Editor’s Note: another great post by The High Calling summer intern, Nathan Roberts

Bless me, Guardian, for I have sinned.

Just when you think we might’ve finally abolished that pesky notion of universal sin, The Guardian and The National Film Board of Canada are asking us to think again. On Monday, they released a fascinating collaborative project: “The Seven Deadly Digital Sins.” An “Interactive Reflection of our Digital Selves,” it’s a category-bending digital bricolage: part documentary film, part short essay collection, part survey, part infographic, all whirring bits of thought-provoking info.

The project centers around one major question: What does sin look like in the Internet Age? The “About” box explains: “Today’s digital world brings with it a whole new set of moral dilemmas… questions we need to ask ourselves. Not to do so would be a mistake; it might even be a sin.”

Choose A Sin

On the site, the leftmost column instructs us: “Choose A Sin.” The seven Deadlies are listed below. They structure a grab bag of testimonial content. Some bits are quiet and meditative, others satirically hilarious. (Gary Shteyngart’s video, filed under “Pride,” is a particularly biting treat.) Under “Envy,” Mary Walsh––equally thoughtful and funny––admits: “One in three people ends up being unhappier after spending some time on Facebook. I am that one person… People have better teeth, better children, better lives…. Better everything…. You are judging your insides by other people’s… curated outsides.”

Sometimes articles deal with sins in fairly traditional contexts. Baron asks: “I mean, let’s face it: where don’t you find lust online? Porn is there, like the way a mountain is there. And I climb it because its there.” On the subject of wrath, Jon Robinson explains the obvious: “There’s a dopamine rush that comes from being nasty. There’s a good feeling you get from realizing that you’re in a majority against a single person.”

But the project is at its most intriguing when it considers how sins look different online. We have sexual lusts, sure, but we also lust for attention on Twitter: “I’ve given up having a partner for sitting on my phone on Twitter at night,” shrugs Josie Long. And while food critic Marina O’Loughlin may not be gluttonous in a traditional sense, she wants to “consume” as many Instagram food pic likes as possible: “I can sulk… unattractively if the likes don’t come. I hate myself for it, but if it doesn’t pass the number eleven, when the likers are no longer listed by name, I’m as bad as any teenage girl.”

Participants differ in their moral convictions, but their contributions feel confessional and genuinely liberating––like long-repressed shames finally brought to light. The comedians are a nice touch, too. Their spoons of self-deprecating sugar help the medicine go down. The whole thing feels genuine, morally motivated, and compulsively readable/watchable.

As any Sunday School teacher will tell you, that’s an impressive triangulation.

“Sin” in the Structure?

With “Seven Digital Deadly Sins,” The Guardian and FBC are clearly trying to distance themselves from any regressive, anti-technology stances. “Watch, Read, Participate, Share,” the site encourages as it loads. It takes digital media seriously. The project doesn’t feel made in the spirit of Plato––venturing into the “digital cave” in order to help us, trapped technophiles, escape into the light––but Derrida, using digital structure (“the tools at hand”) to critique our digital lives. Executive Producer Loc Dao explains: “It was interesting creating a project that is so critical of how we live our digital lives while being so immersed in technology and design… We don’t feel a project succeeds unless the technology is complete with the story and form.”

With “Seven Digital Deadly Sins,” The Guardian and FBC are clearly trying to distance themselves from any regressive, anti-technology stances. “Watch, Read, Participate, Share,” the site encourages as it loads. It takes digital media seriously. The project doesn’t feel made in the spirit of Plato––venturing into the “digital cave” in order to help us, trapped technophiles, escape into the light––but Derrida, using digital structure (“the tools at hand”) to critique our digital lives. Executive Producer Loc Dao explains: “It was interesting creating a project that is so critical of how we live our digital lives while being so immersed in technology and design… We don’t feel a project succeeds unless the technology is complete with the story and form.”

While their thoughtfulness is evident, some stylistic choices seem better than others. The site exemplifies some of the problems it should probably critique. Stylistically, it’s a bit overbearing. Like Prezi, the interface is both seductively fluid and extremely busy. On the home page, data seems to float around in space without rhyme or reason. Sometimes illustrations upstage hard-to-read text. Nintendo 64 style MIDI music plays in the background consistently. It’s the sort of autoplay music that had us turning down the volume on Flash-based sites “way back when.”

I don’t mean to be overly critical, but the MIDI made me think of a bit from Zadie Smith’s seminal essay “Generation Why?”. Drawing from Jaron Lanier, she writes: “MIDI… takes no account of, say, the fluid line of a soprano’s coloratura; it is still the basis of most of the tinny music we hear every day…. simply because it became, in software terms, too big to fail, too big to change.” Smith’s beef is with Facebook: “when a human being becomes a set of data on a website like Facebook, he or she is reduced. Everything shrinks. Individual character. Friendships. Language. Sensibility.” When these reductive systems become “too big to fail,” Smith fears, our mental lives may be reduced to squeeze into their frameworks.

