A question for these troubled times in the Church and perhaps in our personal faith commitment:

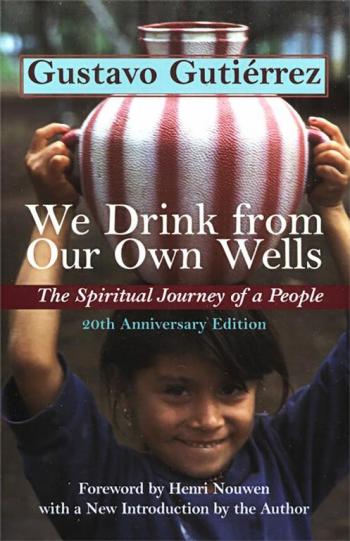

What if spirituality were a community enterprise? This is the question theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez asks in his beautiful meditation, We Drink from Our Own Wells, originally published in 1984 with an introduction by Henri Nouwen and reprinted with a new preface by the author in 2003. (The book’s title is a sentence from Bernard of Clairvaux, “we drink from our own wells,” i.e., from our own experience and sources.)

Spirituality in a communal sense is an odd-sounding idea, especially to us Americans who have succeeded so well in privatizing spirituality, as we have with so many other things. To explain our condition, Gutiérrez argues for a split after St. Thomas between spirituality (the the root) and theology (the fruit). And yet spiritualities are ultimately the source of theological systems, as the author points out, citing theologian Marie-Dominique Chenu. That includes the “system” of liberation theology, which is grounded in a Latin American spirituality taking shape among the poor.

Gutiérrez has another timely question for us: why are North Americans not spiritually free but instead imprisoned by various forms of fear and guilt? Is it because we have managed to spiritualize spirituality, even turning the fierce stanzas of the Magnificat into “Mary’s sweet song”?

Nouwen recounts his experience in 1982 of hearing Gutiérrez’s first lectures in Lima on his spirituality of liberation, a Christ-centered (not, please note, Marx- or politics-centered) method which is much greater than any politics. It is also, as Nouwen learned, about the social dimensions of humility, faithfulness, obedience, and purity. What does this mean?

In Latin America, to speak of the social usually means to speak of poverty. And as Gutiérrez has written, poverty means death: physical, psychological, cultural. He asks us, does God want poverty? Or does He want our spirituality to be liberatory, setting us free to love?

What is going on in Latin America today, suggests the author (writing in 1984 but accurate for 2020) is an experience which is giving birth to a distinctive way of being Christian. The accompaniment of the poor means we are making “a way established in the walking, in the going,” as the poet Machado (quoted by the author) put it. Pope Francis, who may have enabled Gutiérrez’s shift away from a more Marxist approach to liberation theology in favor of his teología del pueblo, is very much a part of this movement in the global South.

Moreover, as Nouwen came to believe, the spiritual destinies of North and South America are linked.

Which leaves us with a final question: are we in the Church of the North ready to put aside violent nationalisms and imagine, as St. Pope John Paul II urged, one Catholic — and Marian — continent?