Violence is on the loose in Iraq and Syria this summer. The Islamist extremists known as ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), seeking to install a Sunni caliphate spanning the border of these two countries, have shown no qualms about using violence against their Shiite enemies. Many in the news media are labeling this as an Islamic Holy War because of observations like this one from Richard Engel, NBC Chief Foreign Correspondent: “Iraq Shiites are getting ready for battle. At the Buratha mosque today, they swear to fight Sunni extremists to the death.”

Violence is on the loose in Iraq and Syria this summer. The Islamist extremists known as ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), seeking to install a Sunni caliphate spanning the border of these two countries, have shown no qualms about using violence against their Shiite enemies. Many in the news media are labeling this as an Islamic Holy War because of observations like this one from Richard Engel, NBC Chief Foreign Correspondent: “Iraq Shiites are getting ready for battle. At the Buratha mosque today, they swear to fight Sunni extremists to the death.”

Questions about the relationship between religion and violence once again rears its ugly head. It must be stated that ISIS is a militant group and most Sunnis are horrified by their actions. But when Muslims battle Muslims in the name of God, declaring it to be a “holy responsibility,” we naturally ask theological questions about Islam. We want to know what Islam has to say about God, especially what Islam says about the use of violence in God’s name, but we should also ask what Islam has to say about Satan.

In the Footsteps of Satan

The Qur’an states that God and Satan offer two models for humanity; one is merciful and gracious, the other is vengeful and violent. We will follow in the footsteps of one model or the other. We in the West don’t want to be “followers.” We are told to be our own selves and to do that we need to be unique by not following anyone. Being a follower brings a sense of shame, but the fact is that we are constantly following cultural models, be they politicians, movie stars, professional athletes, or religious leaders. There’s no shame in being a follower. In fact, it’s part of what makes us human.

The question is not whether you will follow someone. The question is whom will you follow.

It’s a tricky question, especially when it comes to God and Satan. But the Qur’an is clear about the differences. Satan tricks humanity into following in his footsteps. The Qur’an states, “You who believe, enter wholeheartedly into submission to God and do not follow in Satan’s footsteps, for he is your sworn enemy” (2:208). In Surah 4:119, Satan tells God what he will do to humans: “I will mislead them and incite vain desires in them…I will command them to tamper with God’s creation.” The verse then warns, “Whoever chooses Satan as a patron instead of God is utterly ruined.”

Whoever chooses to follow Satan is utterly ruined because Satan’s footsteps lead to hatred, enmity, and violence. The Qur’an states that “Satan seeks to incite hatred and enmity among you” (5:91). All of the hatred and enmity that we see throughout human history has nothing to do with God; rather, it’s the result of satanic deceptive plan to pit us against one another. According to the Qur’an, if we are feeling hatred or enmity toward anyone, it’s a good indication that we have chosen to follow in the footsteps of Satan.

God-Consciousness

The Qur’an encourages us to reject the hatred, enmity, and violence that Satan incites, and instead to follow in the footsteps of God. In Surah 7.26-27 God speaks to all of humanity, “Children of Adam, We have given you garments to cover your nakedness and as adornment for you; the garment of God-consciousness is the best of all garments—this is one of God’s signs so that people may take heed. Children of Adam, do not let Satan seduce you.” It’s important to understand what “God-consciousness” means. God, as opposed to Satan, has no enmity or hatred. God’s consciousness is revealed at the beginning of 113 of 114 surahs, or chapters, of the Qur’an: “In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful.”

God’s consciousness is Grace and Mercy, and the children of Adam are meant to put on that consciousness. In his commentary on the Qur’an, Abdullah Yusuf Ali explains the implications of God’s Grace and Mercy, stating that God’s,

Mercy may imply pity, long suffering, patience, and forgiveness, all of which the sinner needs and God Most Merciful bestows in abundant measure. But there is a Mercy that goes before even the need arises, the Grace which is ever watchful, and flows from God Most Gracious to all His creatures, protecting them, preserving them, guiding them, and leading them to clearer light and higher life (14).