Does “The Seven Deadly Digital Sins,” such a creative, idea-driven website, reduce us? Actually, it seems to exemplify a more nuanced Internet Age paradox: it reduces and over-stimulates us at the same time.

Absolve or Condemn: Your Only Options

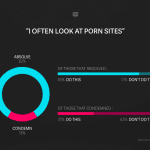

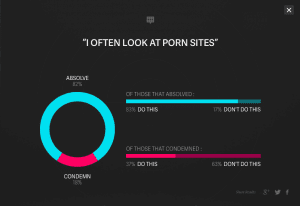

On one hand, the interactive survey portions gives us little wiggle room with our answers. First, we’re given lists of internet behaviors. Under Sloth: “I use Wikipedia instead of going to the library,” “I choose to text rather than to talk,” “I wish friends Happy Birthday on Facebook instead of calling.” Then we’re given two options: absolve the sins or condemn them. It makes for an interesting survey, especially because, after you make your choice, you’re required to admit: “I do this” or “I don’t do this.” Unsurprisingly, we’re more willing to absolve actions we do and more willing to condemn actions we avoid. (Currently, 82% of participants absolve looking at online pornography. Of those absolvers, 83% of them look at porn themselves.)

On one hand, the interactive survey portions gives us little wiggle room with our answers. First, we’re given lists of internet behaviors. Under Sloth: “I use Wikipedia instead of going to the library,” “I choose to text rather than to talk,” “I wish friends Happy Birthday on Facebook instead of calling.” Then we’re given two options: absolve the sins or condemn them. It makes for an interesting survey, especially because, after you make your choice, you’re required to admit: “I do this” or “I don’t do this.” Unsurprisingly, we’re more willing to absolve actions we do and more willing to condemn actions we avoid. (Currently, 82% of participants absolve looking at online pornography. Of those absolvers, 83% of them look at porn themselves.)

But there’s no place for context, dialogue, or back-and-forth discussion here. There’s no place for instruction or argument. It gets us thinking, and that’s a great place to start, but the reductive format suggests a postmodern approach to morality: I get to choose whether a sin is absolvable or not, alone at my computer, and what I choose is good for me. Thank you very much.

But it also opens up bigger questions. What could grace look like in a web-based structure? Our two options, absolution or condemnation, seem to echo the “Love it!/Hate it!” dichotomy that already flourishes on message boards and comment threads. Is this the only way? What could “hate the sin, love the sinner,” look like online? Or is the complex process of acknowledgement, confession, and forgiveness too complicated for a digital resource––even one as creative as this––to stimulate?

Over-stimulated, But Still Thinking

On the other hand, the site’s whirling, everywhere-at-once format appeals to our motion-loving eyes and our addiction to variety. It’s dynamic. It’s engaging. It’s overwhelming. And it doesn’t seem to cultivate the focused attention we need to really confront the issues at hand. After spending hours on the site, I like pressing buttons and seeing visual data fly around almost more than I like reading articles. This isn’t a problem, necessarily, but it does make me pause. Must we critique our narcissistic, ADD digital culture with an ADD-inducing website? Perhaps. Maybe that’s where we are, attention-span-wise. If we want to absorb data in flashy bits, at least we can make those bits worthwhile. (After all, this very article could be critiqued as just another “bit” in the fray.)

On the other hand, the site’s whirling, everywhere-at-once format appeals to our motion-loving eyes and our addiction to variety. It’s dynamic. It’s engaging. It’s overwhelming. And it doesn’t seem to cultivate the focused attention we need to really confront the issues at hand. After spending hours on the site, I like pressing buttons and seeing visual data fly around almost more than I like reading articles. This isn’t a problem, necessarily, but it does make me pause. Must we critique our narcissistic, ADD digital culture with an ADD-inducing website? Perhaps. Maybe that’s where we are, attention-span-wise. If we want to absorb data in flashy bits, at least we can make those bits worthwhile. (After all, this very article could be critiqued as just another “bit” in the fray.)

And these bits are worthwhile. While “The Seven Digital Deadly Sins” certainly isn’t an all-encompassing discourse on Internet Age morality, it’s an undeniably compelling conversation starter. The project dives in headfirst to address topics that we should start taking about more often. Its questions bleed off the screen and into our collective conscience.

Perhaps we should “Watch, Read, Participate, Share,” and then––crucially––use these bits of data to start our own conversations.

http://vimeo.com/97568526