Those of you who know me know I have a few hobby horses I come back to rock on whenever I get the chance. Montessori education. Gardening. Homesteading depopulated upper mid-western cities. Food. Urbanism.

Those of you who know me know I have a few hobby horses I come back to rock on whenever I get the chance. Montessori education. Gardening. Homesteading depopulated upper mid-western cities. Food. Urbanism.

I’m back onto homesteading cities today. I’ve advocated in the past for something like an Urban Homesteading Act. While I still think that or something like it needs to happen, the problem with folks just moving wholesale to American rust belt cities is that there are no or sharply limited jobs – that’s what has turned them into a ‘rust belt’. And it’s tough to be an entrepreneur anywhere, but especially in a cash strapped region. So ultimately I’ve found it hard to press on this subject- I haven’t really seen a practical way to make it all come together for folks. This may no longer be true.

I’m reading a book called The Urban Farmer: Growing Food for Profit on Leased and Borrowed Land, by Curtis Stone. In it, Mr. Stone details how he’s grossing $75,000 USD a year on less than ½ an acre of land using minimal season extension, in British Columbia. In a nutshell, he’s using an agricultural approach called SPIN (Small Plot INtensive) farming, and selling a small cadre of only the most profitable crops, to three demographics: his local farm market, local restaurants, and CSA customers.

He’s earning $75,000 a year on city lawns. With his bike.

So this brought me back to thinking people really can be entrepreneurs in the rust belt, especially when I took a look at what folks are doing on the SPIN website, and how folks are turning a profit in 6 months time. Now no one is earning a fortune, and folks are working some long hard hours in the thick of the growing season- but this isn’t the typical story of agriculture being a dead-end job where no one earns a living. All the barriers to entry are fairly low. It also makes me wonder about the potential of micro dairies and aquaculture in this framework of intensive, small scale farming. Seriously, what about a small herd of dairy ruminants that spent their days eating all the overgrown grass on vacant city lots, providing a cash flow not just for ‘mowing lawns’, but also for the milk they produce? Why couldn’t pools (or tubs in garages) be converted for growing shrimp and fish for the same markets that are buying vegetables? Again, none of these models are making anyone a six figure salary but folks are making and can make a living growing and selling something everyone needs: food. Even if you have little to no money, you need food and you pay something to get it.

Urban agriculture as an answer, however, only raises all kinds of questions. If you’re going to have urban dairy, what about all the manure? Can this entrepreneurial model work everywhere? Zoning? Neighbors? What about food safety? Is it even legal? This is where I think developers come into this idea. If there are folks working on incremental development, they can catalog available land and resources in a city, check it against the local regulations and develop properties that are tailor-made to the needs of SPIN farmers. They can even build some of the local relationships that will be needed to facilitate success for these micro agricultural enterprises. The incentives are aligned for the developer to smooth a clear path for the sort of buyer she is hoping to attract, and to increase the chances of success for the buyer to be successful enough to pay for the property.

The last thing that I think is missing–but can grow–is a culture of food security and in(ter)dependence. We have an indigenous history to build on, but where I think we’re aiming is at a food culture similar to Russia’s dacha gardening.

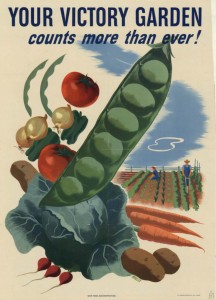

Russia’s gardening success is quite remarkable: using but a very small portion of the arable land, citizens grow roughly half of their food, in some of the shortest growing seasons on the planet. It bears noting that more than food grows in those gardens. Right alongside the crops grows community knowledge of growing, processing, and storing that food, and a cultural attitude that your food comes from the community you live in. And we can do it here–we have grown food on approaching that scale in Victory Gardens. In four short years, American Victory Gardens were producing 40% of the vegetables in the US. When the push for gardening ended along with the war, and gardens weren’t planted, there was nearly immediately a food shortage. These small gardens–sometimes just containers on window sills–were the difference in food security for Americans.

Not only do we have this cultural memory, but we have vibrant agricultural extension offices throughout the country, literally waiting to help with the effort of communities to grow food for themselves. I mention this aspect of a ‘culture of food security’ because, right now, most Americans see food insecurity as normal. Most folks understand food as coming from a store, and may well rebuff or openly reject the very real value of a patchwork of tiny local farmsteads producing food in their communities. And that–even more than the cost of entry, and the juggling of regulations, and the work of raising food–blocks the viability of micro farms as part of the resurgence of rust belt cities.

I think this is still only a partial answer to repopulating the upper Midwest. We can’t every one of us be a farmer, although many, many of us without question should and there’s no reason a community can’t support a variety of agricultural enterprises. But places and people need more than raw ingredients to eat. We need places of beauty to live in, and clothes to wear, and books to read, and the list is goes on. Then also, asking folks to shift their mores about where their food comes from is not actually a small task. Yet, taken together, these ideas bring the barriers so low, it seems like a natural first step in the right direction.