Putting on the garment of God’s Gracious and Merciful consciousness has practical implications for how “the children of Adam” deal with violence in our world. We must refuse to mimic the hatred and enmity directed against us and we must refuse to use violence in the name of God. Instead, in imitation of God’s consciousness, we must strive to respond to our enemies with grace and mercy. Islam’s answer to violence is summed up by the Qur’an in surah 41:34-36, “Repel evil with what is better and your enemy will become as close as an old and valued friend…If a prompting from Satan should stir you seek refuge with God.” Whenever Satan stirs us with hatred and enmity, the Qur’an advises us to seek refuge in the Grace and Mercy of God.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s Answer to Violence

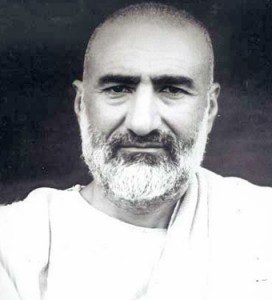

Because this explanation of God and Satan in the Qur’an may sound naïve or just plain wrong to many, it’s important to note the many Muslims who have chosen to put on the garment of God’s conscious Grace and Mercy. For example, Abdul Ghaffar Khan and his 100,000 Muslim nonviolent army repelled their enemies’ evil with something better: love and nonviolence.

Because this explanation of God and Satan in the Qur’an may sound naïve or just plain wrong to many, it’s important to note the many Muslims who have chosen to put on the garment of God’s conscious Grace and Mercy. For example, Abdul Ghaffar Khan and his 100,000 Muslim nonviolent army repelled their enemies’ evil with something better: love and nonviolence.

Khan was born into a Pathan tribe in 1890 in the Northwest Frontier Province of British India. Pathan culture was well known by the British to be fiercely violent and cruel. Pathans were stuck in a cycle of internal feuds that culminated in revenge killings. This cycle of violence turned against the British. The British Empire was locked in a series of wars with the Northwest Province. The British were successful in the First Afghan War of 1838, but in 1842 the Pathans sought revenge, massacring a British force of 4,500. Satanic hatred and enmity was rampant among the Pathans and the British people respectively, each believing their own violence was justified because of the barbaric acts of the “other.”

Ghaffar Khan knew this cycle of violence was self-destructive and had to change. There was a better way, and Khan found it in his faith. He stated that “Islam is amal, yakeen, muhabat (work, faith, and love) and without these the name ‘Muslim’ is sounding brass and tinkling cymbal.” (Nonviolent Soldier of Islam, 63). His interpretation of the Qur’an led him to live a life of mercy, grace, and nonviolence in the face of British oppression.

Under the influence of Gandhi, Khan made speeches to his people about nonviolence. Many Pathans who were deeply rooted in a culture of violence, dropped their weapons and adopted a life of nonviolent resistance against British occupation. Khan formed a nonviolent army called Khudai Khidmatgars, or “Servants of God.” How did they serve God? They refused to use violence in the name of God and they refused to mimic the violence of their enemies. Instead, they would follow in the footsteps of God by offering forgiveness. The Servants of God signed a contract in which they stated:

I am a Khudai Khidmatgar; and as God needs no service, but serving his creation is serving him, I promise to serve humanity in the name of God.

I promise to refrain from violence and from taking revenge. I promise to forgive those who oppress me or treat me with cruelty.

I promise to refrain from taking part in feuds and quarrels and from creating enmity.

I promise to treat every Pathan as my brother and friend.

I promise to refrain from antisocial customs and practices.

I promise to live a simple life, to practice virtue and refrain from evil.

I promise to practice good manners and good behavior and not to lead a life of idleness. I promise to devote at least two hours a day to social work.

Khan put on the garment of God’s conscious Grace and Mercy. His understanding of God as loving, merciful, and compassionate was at the heart of the movement, therefore they would forgive everyone, including their enemies. The surprising thing was that this radical belief in love, nonviolence, and forgiveness worked! Pathan violence didn’t work. It only sowed satanic hatred and enmity among the British people. Pathan nonviolent resistance allowed the British to see their own violence and the suffering it caused for what it really was: satanic, absurd, and inhumane.

Khan played an integral role in ending the British occupation of India, but unfortunately, few today have heard of him. His dedication to modeling his life after God’s Mercy and Grace led him to forgive and love his enemies even in the face of brutal violence is a great example for Muslims and non-Muslims alike. He is a beacon of hope for our strange world that continues to travel toward destruction and violence. Khan shows us that the way to change hearts and minds is not through violent actions or violent words, but through faith, love, and nonviolence.