Death as the ultimate equalizer is one of the compelling themes at the ossuaries of Catholic Europe. Most of the thousands of human skeletons and bones on display, whether in artistic arrangements or scattered haphazardly on the ground, bear no obvious traces of individuality. The distinctions and divisions of sex, age, type of employment, and social class, to some extent, of life in highly stratified European societies are obliterated by the leveling scythe of the Grim Reaper and Reapress, in Italy and Spain.

Anonymous skulls, femurs, and rib cages, among scores of other bones, serve as memento mori in no uncertain terms. No matter our station in life, we all end up as skeletons, stripped of the flesh and blood that are are an integral part of our individuality. Until a new tradition of adorning and memorializing the skulls of the deceased emerged in the Catholic Alpine region of Austria, Switzerland, and Germany, only nobility and clergy were laid to rest at charnel houses, bone chapels, and monasteries with any markers of personhood, most importantly with name tags and vestments.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century the converging streams of Protestantism, the Enlightenment, and nascent capitalism led to a growing sense of individualism among the Western European majorities, especially the emergent bourgeoisie. Like European nobility, members of the newly formed middle classes sought to express their individuality in both life and death, and in Catholic

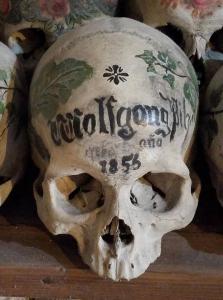

Alpine Germania one of the unique ways this maninfested was through the ornamentation and memorialization of skulls of deceased family members. And it was in the picturesque mountain village of Hallstatt where the artistic memorialization of skulls was realized most creatively and abundantly.

Western Europe’s high population density not only applies to the living. Many cemeteries across the continent became so overcrowded that after several years of decomposing six feet under, skeletons would be exhumed from their graves and placed in charnel houses, a term which derives from the Latin word for flesh, carnalis. In the 1700s St. Michael’s Church in Hallstattt began exhuming skeletons in the graveyard to make room for new arrivals.

After the skeletons were bleached in the sun and transformed from a moldy yellow to a parched white, family members would stack the bones in the charnel house next to their bony kin. The new practice of memoralizing skulls with names and dates of birth and death, as well as adorning them with painted symbols took root in the 1720s. About half of the some 1,200 skulls at the Hallstatt Beinhaus are graced by symbolic flora, such as red roses for love, laurels for victory, oak for glory, among others. The majority of the 610 crania that bear dates are inscribed with years belonging to the 1800s. By the mid-20th century, the unique Catholic tradition from Alpine Germania had faded away with the last skull admitted in 1995.

As part of the new Western fascination with death culture, especially in the U.S. and UK, the Hallstatt Beinhaus has become a trendy tourist attraction. In fact, it wasn’t easy to photograph the skulls among scores of international tourists elbowing each other in the small space. Despite the crowds, the Austrian ossuary is a poignant reminder that the now hegemonic individualism of the West, which extends beyond the grave, is of quite recent vintage, originating in singular form with the memorial skulls of Hallstatt.