Co-authored by Dr. Kate Kingsbury* and Professor Andrew Chesnut

A widely circulated photo of Ovidio Guzman, one of the sons of notorious narco kingpin El Chapo Guzman, wearing a pendant of the Holy Infant of Atocha reminded us that it’s not only Latin American folk saints who serve as narco-saints but also a number of Catholic ones. Last week the 28 year-old narco, who has taken on a leading role in the Sinaloa Cartel in his father’s stead, was briefly detained by Mexican security forces in Culiacan. Guzman’s arrest led to an immediate mobilization of cartel sicarios who took to the streets of the Culiacan to battle security forces in a brazen display of urban warfare. The overwhelming firepower of cartel gunmen and a simultaneous prison break led Mexican authorities to release Guzman within hours, a move that was widely criticized. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, claimed he manumitted El Chapo’s son to avoid further bloodshed. Ovidio Guzman might well claim his pleas to the Holy Child had been heard.

Given that both Guzman junior and senior look to saints for protection, we thought we’d profile the major ones, both Catholic and folk varieties, that are petitioned by Mexican narcos for protection from enemies and to bring harm to their nemeses. One of the most seemingly incongruous saints supplicated by narcos is the Holy Child of Atocha, Ovidio’s apparent saviour. This infant saint originated in Spain under Moorish dominion. All the men in the city of Atocha were held captive by the Moors who permitted only young children to bring them water and food. Out of nowhere a mysterious little boy appeared with bountiful provisions for the captives. Local Catholics quickly discovered that the shoes on a statue of the Christ child at the local church were soiled and worn, which led them to believe that the mysterious boy was Christ Himself doing good deeds during the night when parishioners wouldn’t notice his absence from his station at the church.

Holy Child of Atocha

In the New World, the Holy Child appeared in the Mexican state of Zacatecas in 1554, where he performed a miracle to aid trapped silver miners and over time became the patron saint of miners in state. As the patron of both prisoners and travelers, the Holy Child of Atocha is a natural for narcos, many of whom spend time in Mexican and American prisons and of course as traffickers in psychotropics they must travel frequently, as must their shipments.

The Holy Child’s shrine at Chimayó is unambiguously associated with narco-culture as nearby Espanola is notorious as the “Heroin Capital of the Southwest” and having visited several times we can attest to the numerous ex-votos on the wall related to drug overdoses and incarcerations. However, the founding of the the shrine was unrelated to narco-trafficking. More than a few New Mexicans served in the Philippines during WWII because of their Spanish language skills, and hundreds were captured and made prisoners of war by the Japanese. Many POWs prayed to the Holy Infant for release and protection. Some of those who were able to return home, honored the Spanish advocation of the Christ Child by erecting a shrine to him.

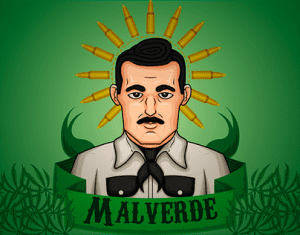

Jesus Malverde

Unlike the Holy Child of Atocha, Jesus Malverde is not an official Catholic saint. Some readers might have seen Jesús Malverde in AMC’s Breaking Bad. In an episode entitled “Negro y Azul,” a DEA agent who keeps a Malverde bust on his desk to “help him know his enemy” refers to him as the patron saint of drug dealers. Others might have tried the Mexican beer named in his honor. His latest appearance, was in the Brooklyn court where El Chapo Guzman, the father of Ovidio, was tried on multiple accounts of drug trafficking. One of Guzman’s attorneys claimed the 6 inch figure of the mustachioed Sinaloan folk saint “..miraculously appeared” in their court conference room the very day that former Sinaloa Cartel capo Jesús Zambada testified against El Chapo as a government witness.

In fiction and news media, Jesús Malverde is often depicted as simply the patron saint of drug traffickers, or el narcosantón. Such portrayals are simplistic, however. Absent from these representations are Malverde’s appeal to the poor, the sick, construction workers, and migrants. While he is more commonly known as as el narcosantón to outsiders, to his hundreds of thousands of devotees he is el ángel de los pobres, the angel of the poor.

