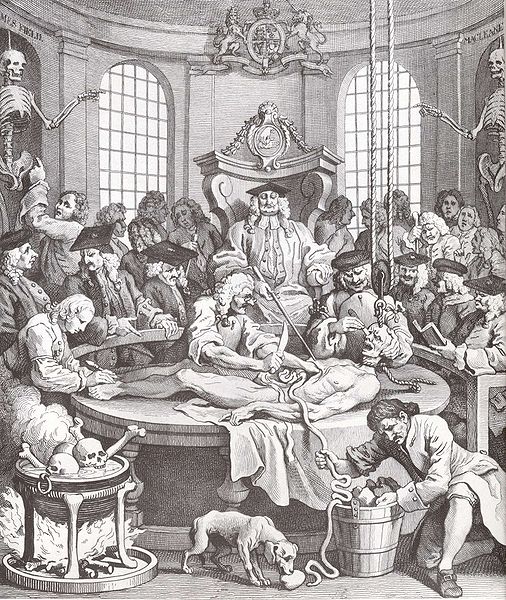

In The Four Stages of Cruelty, William Hogarth depicts the body of Tom Nero, a fictitious murderer, being dissected during an anatomy class. From the ceiling hang the skeletons of Burke and Hare, the infamous grave-robbers. Tom Nero might never have existed, but the fate of his mortal remains was entirely plausible: in 1752, the British Parliament had passed a law, permitting the authorities to donate the bodies of executed criminals, as it were, to science.

Hogarth was preaching a homily in images. His moral: break the sixth commandment, and you will pay a terrible price. Not even your body will be yours to do with as you please.

Most people today would find the image shocking, and the reality behind it downright barbaric. Since Georgian times, the idea that human mortal remains deserve some minimum level of decent treatment has become part of the Western social compact. The bodies of the indigent are buried in Potters’ Fields, in deep, regular graves. Painstakingly, DNA experts tested the fragmentary remains of 9/11 casualties, in order to return them to their loved ones. Even Osama bin Laden — who, God knows, did nothing to endear himself to his body’s final custodians — was disposed of with as much reverence and probity as he could have expected, given the circumstances.

On the subject of bin Laden, public figures with views as diverse as Sarah Palin and Jon Stewart are demanding that photographs of his body be released for public consideration. This is no more a part of Western SOP for handling the dead than grinding them into sausages. Yet bin Laden’s vicious history makes it seem reasonable. Even if you disagree with Palin, that providing evidence is “part of the mission,” even if you reject the arguments that sight of bin Laden’s bullet-shattered face will inflame the Islamic world or amount to a football-spiking, there doesn’t seem to be much reason not to do it. As Stewart points out, graphic images of death are all over the internet, not to mention al-Jazeera. Why pick this moment, of all moments, to turn squeamish?

My answer would be that releasing the photos would involve a special directedness. There’s not much chance the pictures will make it onto the net without government say-so; we can’t speak of them as already belonging to some amorphous “dialogue.“ The figure in the photos is more than part of the landscape in a wide-angle battle scene; it is the scene. The person to whom it belongs is not anonymous, and cannot be seen as generic. No, it belongs to someone whose name and history are widely known; indeed, his notoriety is the very justification for showing them. In this case, the violation of the norm stating that dead bodies deserve some privacy, especially when they look their worst, would be knowing and deliberate.

In Touchstone, Wilfred McClay writes: “…there is something of primal importance about the way we treat the dead…Nothing tells us more about a culture’s regard for the human person and its sense of itself than its funerary rituals, its ways of acknowledging and remembering the dead.” If we invite the public to gawk at bin Laden’s corpse we will begin to qualify that statement. We will send the message: We believe in treating the dead with reverence most of the time. Kinda-sorta. Unless, as the legalese goes, we have a compelling interest not to.

Observers have cited no end of compelling interests. The problem is, I don’t find most of them very compelling. The one that, to my mind, holds the most water, comes from Jon Stewart, of all people. In Wednesday’s monologue, he observed, “We can only make decisions about war if we know what war actually is.” That’s a noble purpose: not to spike the football, not to placate the implacable conspiracy buffs, not to warn our enemies — who, as Stewart pointed out, can find all the caveats they’ll ever need on al-Jazeera — but to give people a peek behind warfare’s seductive jargon.

But there remains the question of what, exactly, people will see. In an essay titled “Looking at War,” Susan Sontag makes a case that images of war are never just images of war. Instead, they’re images of particular wars, fought by particular groups of people, who are trying to advance particular agendas. Where people stand on those agendas is going to influence, if not determine outright, what meaning they attach to the images.

“To an Israeli Jew,” writes Sontag, “a photograph of a child torn apart in the attack on the Sbarro’s pizzeria in downtown Jerusalem is first of all a photograph of a Jewish child killed by a Palestinian suicide bomber. To a Palestinian, a photograph of a child torn apart by a tank round in Gaza is first of all a photograph of a Palestinian child killed by Israeli ordinance.”

To put that another way, most people already have mental boxes into which they can fit any photo of bin Laden, no matter how grisly it might be. To many people, it will represent a football well and justly spiked. To others, it will only serve to confirm that the U.S. is imperialistic and brutal. One thing that photo won’t do — at least in most cases — is teach anything new.

The danse macabre motif that flourished after the Black Death first hit Europe showed death visting all ranks — kings and peasants, men and women, presumably good as well as evil. Death is the great equalizer, the message went. That’s not entirely true — even death has its own caste system. Anyone who doubts it should compare the tomb of, say, St. Bernadette with any of the banal, flat brass-fronted grave markers that are so common in modern cemeteries. But if we make bin Laden’s body the property of the world, we’re suggesting that death has its outcastes and untouchables. I’m not sure I’m ready for that.

— Max Lindenman

As an afterthought, I’d like to clarify something. When I post an opinion on some issue of substance — as opposed to, say, recommending a movie — the opinion is mine and mine alone. Nobody should ascribe it to Elizabeth, much less to some impersonal, authoritative Anchoress editorial staff. If you find any of my opinions wrongheaded or offensive, lodge all the blame with me.