Macabre isn’t usually one of the adjectives used to describe contemporary dance in its myriad expressions. Sensual, erotic, frenetic, and romantic figure among some of the images that come to mind with genres of dance such as salsa, hip hop, techno, among others. But in medieval Europe where death was omnipresent, especially during the Black Plague, even one of the forms of cultural expression most associated with joy and celebration couldn’t escape intrusion by the Grim Reaper. Originating in France in the early fifteenth century, danse macabre is an artistic genre of memento mori, mostly in the form of frescoes, woodcuts, and prints, which evokes the equalizing universality of death.

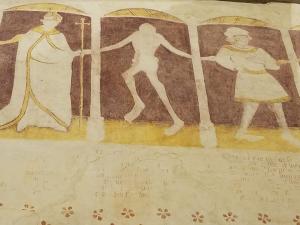

While there is some variety to genre, which was painted in churches, cemeteries, and ossuaries predominantly in France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and England between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, the dance of death involves human skeletons and men and women of all classes of medieval Europe joined in rhythmic movement. Line and circle dances were the most popular styles during the late Medieval period so most of the frescoes depict circles or lines of alternating skeletons and human beings holding hands in what is the last dance for the mortals.

Visiting the Catholic Kermaria Chapel in the Breton town of Plouha for my current research on memento mori, I was fortunate to see the last surviving ecclesial danse macabre fresco in France, which was painted on the sanctuary walls in the 1490s. What’s most striking about the faded frescoes is that all the living souls participating in the line dance of death are noblemen and high-ranking clergy. Kings, bishops, princes, and cardinals are led away to the afterlife by Ankou, the Breton, Cornish, and Welsh, equivalent of the English Grim Reaper.

Here it would seem that indeed death does discriminate – against the elite – which on one level is a radical statement for the time and place. Medieval Catholic churches tended to be places that reinforced rigid social hierarchies. On the flip side however, humble parishioners viewing the frescoes could find a measure of solace for their earthly afflictions in that Ankou, scythe in hand, was also coming to harvest the souls of the high and mighty of Brittainy and France. Here the memento mori wasn’t so much about remembering one’s own mortality but rather the inevitable demise of us all, especially those who have most enjoyed the vanities of life.