According to legend, Jesús Malverde was born Jesús Juárez Mazo on December 24, 1870, just outside Culiacán, the state capital of Sinaloa. During Malverde’s youth, railroads arrived in Sinaloa bringing large-scale hacienda agriculture. He witnessed his community undergo rapid socioeconomic transformation. The profits of hacienda agriculture were enjoyed by the few elite, while the vast majority of the population, the peasantry, faced even greater economic strain. Jesús Malverde is said to have been a carpenter, tailor or railway worker. It was not until his parents died of either hunger or a curable disease (depending on the version of the story) that Jesús Malverde turned to a life of banditry.

Jesús Malverde earned a reputation as el bandido generoso, a generous bandit. Akin to Robin Hood in England, he was seen as a heroic outlaw who stole from the rich and distributed the plunder to the poor. In the most popular version of the Malverde legend, the governor of Sinaloa, Francisco Cañedo, personally challenged Malverde to steal either his sword or his daughter, promising that if successful he would be granted a pardon. According to lore, Malverde flitted through the governor’s mansion like a ghost, brazenly stealing Cañedo’s sword and leaving this message upon the wall: “Jesus M. was here.” Humiliated, the governor ordered him hanged with his arms tied behind his back. As a show of force, local authorities refused to allow Malverde to be buried and his body was left hanging until the bones fell to the ground. Over time, peasants threw small stones towards his remains as a sign of respect, eventually forming a rocky shroud over the bones.

The tragic death of Jesús Malverde is the salient aspect of his legend. Very little is known about Jesús Juárez Mazo, other than his execution in the year 1909. What is clear are the similarities shared between Malverde and two famous Sinaloan bandits, Heraclio Bernal and Felipe Bachomo. Malverde seems to be a synthesis of these two historical figures, while the execution of Jesús Juárez Mazo can be seen as the catalyst for the development of the folk devotion. His death at the hands of corrupt authorities appeals to the marginalized because they are vindicated through his victimization. Although the disenfranchised of Sinaloa lost a hero, they were compensated with a folk saint who has the power to work miracles on all fronts.

Most Malverde devotees are from the underclass of Sinaloa and northern Mexico. In the mustachioed saint they see a supernatural version of themselves. Alms collected at the Jesús Malverde Chapel in Culiacan– the most generous donations usually originating from the pockets of affluent drug barons- are often used to purchase wheelchairs and crutches for the handicapped, as well as for caskets for those who can’t afford them and even free breakfasts for hungry local children.

The folk saint began his debut as the patron saint of narcotraficantes in the 1970s, when Sinaloan drug baron Julio Escalante discovered that his son, Raymundo, was doing business with a rival cartel. He ordered sicarios to eliminate him. Raymundo Escalante was shot and disposed of in the sea. The dying man prayed fervently to Jesús Malverde for rescue. Seemingly miraculously, Escalante junior was rescued by a local fisherman and recovered from the shooting. He attributed his survival to the folk saint, whom, he stated had answered his prayers. However, it was in the 1980s and 90s as the Colombian drug cartels began to wither away and the Mexican drug cartels burgeoned, that the popularity of the Malverde cult skyrocketed. Through association with Jesús Malverde, the Sinaloa Cartel sought to vindicate the activities of their criminal enterprise. Investment in community infrastructure on the part of the drug gangs coupled with the government’s reputation as corrupt and absent contributed to this populist image.

It is advantageous for narcos to appear as though they are simple, faith-filled folk. Narco-dollars have brought more than jobs and infrastructure to Sinaloa. The influx of drug money to the cult of Malverde has led to burgeoning shrines across Mexico and even into the U.S. and Colombia, but the macho folk saint’s deepening ties to narco-culture has created serious problems for devotees. In many instances law enforcement on both sides of the border assume that Malverde images are an indicator of involvement with the drug trade.

