As a parent dedicated to mimetic theory, I know that the stories we tell our children pattern them in certain ways. Children have a remarkable capacity to learn not only reading, writing, and arithmetic, but also how to relate to others. Stories are particularly influential tools that teach children how to do just that. Of course, their learning potential can be patterned in relating to others in violent ways or in nonviolent and loving ways. And like so many parents who want to foster a strong sense of compassion in their children, especially compassion for their enemies, I struggle to find children’s books that tell compelling stories about compassion and reconciliation.

Mythical Stories and the Eternal Return

Children’s stories typically follow the same pattern as every other story. There’s a conflict. The conflict leads to the formation of good guys and bad guys. The good guys work together and, after dramatically losing to the bad guys on multiple occasions, end up winning the day. The bad guys are either killed or expelled and peace is restored.

If you read ancient myths, you will discover that the same story of violence has been told since the beginning of human culture. Human history has seen an eternal return to violence and wars where good battles evil in the hopes to restore peace. And then we mythologize our violence through heroic stories of “good versus evil” that we tell to our children. But achieving peace through violent means never leads to lasting peace. If there’s one thing we should learn about the eternal return to violence in mythical stories, it’s that violence leads to more violence.

But what if we told a different story to our children? What if we told stories about conflict that didn’t end up with killing or expelling the bad guys, but rather ended with relationships being transformed and reconciled? Maybe our children would be patterned in a way that seeks compassion for and reconciliation with our enemies.

Mickey’s Alternative

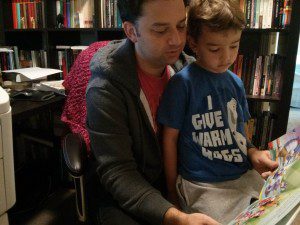

Yesterday, my second child brought home a book called Mickey Mouse Clubhouse: Super Adventures! As I began reading it to him, I couldn’t help but feel a twinge of parental angst as the story followed the same violent pattern as nearly every other story. Mickey and his friends turn into superheroes and unite to save the day from the evil villain Megamort, who wants to steal Mickey’s clubhouse by shrinking it with his shrink ray.

Yesterday, my second child brought home a book called Mickey Mouse Clubhouse: Super Adventures! As I began reading it to him, I couldn’t help but feel a twinge of parental angst as the story followed the same violent pattern as nearly every other story. Mickey and his friends turn into superheroes and unite to save the day from the evil villain Megamort, who wants to steal Mickey’s clubhouse by shrinking it with his shrink ray.

Oh the drama!

Of course, in the end Mickey and his team of superhero good guys win the day. But as Megamort attempts to make his escape, his plane springs a leak and zooms out of control. That’s when the ancient script of violence is flipped on its head and a new script of compassion and reconciliation emerges:

“Megamort needs our help!” shouts Mickey.

“But he’s a villain,” says Goofy.

“He still needs saving,” says Mickey.

Despite Goofy’s objection, Mickey and his friends safely bring the plane down and Megamort is transformed by their act of compassion.

“After all I did, I can’t believe you rescued me,” he says. “Thank you.”

“You’re welcome, Mr. Megamort,” says Goofy.

“I’m really Mortimer Mouse,” Megamort reveals. “I’m your new neighbor…I thought that if I took what you had, I’d be happy.”

“The Clubhouse is all about having friends,” says Mickey.

“That’s just it,” Mortimer admits. “I don’t have any friends.”

“You do now,” says Goofy.

This children’s story is revelatory for two reasons. First, the main principle of mimetic theory claims that we “desire according to the desire of another.” In other words, we really do try to “keep up with the Jones’.” As with Mortimer Mouse, we tend to think that if just had what our neighbors have that we would then be happy. But as this story clearly shows, the mimetic aspect of desire more often leads to conflict and resentment than to happiness. That’s why the 10th Commandment warns us against coveting our neighbors stuff – it knows that our natural inclination is to desire according to the desires of another! Of course, underneath it all, it’s never really about our neighbor’s stuff. Like Mortimer, what we really desire is friendship, love, and acceptance. That’s why the Bible says, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.”

The second aspect of the story that’s revelatory is that the conflict ensuing from “desiring according to the desires of another” often leads to the eternal return of conflict and violence, but it doesn’t have to. We aren’t enslaved to violence. We do have options. For example, Goofy suggests that Megamort should suffer the deathly consequences of his evil actions when he protests rescuing him from his demise by stating, “But he’s a villain.” Fortunately, Mickey provides a refreshing alternative of compassion by saving the villain.

Mickey models an alternative desire to the desire of mythical violence. It’s a desire that transforms us from wanting to kill or exclude our enemies to wanting to bless them and to reconcile with them. It’s the same alternative that we see developing in the Judeo-Christians Story. From Abraham and Sarah, who are called by God to be a blessing to “all the families of the earth,” to Jesus who forgives his enemies who crucified him and who reconciles “the world to himself, [by] not counting their sins against them,” we see that God sends us on a mission of blessing and reconciliation with everyone, but especially with those we call our enemies.

I’m glad to tell that divine story of reconciliation to my children wherever I can find it, even when it comes from Mickey Mouse.