on this difficult anniversary,

i wanted to share something i wrote

about that september morning a decade ago…

below is a chapter from my second book, sin boldly,

a memoir (and field guide) about grace.

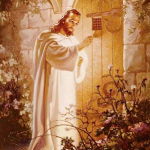

may you feel the closeness of the Spirit

and the staggering grace of God

in a powerful way today and always.

blessings and big love,

cathleen

DRIVING AND CRYING from SIN BOLDLY: A FIELD GUIDE FOR GRACE

After being in the newsroom around the clock for a couple of days after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, I came home exhausted and broken — spiritually, emotionally, mentally. I collapsed on the futon and turned on the TV just as U2 began to play live from London during the international 9/11 telethon.

And if the darkness is to keep us apart

And if the daylight feels like it’s a long way off

And if your glass heart should crack

And for a second you turn back

Oh no, be strong

Walk on, walk on

It was precisely what I needed to hear. Not from a rock band, not from any other human being. It’s what I needed to hear the Creator of the Universe say.

That moment of grace in the guise of a song reminds me of something I once heard the author Frederick Buechner say: “Pay attention to the things that bring a tear to your eye or a lump in your throat because they are signs that the holy is drawing near.”

One perfect summer night a few years ago, the holy, as it does, snuck up on me in the most random of places. A peachy gloaming lit the western skyline as I drove home, top down on my ancient Miata, through the quiet rough-and-tumble streets of Chicago’s west side. Blaring from the tinny speakers I’d cranked up to almost 11 was one of those songs that makes me sing at the top of my voice (even in a convertible) and throw my hands in the air — “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” by the Rolling Stones.

Driving while listening to music is one of life’s great pleasures. It’s a spiritual practice I learned from my father. When I was a little girl and he was working on his doctorate at Columbia University in New York City, sometimes I would accompany Daddy on the ride from our home in Connecticut into Manhattan. Many of my fondest memories from early childhood are of those regular road trips in his Karmann Ghia, whizzing along the Henry Hudson Parkway, listening to his favorite traditional jazz station on the AM-only radio, talking about nothing in particular, and eating Cracker Jacks from the box he always kept in a hidden compartment behind the cushions of the backseat.

Years later, when I got my driver’s license, I would spend hours driving back roads, singing along to cassette tapes of my favorite bands or the alternative radio station out of Long Island that I could tune into in the car but not in my bedroom at home. I do my best thinking in the car, taking the scenic route and the long way home to stretch even a quick run to the supermarket into a contemplative journey, alone with my thoughts and some righteous tunes. There’s something about the insulated solitude of a car that gives me permission to sing with abandon while working on various existential conundrums.

As I rolled up to a stoplight near the United Center (home of the Chicago Bulls and Blackhawks) that summer night, the Stones song ended and a familiar voice took to the airways, hitting me upside the head with some unexpected spiritual wisdom, leaving me gobsmacked (or, more accurately, God-smacked). It was Lin Brehmer, the radio station’s most popular disc jockey, reading one of his “Lin’s Bin” essays, this one an answer to some listener mail — a letter from a fellow in Indiana who asked, “I’m not getting any younger. Should I start going to church? If so, which one?”

The DJ’s answer, in part, was this:

As we get older, we begin to consider our mortality. The godless man might ask himself at the end of his life, “Have I miscalculated? Should I have communed with my maker?” Even W.C. Fields, a man known more for his hatred of kids than his love of religion, was discovered late in life with a Bible on his hospital bed. “Bill,” a friend, asked, “what are you doing reading the Bible?” and Fields replied, “Looking for loopholes.” . . . Finding your faith later in life brings a different perspective to religion. Still, watching a child you know grow up and solemnify their belief in front of family and friends will move you in mysterious ways. Is this the same baby in a stroller now chanting in Hebrew? A sweet three-year-old girl I know was once at Mass, and as the bewildering experience wore on, she became impatient and beganto squirm. Her mother tried to placate her by pointing out a picture of the Christ child. In a voice that reverberated to every chamber of the stone cathedral, the innocent shouted, “I HATE THE BABY JESUS!”

Now, here comes the part that got to me, taking me by surprise and bringing tears to my eyes.

“Before you wonder at the consequences,” Lin said, “remember what Jesus himself said: ‘Suffer the little children, and forbid them not to come unto me,’ because I can take it.”

Whoa. That’s about as profound a religious statement as I’ve ever heard. And it’s not exactly what you might expect to hear between rock anthems on Chicago’s premiere rock ’n’ roll radio station. But WXRT is not your average radio station and Lin Brehmer is not your average disc jockey.

He is known, in fact, as “The Reverend of Rock ’n’ Roll.” It’s a moniker Lin earned in the early 1970s when he was a young DJ in Albany, New York, where he hosted a show on Sunday mornings. It’s a nickname fellow jocks bestowed on him because of his proclivity for reading from “Book Nine” of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, particularly the line that says, “Shall that be shut to Man, which to the Beast is open?”

“OK, mister, I think it’s time you and I had a chat about this ‘Godstuff,’ ” I told “the Rev.” in an email after I heard him read the essay titled “Choosing Faith,” the one that had moved me so deeply. Never one to flee from a dare, Lin gamely acquiesced to a thorough grilling in his office at the radio station, and, as is often the case when I go looking for God in the places some people would say God isn’t supposed to be, what I discovered was much more intriguing than I could have imagined.