Saint Jude Thaddeus

One of the most famous narco-saints, who is an official Catholic saint unlike Malverde, was practically unknown in Mexico before the 1980s. St. Jude Thaddeus has catapulted to the top position among saints in the country with the world’s second largest Catholic population. No other Catholic saint can rival the patron of lost causes. Only the Virgin of Guadalupe and folk saint Santa Muerte stand a chance of competing with St. Jude for Mexican souls. And over the past decade, competition between the nation’s number one Catholic saint and its top folk saint has become very intense, to the point that St. Jude in Mexico is now the only Catholic saint in the world who has a monthly feast day.

Until a decade ago, the green and white cloaked saint only had an annual feast day — October 28th — exactly like his thousands of fellow Catholic counterparts around the world. However, the unexpected emergence of Santa Muerte, a new grassroots saint personifying death, changed everything. Just a few miles down the road from the famous St. Jude shrine in Mexico City at the San Hipolito Church, Santa Muerte pioneer Enriqueta Romero (affectionately known as Doña Queta) has been holding a monthly rosary service dedicated to the skeleton saint.

What really stands out at the monthly fiestas attended by thousands, is the presence of marginalized Millennials, hundreds of whom huff glue and smoke marijuana on the sidewalks that abut the temple. Ironically, the saint who is depicted with the flame of the Holy Spirit on his forehead, has a reputation for healing drug abusers. In fact, this has been an important part of the ministry at San Hipolito Church, which now promotes a line of Saint Jude mineral water.

The strong contingent of marginalized youth and even criminals makes San Judas every bit as fascinating as the Bony Lady down the road. In theory, one of Santa Muerte’s strong appeals is that since she isn’t a Catholic saint some devotees feel freer in asking her for unsavory favors. However, it turns out that even though he is a canonized saint, St. Jude is also often asked to perform miracles that don’t square with Christian standards of morality.

This has become such a concern to the Catholic Church that in 2008 the Archdiocese of Mexico City released a statement warning against such unorthodox practices. One such heresy is the belief by more than a few devotees that when St. Jude is represented with the iconic staff in his left hand, he is open to prayers and petitions that he would never consider with the staff at his right.

Santa Muerte

Often featured on shrines beside Saint Jude, Santa Muerte is a skeletal folk saint whose cult has proliferated on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border over the past decade and a half. Some say that The Grim Reapress (she’s a female figure) has rapidly become one of the most popular and powerful folk saints on both the Mexican and American religious landscapes. Although condemned as demonic by both Catholic and Protestant churches, Saint Death appeals to millions in the Americas and beyond on the basis of her reputedly awesome supernatural powers. Devotees believe the Bony Lady to be the fastest and most efficacious miracle worker, and, as such, sales of her statuettes and votive candles now rival those of the Virgin of Guadalupe and the patron of lost causes, Saint Jude, the two other giants of the Mexican religious landscape.

On both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, the mass media have depicted her as the patron saint of drug traffickers. And sure enough, she plays an important role as protectress of peddlers of methamphetamines and opioids. DEA agents and Mexican law enforcement often find her altars at the safe houses of narcos. As an unofficial saint and one who represents death, ca va sans dire that she appeals to narcos. Supposedly, the most popular votive for drug dealers is the black candle, which is always inscribed with the ‘muerte contra mis enemigos‘ (death to my enemies). This candle may be lit for protection – both from rivals and from those who enforce the law – and for death and vengeance to enemies.

The saint accepts offerings, like other saints and folk saints, of flowers, fruits and other favorite foods, but also welcomes libations of tequila, oblations of marijuana and other drugs. Indeed, devotees are known not just for lighting cigarettes and huffing smoke at her, but also sharing their marijuana cigarettes with her. Her association with cartels has become so deeply ingrained in the Mexican administration’s mental map that President Felipe Calderon (2006-12) declared her religious enemy number one of the Mexican state. In March 2009, the Mexican army bulldozed dozens of her roadside shrines in the border cities of Tijuana, Nuevo Laredo, and Matamoros. The role of providing protection to narcos is just one of the many hats Saint Death wears as a multitasking miracle-worker. She is also a supernatural healer, love sorceress, money-maker, lawyer, and angel of death.

