Co-authored by Dr. Kate Kingsbury* and Dr. Andrew Chesnut

Santa Muerte, Saint Death and Holy Death in English, is now the fastest growing new religious movement in the West. There are no surveys of the number of devotees, but with 10 years of research experience, we estimate some 12 million followers, with 70% in Mexico, 15% in the U.S., 10% in Central America, and the remaining 5% mostly in South America. There are also small groups of devotees surfacing in Europe and other parts of the globe. Devotion to the skeleton saint only went public in 2001, so the great majority of adherents have become devoted to death only in the past decade and a half. In the U.S., devotees are concentrated in Texas, California and the Southwest, so it’s no coincidence that the first American Catholic bishops to condemn the Bony Lady (one of her common monikers) are from this region.

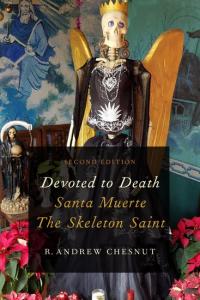

Saint Death is a skeletal folk saint whose cult has proliferated on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border over the past decade and a half. The Grim Reapress (she’s a female figure) has rapidly become one of the most popular and powerful folk saints on both the Mexican and American religious landscapes. Although condemned as demonic by both Catholic and Protestant churches, she appeals to millions in the Americas and beyond on the basis of her reputedly awesome supernatural powers. Devotees believe the Bony Lady to be the fastest and most efficacious miracle worker, and, as such, sales of her statuettes and votive candles now rival those of the Virgin of Guadalupe and the patron of lost causes, Saint Jude, the two other giants of the Mexican religious landscape.

On both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, the mass media have depicted her as the patron saint of drug traffickers. And sure enough, she plays an important role as protectress of peddlers of methamphetamines and opioids. DEA agents and Mexican law enforcement often find her altars at the safe houses of narcos. The administration of President Felipe Calderon (2006-12) even declared her religious enemy number one of the Mexican state. In March 2009, the Mexican army bulldozed dozens of her roadside shrines in the border cities of Tijuana, Nuevo Laredo, and Matamoros. But providing protection to narcos is just one of Saint Death’s multiple roles. She is also a supernatural healer, love sorceress, money-maker, lawyer, and angel of death.

In fact, the folk saint first emerged in anthropological records in the 1940s as a supernatural figure solicited by women seeking love sorcery. They sought the avenging death angel’s aid with returning wayward husbands.The oldest known prayer to the death saint consists of a petition requesting she use her scythe to bring back the straying husband, humbled at their wife’s feet. Today, the folk saint is still turned to for petitions of love and passion. Devotees typically use the red candle or red statuette of the saint for such amorous entreaties.

Color symbology and iconography are central to devotion. Santa Muerte is usually depicted with a scythe, a globe, sometimes the scales of justice and invariably an owl. The scythe is an iconographic vestige of her partly European heritage. It harkens to the Grim Reapress (la Parca), a medieval figure of death which the Spanish missionaries brought with them as part of their attempt to convert the Indigenous of Mexico to Christianity. It is the syncretism of the Spanish Grim Reapress with Indigenous beliefs in death deities, such as the Aztec goddess Mictecacihuatl, that gave birth to the Santa Muerte as we know her today.

The globe symbolizes Santa Muerte’s deathly dominion over the entire world and all those who inhabit it, for only she has the power to reap death. The scales of justice represent her ability to mete out justice for those who petition her to take their side in legal matters, disputes or any other similar concerns. Justice in this sense is a matter of perspective, typically associated with the devotee’s interpretation, and does not consist of a strict moral compass of right and wrong.The folk saint is essentially amoral, since it is believed if sufficiently supplicated she may take one’s side, even if one is requesting protection from the law or for her to use her scythe to wipe out one’s enemies in one fell swoop. The owl in Indigenous Mexican mythology is associated with death. Mexicans state that ‘when the owl screeches, the Indian dies’. As a syncretic symbol, the owl is also associated with knowledge and cognition in European folklore.

Color symbolism is also central to devotion and ritual. There are three main colors associated with Santa Muerte: red, white, and black. Interestingly, as academics we note that this color triad appears to be nearly universal across world religions for invoking the three main energies that humans seek to manipulate. The white statue or white votive candle in Santa Muerte devotion is used for blessing a venture, for cleansing, purification, and the removal of negative energy. Red, as has been already alluded to, is utilized for petitions related to love, passion, and lust. The black votive, or black statue, is notorious due to its nefarious associations.It is employed typically for black magic, vengeance, hexing and other such dark magical arts. For this reason it is rare to see it in a public shrine for most devotees seek to obfuscate their involvement in such activities. Nevertheless, Santa Muerte Negra, as the folk saint is known in this form, may also be used for more benign activities such as reversing spellwork, all forms of protection and removing energetic blockages. But it’s the rainbow-colored Seven Powers candle that best captures her broad appeal as many are looking for miracles on several fronts and not just one.

*Dr. Kate Kingsbury obtained her doctorate in anthropology at the University of Oxford, where she also did her Mphil. Dr. Kingsbury is a polyglot fluent in English, French, Spanish. She is a polymath interested in exploring the intersections between anthropology, religious studies, philosophy, sociology and critical theory. Dr. Kingsbury is Adjunct Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada. She is fascinated by religious phenomena, not only in terms of their continuity across the Holocene and into the Anthropocene but equally interested in the changes wrought to praxis and belief by humans ensuring the infinite esemplasticity that is inherent to all religions, allowing for their inception, survival, alteration, regeneration and expansion across time and space. Dr. Kingsbury is a staunch believer in equal rights and the power of education to ameliorate global disparities. She also works pro bono for a non profit organisation that aims to empower and educate girls in Uganda. Follow Dr. Kingsbury on Twitter