these deadly shoals and gone on to become living testimonies to the power of Christ in an individual human life. And I wanted to show these contradictory facets of Catholicism–just as I wanted to show the complex and sometime self-contradictory facets of individual characters in the book.

What authors and books have been a guide and inspiration for you, both generally but also specifically for A Land Without Sin?

So many, that trying to answer this question in any depth feels overwhelming! As I said earlier, I’ve been an inveterate reader since I was old enough to read. But here are a few titles, beginning with the most obvious: Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and For Whom the Bell Tolls, Marilyn Robinson’s Gilead, Ron Hansen’s Atticus, the poetry of Carolyn Forche.

But then there were the works of culturally influential non-novelists, many of whom have influenced me as much or more as the great literary writers: Plato’s Republic, Iris Murdoch’s Existentialists and Mystics, Charles Taylor’s Sources of the Self, Douglas Burton-Christie’s The Word in the Desert, Hans Boersma’s Heavenly Participation. I could not have written this book at all without Linda Schele’s A Forest of Kings and Rene Girard’s I Saw Satan Fall Like Lightning.

Can you talk a bit about the process of writing A Land Without Sin? How did it come together for you?

I wrote a first draft of this novel nearly eighteen years ago under contract to Random House. But it’s clear that I wasn’t ready to write it yet. I was still too close in time to the personal experiences that precipitated the project, still too new a Catholic to be able to make any sense of the religious cross-currents surging through Central America, and still too busy working out my own theology and spirituality to do justice to a character like Stefan the anguished priest. I submitted that draft in 1997 and they did what any self-respecting publisher would do: they told me it would take far too much editorial work to make it jell and that I should forgot about it and move on to something new. So I stuck it in a box and put it on a shelf and really DID forget about it.

Last summer, Gregory Wolfe, longtime editor of Image: a Journal of Art and Religion, contracted with the publisher Wipf and Stock to create a new literary imprint called Slant. Their goal was to bring out five novels–books that would appeal to a general, fiction-loving audience–in the next few years. I have known Greg for some time and have published both short fiction and essays in Image. Shortly after he began working on the project, he emailed me and asked if I had “any old novels lying around.” Much to my delight, I could tell him I actually did. He asked to see the manuscript, I sent it to him, and he saw enough merit in this early draft that he rolled up his editorial sleeves and went to work. The questions that came out of his careful reading spurred me into an almost total rewrite. It’s a whole different book now. And I’m so very grateful to have had a second chance with it–even more, to finally see it in print.

How did your own life and experience inspire the characters and world of your writing?

Before we got married, my husband spent a few years teaching in international schools, getting to know families who put travel at the center of their lives. He was determined that our four kids would grow up with a wider view of the world than most Americans tend to get. As teachers, we had summers off, and we took full advantage of that time, dragging our family to as many places as we could go. But our budget was strictly limited, so we had to travel as cheaply as possible, mostly camping and backpacking or staying in hostels along the way. We also hosted a number of exchange students while our children were growing up, in addition to housing kids from inner city L.A. and staff members from a agricultural non-profit working in the poorest places in the world.

In 1996 Mike took five American high school students to Kazakhstan, and six months later, we hosted a visiting team from Central Asia. In 1998 I was fortunate enough to receive a faculty study grant from my university that allowed me to spend two months making a solo trip around the world to seven countries I’d never been, including Kazakhstan, Nepal and India. Many of my intuitions about the shaping influences on Stefan-the-priest came from my time in those countries. Finally, Eva and Stefan are of my own generation, and that was a great help in going back to the early 90’s for this story. It did not feel like “history” to me but instead, in some strange way, the story of a whole era, my own era.

You are a teacher and have been for many years. How does teaching speak into your writing, and vice versa?

Teaching forces me to articulate what I’ve learned after hours and days and years of wrestling with my own fiction and creative nonfiction. I think this is the most valuable gift to the writer that comes from being a teacher–having to really assess what it is you’ve learned, what you know, and what is still a mystery to you in your own creative life. More, the writing-teacher/writing-student relationship can be a very intimate one. For example, nowadays I teach graduate writing students who are focusing on creative nonfiction, particularly memoir. This means they are delving into the deepest (and sometimes most secret) places in their lives. Thus, my role as mentor sometimes includes being an informal kind of confessor. I find that my students are on my mind a lot in that regard. I think about them, worry about them, and pray for them. And I’m very aware that, like it or not, I am in some way a role model for them, which means they are also a spiritual prod for me. I feel obligated to live up to their respect.

What do you teach your own students about the writing process? What advice do you give them when they tell you they want to be a novelist, too?

I tell them that writing is the work of a lifetime, that they will exercise very little control over the outcome of all their efforts, and that if they do not love what they are doing so much they are willing to keep struggling through disappointment, self-doubt, guilt, frustration, exhaustion, anger at being criticized unfairly, and plain old dry spells, no matter what happens on the publication front, then they should give it up as soon as possible. But I also tell them that being a writer has blessed me in a myriad of ways: with beautiful friendships, with an excuse for constant study, with the adventure of stretching my mind to its very limits, with the joy of seeing a difficult project to its completion and holding, once again, a new book in my hands. I tell them there is nothing like it, and that I sincerely hope they will someday have those experiences too.