Cultural diversity makes our world interesting, doesn’t it? Our lives would be so impoverished if we were not being exposed to that wonderful variety of language, food, clothing styles, and spiritual practices of cultures different than our own. Yoga and tai chi, bok choy and basmati rice, Oy vey and “hasta luego, baby”, Little Italys, Chinatowns, Irish folk dance and African music – the list of cultural cross-pollination is endless and we are the richer for it, culturally and personally.

Cultural diversity makes our world interesting, doesn’t it? Our lives would be so impoverished if we were not being exposed to that wonderful variety of language, food, clothing styles, and spiritual practices of cultures different than our own. Yoga and tai chi, bok choy and basmati rice, Oy vey and “hasta luego, baby”, Little Italys, Chinatowns, Irish folk dance and African music – the list of cultural cross-pollination is endless and we are the richer for it, culturally and personally.

Truth be told, our cultures are changed by our interactions with one another, which is the natural state of things. There does not exist any pure past in which our cultures developed in isolation without outside influences. Human beings are explorers, travelers, endlessly curious and unafraid to try new things. We appropriate one another’s cultures without a second thought. It is our modus operandi. In the case of my own Italian heritage, the food I so love is the result of influences from Asia and Africa and the poetic, flowery language of Dante developed in contact with Arabic. Who knew, right?

Hands Off My Story!

A scandal has recently erupted in the art world over “cultural appropriation”. What is wrong with artists borrowing from other cultures? As far as I can tell, it goes wrong when an artist of a dominant culture takes the stories of marginalized or oppressed minorities as his subject matter. For example, it could be cultural appropriation when a white writer tells a story with an African-American protagonist. “Appropriation suggests theft, a process analogous to the seizure of land or artifacts”, writes Kenan Malik in the New York Times.

Some in the art world have gotten in hot water recently for daring to defend cultural appropriation. Malik recounts the case of an editor of a Canadian magazine who lost his job for defending the rights of white authors to create characters of minority or indigenous backgrounds. Another editor lost his job for supporting the first guy. Last year a novelist defending cultural appropriation created a scandal at the Brisbane Writers Festival and this year the storm has engulfed two artists. Dana Schutz, a white painter, has been castigated for her painting of the mutilated corpse of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old African American murdered by two white men in Mississippi in 1955. Some have called for the painting to be destroyed. In another case, according to Malik, “sculptor Sam Durant dismantled his own piece ‘Scaffold,’ honoring 38 Native Americans executed in 1862 in Minneapolis, after protests from activists that he was appropriating their history.”

The Lie of Oppression

What is going on here? Are white artists being unfairly censored by overly zealous activists? Or is this a serious issue in which oppression is appearing in a new, albeit artistic, guise? This is tricky territory, of course, because artists are just like you and me – we are immersed in a complex matrix of cultural influences and sorting out who has the rights to tell which story can be a thorny problem. But hearing your story told by a member of a group that has oppressed you can trigger a sense that the oppression is happening all over again.

You see, the most effective way to oppress a people is to deny them a voice and the power to construct their own narratives of what is happening to them. Oppressors often excuse themselves with false stories about the intelligence, capabilities, and even the humanity of the cultures they oppress. Only the marginalized other has access to the truth that the self-serving narratives of their oppressors are lies. When a culture that has oppressed others refuses to change its story despite hearing the truth, they once again abuse and traumatize victims.

It’s Not Your Story or My Story – It’s Our Story

A wonderful example of a culture changing its narrative comes from Australia. When I visited last summer I was surprised by the inclusion of a welcome from a member of the local indigenous people at the events I attended, including a performance at the Sydney Opera House. Was it cultural appropriation or a heartfelt gesture of repentance? I thought the latter, but the final word belongs to the victims.

The problem with all this is that whether we are oppressing or repenting we are in relationship with victims. There’s no way around that – we can be honest or in denial, we can be erasing or honoring someone’s part in the story, but anytime we get near to the space of victims we will find it to be charged with emotion and drenched in violence. We can build our identities, as good and truthful people, by excluding and silencing victims and denying our violence. Or we can rebuild our identities as repentant victimizers by allowing our victims’ stories to reshape our own.

To frame the discussion as one of cultural appropriation is to miss the point. What we are talking about is not who has the right to tell the story, but whether liars can ever learn to tell the truth about violence. Truth is a relationship. So is violence. When oppressors portray the place of suffering as empty and silent, then the stories we tell, the paintings we paint and the sculptures we create deny our violence – we are liars. But when we fill the place of suffering with the anguish, pain and grief of our victims, we have begun to tell a more true story about ourselves, our violence and the victim suffering we have long ignored or denied.

Learning to Tell a True Story

Emmitt Till’s mother urged the publication of photos of her son’s body. Why? Because Mrs. Till had faith in white America, perhaps unjustified, that we could learn to tell the truth about the violence perpetrated by a racist culture that is deaf, dumb and blind to African-American victims. I think she hoped that the story of the goodness of a culture of segregation and racist violence would collapse in the face of the truth graphically illustrated by her son’s murdered body.

When white artists and reporters make well-meaning efforts to be more truthful, we must not be surprised if those efforts are greeted with mistrust and outrage, such as has greeted Schutz and Durant. Because just as we have built an identity by excluding our victim’s story, our victims have built an identity by telling a story about us. That we are cruel and irredeemable, less than human, monsters who walk the earth in human guise. Such a story is a necessary act of self-defense and laced with the truth of their suffering. When people who remind victims of their oppressors handle the victims’ stories, however respectfully, a post-traumatic response can be triggered. Trust must be earned through a process that is never quick or easy. We need to be patient with one another and learn to discern when tentative efforts at truth-telling are emerging in our midst.

Let’s not get side-tracked by a rivalry over whose story it is because the story is shared, it belongs to all of us. Violence is a relationship built on lies. The only question worth asking is this: Can oppressors and victims learn to tell a more truthful story, a shared story? If we are to find a way to heal the trauma of oppression, it cannot be by walling our stories off from one another. We must bravely appropriate the truth wherever we find it in order to revise the story told by cultures of violence. Only then we will begin to expose the lies we have believed in for too long. Only then will we discover the truth that violence is never good and that it destroys the goodness of those who use it. That’s a new story we all can live with.

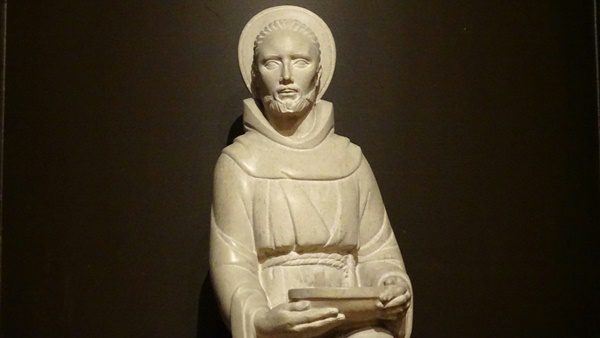

Image: Photo by PC Bro via Flickr. Available via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. Image modified.

Stay in the loop! Like Teaching Nonviolent Atonement on Facebook!