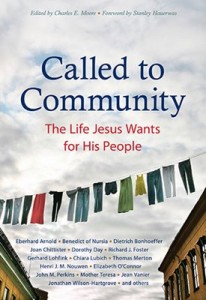

I write today for the purpose of recommending “Called to Community: The Life Jesus Wants for His People,” the latest book from Plough Publishing. Edited and introduced by Charles Moore, with a foreword by Stanley Hauerwas, “Called to Community” is an essential collection of 82 essays and perspectives on the broad themes of a call to community, forming community, life in community, and engaging the world through community.

Plough Publishing is an arm of the Bruderhof (“place of brothers”), an Anabaptist religious community founded in 1920 in Germany by Eberhard Arnold, a young dissenting Protestant theologian. Members live in community, eschew private property, work and worship together, and like other sects in the Anabaptist tradition are rigorously pacifist. Their theology is conventionally Evangelical, but one of their hallmarks is a joyful, capacious ecumenism.

Plough Publishing offers high-quality books and an eponymous quarterly magazine. I’ve been a Plough subscriber since the magazine returned to print in 2014 after a twelve-year hiatus as an online-only product. Each issue is a treasure trove of thoughtful articles and essays on a given theme by a wide range of authors.

The Winter 2016 issue, for instance, was on the theme of “Mercy” and featured an essay by Gerhard Cardinal Muller, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, an interview with Evangelical writer and longtime Christianity Today columnist Phillip Yancey, a story by Leo Tolstoy, a short piece titled “Forgiving Dr. Mengele” by a Holocaust survivor named Eva Mozes Kor, and other really great, inspiring content.

Then there are the books. I first became aware of Plough Publishing shortly after their 1988 release of a book titled “The Gospel in Dostoevsky,” a compact collection of excerpts from “The Brothers Karamazov,” “The Idiot,” “Crime and Punishment,” and other works, with introductions by the Reformed theologian J.I Packer and the Catholic convert Malcolm Muggeridge, who first brought Mother Teresa to world attention with his book, “Something Beautiful for God.” Subsequent books from Plough have been of equal qualify and similarly edifying. “Called to Community” is no different.

The selection of authors is inspired. They range from familiar names like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Henri Nouwen, Thomas Merton, and the Bruderhof founder Eberhard Arnold to relatively obscure contemporary writers like Jodi Garbison of the Cherith Brook Catholic Worker in Kansas City and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, a young leader in the New Monasticism movement. Dorothy Day, St. Benedict, Chiara Lubitch, and Soren Kierkegaard make appearances, but so do Mennonite writer David Janzen and Andy Crouch, executive editor of Christianity Today.

While each of the essays in this volume will challenge and inspire you, a few stood out for me. Alden Bass traces the history of Christian reform movements from the Book Acts to the 20th Century. Along the way he convincingly demonstrates that with the notable exception of the Reformation itself, the formation of intentional communities was critical to each. “The communities mentioned here,” he writes, “are but a sampling of the thousands of groups of Christians who have determined to live lives of intentional discipleship in communities modeled on the Jerusalem church … … seeking to experience the presence and power of God in the shared life of community, a preparation for the great communion to come.”

In his essay “It Takes Work,” Charles Moore, the editor of this collection and a member of the Bruderhof, frankly confronts the challenges that face those who would live in community. “Community is a nice ideal,” he writes, “but are we ready to do the work it takes to forge a common, committed life with others on a daily basis, especially if it costs us?” He goes on to itemize the goods one must be prepared to share with “one another” in order to make it work – time, space, authority over the self, private possessions, our sins and burdens – and the difficulties these entail. He brilliantly synthesizes St. Paul’s teaching on what we owe to one another, and notes that the early Christians “did not just occasionally fellowship (verb); they were a fellowship (noun). They didn’t go to church; they were the church.

The section on Life in Community includes a number of essays that focus on particular challenges of lives lived together. They include Joan Chittister on embracing difference, David Janzen on resolving conflicts, Elizabeth O’Connor on establishing dialogue, Jean Vanier on the ever-thorny problem of leadership, Jodi Garbison and Jenny Duckworth on money, Moore again on children, and so forth. Near the end of the section is a brilliant series of short pieces on the topic of repentance that highlight the need for both confession and discipline in the context of community. It’s tough stuff, but essential for anyone seriously contemplating building a common Christian life with others.

My favorite section was the last, Beyond the Community. In his essay, “Revolution,” John Perkins, founder of the Christian Community Development Association, notes that, “the movement of Christian community … could very easily end up in groups of white, middle-class Christians talking themselves out of the loneliness and meaninglessness of the suburbs. It could end up as a new form of withdrawal from the realities of evil in our systems into a new form of communal materialism.”

Perkins is dead on here. Although much of contemporary American life is characterized by what Charles Moore calls the diseases of “superficiality and rootlessness” with “shallow friendships and fragile relationships,” there is always the risk that the bourgeois spirit could transform even Christian common life into another form of anesthetizing and self-congratulatory isolation. As a prophylactic against this sort of distortion, Perkins offers “relocation, reconciliation, and redistribution,” which together signal the revolution he has in mind

“First,” he says, “we must relocate the body of Christ among the poor and in the area of need.” By relocation, he doesn’t mean hanging out a shingle and offering services, which many Christian organizations do now. He means that, “some of us people voluntarily and decisively relocating ourselves and families for worship and for living within the poor community itself.

Second, “we must reconcile ourselves across racial and cultural barriers.” This is vital not only for the experience of diversity, but as a witness to reconciliation, “a showdown between the power of God and the depth of the damage in us as human beings.” Christ reconciles us to the Father, and we become the Body of Christ when we are reconciled to one another.

Finally: redistribution, that dirty word in American culture. “If the blood of injustice is economics,” writes Perkins, “we must as Christians seek justice by coming up with means of redistributing goods and wealth to those in need.” He doesn’t mean aping the federal government’s fund-and-forget strategy. He means creating genuine economic support systems that “develop a sense of self-determination and responsibility with the neighborhood itself.” Through these systems, “the body of Christ becomes the corporate model through which we can live out creative alternatives that can break the cycles of wealth and poverty that oppress people.”

The remainder of the essays in the final section are equally good, especially the piece that closes the book. It’s by our particular inspiration, Dorothy Day, and titled “Mercy.” The original essay appeared in Commonweal. In it she tells a story that illustrates the risks of community.

Here is a letter we received today: “I took a gentleman seemingly in need of spiritual and temporal guidance into my home on a Sunday afternoon. I let him have a nap on my bed, went through the want ads with him, made coffee and sandwiches for him, and when he left, I found my wallet had gone also.”

I can only say that the saints would only bow their heads, and not try to understand or judge … These things happened for our testing. We are sowing the seed of love, and we are not living in the harvest time. We must love to the point of folly, and we are indeed fools, as our Lord himself was who dies for such a one as this.

For those who are discerning the call to community, this book is a sign of confirmation from the Holy Spirit. At least it has been for me. I not only recommend “The Call to Community.” I thank my brothers and sisters in the Bruderhof for publishing it. They have done the church a great service.