I have a favorite T-shirt that reads, “Jesus is my mixtape.” When I bought it, I thought its slogan was charmingly quirky, but over time it has acquired this transcendent quality, a motto that sums up my belief that everything — everything — is spiritual. At the center of that everythingness, as a pastor friend of mine likes to describe it, is a universal rhythm, a song we all play, like a giant, motley orchestra. Sometimes in tune, sometimes off-key. We call it by different names. Still, it remains — if only we have ears to hear it — the eternal soundtrack that plays in the background of our lives.

For the nearly twenty years that I’ve called Chicago home, WXRT has provided the (literal) soundtrack to my life. It was the first radio station I tuned to when I arrived in Illinois in the fall of 1988 to start my freshman year at Wheaton College, and it’s still the station I’m tuned to while driving or cooking in the kitchen or just puttering around the house. Since 1991, except for the days when I oversleep, Lin has been the morning mixtape master, spinning the music that starts my day. In 2002, Lin began reading on the air his thrice-weekly “Lin’s Bin” essays, running the gamut from the silly (“The Hokey Pokey: Is That What It’s All About?” for instance) to the blatantly spiritual.

The morning I turned up at the radio station to grill Lin about God, he had just finished his morning broadcast and was reaching for an ancient, bedraggled copy of Norton’s Anthology of English Literature (in two pieces with no cover) as I walked through the door of his office. “I’ve always been fascinated by religion and man’s relation to the divine,” Lin told me flipping pages in the book to find Paradise Lost so he could read from his favorite passage. “I’m a mystical expressionist,” he says. “I take the idea of mysticism very seriously, but I sort of paint it my own way. I think the idea that there is something within each and every one of us that can take us to a place we’ve never been before is what makes it great to be alive.”

Music is a vehicle that propels Lin — and me and so many other people — toward a place we might call Grace. Music is part of our cultural conversation, and in nervous times like these, it has a lot to say. The idea that music has the power to move people in a way nothing else does seems never to be far from Lin’s mind. “People ask me why I got into radio,” he says, “and for me, it was almost always a musical thing, almost as if I wanted to preach by playing songs that said something.”

The musicians that shaped his consciousness as a teenager — Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, the Beatles — were more than just drug-addled rock stars. They were prophets, Lin says, warning us about the future, just like Jeremiah and Ezekiel did in the Hebrew Scriptures.

Modern musical prophecy didn’t end when the Summer of Love drew to a close in 1968. Lin keeps on his desk at the radio station a framed picture of his teenage son, Wilson, playing a blue Fender Stratocaster guitar. It reminds him that music has the same effect on Wilson and his peers that it did on his father as a teenager.

“I absolutely think that teenagers or young people are as much affected emotionally and spiritually by the music they hear as by any sermon they hear in a church,” he told me without a hint of bitterness or sarcasm in his voice. “Part of the reason I have trouble going to church and staying in church is feeling like the sermon some minister is espousing wasn’t connecting with me in any way, whereas a good four lines from a John Hiatt song could mean so much more to me.”

As someone who had her first spiritual epiphany at the age of twelve while listening to U2’s “Gloria” for the first time after school in a friend’s living room, I can attest to this. The message can even be the same — sometimes, as was the case with “Gloria,” the words themselves are the same — as what we hear in church or temple, mosque or shul. But there’s something mightily powerful about hearing the words sung aloud with passion or pathos, as a guitar wails and a bass line thumps.

What brings a tear to the eye of one person is not the same thing that puts a lump in the throat of another, but for everyone there is some music that changes their life. Whether it’s some pop cutie-pie on American Idol warbling a song written by committee or Tom Waits grunting through “Swordfishtrombones,” there is some music that gets inside of everyone. For Lin, it’s music like “Good Day for the Blues” by Storyville, “Gimme Shelter” by the Rolling Stones, or Bob Dylan’s “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).”

For me, it might be Jeff Buckley’s “Hallelujah,” “Not While I’m Around” from the Stephen Sondheim musical Sweeney Todd, or “Nessun Dorma” from Puccini’s opera Turandot. (The rousing, climactic verse, “Tramontate, stelle! All’alba vincerò! Vincerò! Vincerò!” reduces me to a puddle every time I hear it.)

“You talk about what your religious faith is supposed to do for you and what a minister or a rabbi is supposed to do for you, providing you with counsel and wisdom and sustenance and support — sometimes the quickest avenue to all of those things is a song that you love,” Lin says. This reminds him of music he also associates with 9/11. “The day after September 11, I opened my show with a song I never play just as a song. Now it’s the first song I play on the anniversary of 9/11 every year. It’s called ‘Sunflower River Blues’ by John Fahey. It’s a very simple acoustic guitar instrumental. But for me,” he says, leaning forward in his chair, his voice dropping, “it has that same feel as the second movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony.”

“Dunnnn dun dun dun, dunnn dunn, dunn dun dah dunn — it kind of plods along, but there’s a kind of resolution in the musical phrasing, and it’s the same thing in that John Fahey song. It’s got a certain melancholy feel to it, but at the end it kind of resolves itself in a major chord that makes you think everything’s gonna be OK,” he said, smiling wistfully. “It’s gonna be all right.”

That day at the radio station, as Lin expounded on music’s more mystical qualities, I became aware of a song playing quietly on the radio receiver on his desk tuned to WXRT. It was U2’s “Walk On.” When I mentioned it to Lin, he turned up the volume, and we were both struck still, as if an unexpected third party had just joined us.

[wpvideo G93TAOpn]