By guest contributor Dr. Alejandro Frigerio*

The sanctification of death and the similarity of their imagery often leads to confusion between the Argentine and the Mexican skeleton saints. However, there are significant differences between the two, due to the very different social contexts in which they developed and the different roles that “death” plays in the social imaginary of each society. Although nowadays there may be some overlap between the two devotions through the internet and social media, where it’s evident that some devotees may not clearly distinguish between them, they are two separate devotional traditions with significant differences.

I will highlight what I consider to be the most significant differences, without claiming this to be an exhaustive list, always keeping in mind that popular religious expressions are inevitably heterogeneous, so that evidence can always be found to contradict any attempt at generalization.

- Devotion to San La Muerte originated in Argentina, mainly in the northeastern provinces, especially in Corrientes (although it is also found in neighboring Paraguay). Devotion to Santa Muerte is Mexican, first appearing in the historical record in the 1790s worshiped by Chichimec Indigenous people in the present day state of Queretaro and Guanajuato.

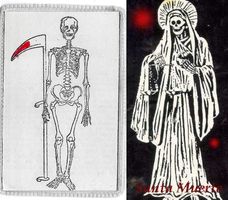

- San La Muerte is visualized as male while Santa Muerte is represented as female.

- The oldest images of San La Muerte show him as a squatting skeleton with his elbows resting on his knees and his hands supporting his head (in a version of SLM known as Lord of Patience) or as a standing skeleton holding a scythe. The most widely accepted historical image of Santa Muerte depicts her in a white robe, holding the globe of the earth in her left hand and a scale of justice in her right hand.

- The earliest mentions of San La Muerte (the first in 1917) refer to him as a “payé,” an object of power, rather than as a folk saint. This concept, of Guarani origin and perhaps influenced by African traditions, continues to influence religious practice. The idea of the “payé” is not present in the New Religious Movement of Santa Muerte.

- Due to its regional origin, which is scientifically documented and known by its followers, some differences can be observed between San La Muerte devotional traditions in its place of origin (Northeastern provinces of Argentina) and its spread in the greater Buenos Aires area and other regions of the country. In Mexico, while Santa Muerte was first mentioned as being worshiped by the Chichimecs today there is no attempt to remain faithful to that tradition. Rather, the current trend is to relate her to the Aztec death goddess, Mictecacihuatl.

- The images in the oldest and “traditional” altars of San La Muerte are small, less than 3 inches in size, often made of human bone, bullet lead, or hardwood. Images of Santa Muerte in the most prominent altars in Mexico are typically life-size skeletons, either real or very realistic representations.

- In more modern plaster images sold in Argentine santerías (botanicas), San La Muerte is depicted wearing a cloak and hood, and if the terrestrial globe is present, he is often depicted standing on it rather than holding it in his hands. Santa Muerte usually holds the terrestrial globe in her hand in most images but increasingly is depicted standing atop it, particularly in life-size effigies.

- Increasingly, devotees of San La Muerte believe that the saint had an earthly existence, that he was a virtuous Jesuit or Franciscan monk who cared for the sick during the time of the Jesuit missions. This belief mitigates the perception that he is “Death” and brings him closer to other models of Argentine folk saints. Santa Muerte is generally not believed to have had an earthly existence. The idea that she is “Death” is more explicit and unequivocal than in her Argentine counterpart.

- Devotion to San La Muerte is increasingly accompanied by devotion to Gauchito Gil (a social bandit turned folk saint). With the exception of a few old altars in rural areas, almost all current major San La Muerte shrines also have an altar to Gauchito Gil. The belief that Gauchito Gil was a devotee of San La Muerte is widespread. While devotion to Sinaloan folk saint, Jesus Malverde, sometimes accompanies devotion to Santa Muerte, the association between the two is not as close, and there is no legend or belief linking them.

- Despite the greater popularity of commercial plaster images, the practice of hand-carving images of San La Muerte remains alive, thanks to the work of a dozen or so carvers of the saint. Those made from human bone continue to be particularly prized. There is no recognized group of carvers for Santa Muerte.

- The smaller carvings, meant to be worn around the neck or carried, are still called “payés.” The term “payé” is foreign to the cult of La Santa Muerte.

- The practice of “embedding” the saint under the skin – by making an incision in the flesh and placing a small image of San La Muerte of one or two centimeters under the skin for protection – remains relevant. There is only one known specialist who performs this procedure, but it is in high demand among the saint’s most dedicated followers. There is no practice of “embedding” in the NRM of Santa Muerte.

- The ancient practice of blessing the images of San La Muerte still exists, although with different procedures, as nowadays they rarely involve the secret blessing in seven different churches. Images of La Santa Muerte are often “charged” by placing certain materials, such as mustard seeds and tiny horseshoes, in a hole at their base.

- It is very rare to find a life-size image of San La Muerte made from a human skeleton or a realistic imitation of one. Images of La Santa Muerte made from skeletons or their imitations are common in well-known shrines.

- During the celebrations of the saint, it is common to dance chamamé (a typical style of music from the province of Corrientes) as a way of paying tribute. Dancing is not as common with Santa Muerte although cumbias during her fiestas are on the rise.

- It is common for some devotees to dress as gauchos, especially at festivities in the less urbanized areas of Greater Buenos Aires, where chamamé is more commonly danced. Those who do this are probably migrants from Corrientes. There is no specific folk dress associated with Santa Muerte.

- It is almost an obligation for the followers of San La Muerte to attend the celebration of the saint on August 15 or 20 in one of the two most famous sanctuaries in Corrientes: the more traditional one in Empedrado and the newer and more spectacular one in Solari. This trip usually includes a visit to the Sanctuary of Gauchito Gil in Mercedes, in the same province. The most famous shrine to Santa Muerte, that of Doña Queta in Tepito, does not necessarily become an annual pilgrimage site for the saint.

- The annual celebration of San La Muerte takes place on August 15 or 20, and the Day of the Dead has little or no relation to the cult. Although originally unrelated, Day of the Dead, November 1 and 2, is becoming increasingly important in the worship of Santa Muerte.

- Traditional images of San La Muerte made of bone, wood, or metal did not wear a tunic. The more commercial and now more popular plaster images wear a black robe. Only in recent years have other tunic colors (such as red or white) begun to gain some sort of significance. For several years, the colors of the robes of Santa Muerte have been very significant regarding the types of miracles and favors each image specializes in.

- Media stigmatizations of the devotion to San La Muerte associate it more often with crimes and misdemeanors than with drug traffickers, who are not as prominent a social figure in Argentina. Stigmatizing images of Santa Muerte associate her with drug trafficking, and devotion is regularly reported on as part of narco-culture.

*Dr. Alejandro Frigerio received his PhD in Anthropology from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He is currently Tenured Researcher at the National Council for Scientific Research (CONICET) of Argentina and Professor in the Sociology Department of the Catholic University of Argentina as well as in the Graduate Program of the Social Anthropology Area of the Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Buenos Aires. He has researched the growth of New Religious Movements and Afro-Brazilian religions in the Southern Cone of South America for the last forty years.