Juan Soldado

Juan Soldado is another folk saint who derives, like Jesus Malverde, from the legend of a local hero. Private Juan Castillo Morales was a young Mexican soldier. He served during a great period of unrest in Tijuana. Due to a new casino ban and the end of Prohibition, the numerous Americans who had once caroused in the city’s casinos and cantinas no longer came to the city. As a result the economy plummeted, unemployment soared and mass deportations of Mexicans from the U.S. exacerbated the situation. The final straw was when an 8-year-old girl was raped and murdered. The frenzied city exploded in furor.

The authorities seeking to quell the unrest arrested Private Juan Castillo Morales who was convicted of raping and murdering the girl without a proper trial, law enforcement failing to verify whether his fingerprints matched those as the crime-scene. The army executed him after a court-martial. They used la ley fuga (the law of flight). In this cruel ritual, the soldier was turned loose in a cemetery and told to run as fast as he could, while being targeted by a firing squad. He was told that if he made it out of the graveyard alive, he would be set free. Alas, he did not.

After his death, many of the poor in Tijuana decried his unfair trial, declaring that Juan was innocent and that he had been a scapegoat. The Private’s commanding officer, they claimed, had committed the crime and pinned it on the unassuming Juan to obfuscate his guilt. Numerous locals alleged that they saw blood oozing from Juan’s grave. On gloomy nights, they claimed they heard his melancholic voice resound amidst the tombstones of the cemetery. They began petitioning him for aid with their problems. A chapel was erected by locals, who turned to him for miracles and aid with their afflictions which he is said to have answered.

Since the establishment of his shrine, devotion to Juan Soldado, which means Juan the soldier, has mushroomed. Initially, Juan Soldado was unknown outside of Tijuana. But in the late 20th century, due to increasing violence in Mexico many sought to cross the border into the US to escape their circumstances and find safety abroad. Others, namely narcos, saw the border as an opportunity to enrich themselves via the drug trade.

When migrants and smugglers arrived in Tijuana many discovered Juan Soldado’s shrine and began venerating him for a safe crossing. If they made it across, and completed their perilous journey, they spread word of the miracle and thus disseminated devotion. This explains why Soldado’s following is particularly large in western Mexico, California and Arizona. Juan Soldado has not only become the folk saint of those seeking safe border crossings, which may involve drug smuggling, but also the saint of the undocumented and the falsely accused.

Kali Too

Of all the official canonized saints, St. Jude is the most popular in the drug trade. Many of those who engage in smuggling come from poor backgrounds, have few other opportunities and must deal with frequent catastrophes ranging from violence from rival cartels to frequent run-ins with law enforcement. They regularly petition the patron saint of desperation. Earlier this year, ICE agents found 233 pounds of marijuana rammed inside two plaster Saint Jude statues at the Reynosa-Hidalgo-McAllen international bridge. Devout Catholics were disgusted. The fact that many of Saint Jude’s followers pray to him for assistance in criminal enterprises is seen as even more of an outrage than asking the same thing of folk saints such as Jesús Malverde or Santa Muerte, given that they are perceived as heretical.

However, many narcos tend to be polytheistic, and on shrines discovered by the DEA and other authorities, officials often find more than one saint being venerated. Altars often feature a pantheon of saints being petitioned, even deities outside of Catholic traditions, such as Kali. No doubt this is because narcos believe that the more saints and deities they appeal to, the more likely their drug shipment will make it across the border and the more chance they have of staying alive and their enemies meeting a dismal fate.

*Dr. Kate Kingsbury obtained her doctorate in anthropology at the University of Oxford, where she also did her Mphil. Dr. Kingsbury is a polyglot fluent in English, French, Spanish. She is a polymath interested in exploring the intersections between anthropology, religious studies, philosophy, sociology and critical theory. Dr. Kingsbury is Adjunct Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada. She is fascinated by religious phenomena, not only in terms of their continuity across the Holocene and into the Anthropocene but equally interested in the changes wrought to praxis and belief by humans ensuring the infinite esemplasticity that is inherent to all religions, allowing for their inception, survival, alteration, regeneration and expansion across time and space. Dr. Kingsbury is a staunch believer in equal rights and the power of education to ameliorate global disparities. She also works pro bono for a non profit organisation that aims to empower and educate girls in Uganda. Follow Dr. Kingsbury on Twitter