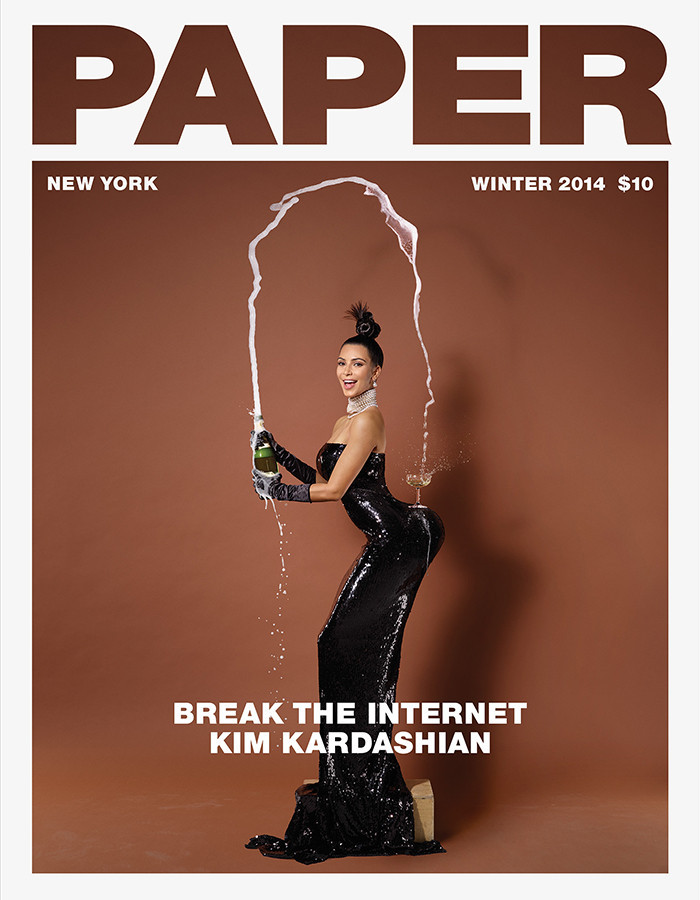

I have spent more time than I care to admit – by which I mean any time at all – looking at this photograph of Kim Kardashian and feeling annoyed. It took me a few moments of that time to figure out why, but here it is: I felt annoyed because I felt controlled, manipulated. And I didn’t like it.

Here’s the thing, in a photo, any photo, there are at least three “roles” we can take on. There’s the photographer, the one who took the shot, and then there’s the photographed thing or person or whatever. And there’s us, the viewers, the ones who look at it on the page. In every photograph there’s a game being played between these three roles, and I was annoyed at these pictures of Ms. Kardashian because I didn’t like what the role of viewer was doing to me. I didn’t like who I was being told to be.

***

A few days ago, in mid-morning, I celebrated mass with the young women of an all-girls Catholic high school. It was their “spirit week”, which meant that many of them arrived in their school chapel costumed. More practically, it meant that I found myself standing at the altar looking out at a buzzing congregation composed of painted KISS-mimics, crimp-haired Cyndi Laupers, and red-leather clad Michael Jackson imitators.

It’s a regular pleasure (whether it’s with a faux-Ace Frehley or not) to say mass, and the heartbeat of this pleasure is that I am allowed by the people of God to look at them from the perspective of God. What I mean is this: during most of the mass the priest speaks about God or to God, in the third person or the second person, but there are moments where the priest speaks as Jesus, in the first person voice of God, too.

Which means that while I’m standing at the altar, holding the bread and saying “this is my body”, the chalice and saying “this is my blood”, I get to, for a moment, stand in the place of God and look out at God’s people.

***

It was a week ago that Paper Magazine headlined its effort to “break the internet” with the aforementioned photographs of the ubiquitous Kim Kardashian in various stages of (un)dress.

Kim Kardashian herself needs little introduction. That this is true is verified by Amanda Fortini, writer of the few hundred words that accompany the photos (some of them nudes) of Ms. Kardashian. “If you know nothing else about Kim Kardashian,” she writes, “you know that she is very, very famous. Some would say that’s all you need to know.”

I do not know whether that is all I need to know, but I do know it’s not all I want to know. In particular there is one other thing I want to know, and it is this: what is looking at this photograph of Ms. Kardashian doing to me? Who are we told to be as we look?

We are told to be sexual. Just be possessed by your erotic desires. It’s a gaze of lust we’re asked to take on, a gaze that allows its vision to be narrowed until the only visible thing is Ms. Kardashian’s body and that body is only viewed as the object of a self-centered passion. If we look in this way we become nothing more a libido.[1. Consumerism tells us that “our bodies, like ourselves, are objects, packages, tools, and instruments. Commodification splits sexuality from selfhood. And sexuality… itself becomes a thing for exchange and price, a battleground for competition, a stage for aggression and self-infatuation. …The body is a commodity. The body is a thing.” (John Kavanaugh, SJ Following Christ in a Consumer Society, p13)]

We are told we are to be the objects of desire. After all, this is what your body should be. This is the gaze of shame we are asked to assume, the gaze that rebounds on us as we look with the judgment: you have been found wanting. If we look in this way we become people centrally aware of how far short we fall, of what we are not, and we are filled with shame in the recognition.

We are told to be powerful. If you had the capacity it would be you, not her, breaking the internet (or able to possess the one who is). This is the prideful and craving gaze, the gaze that sees in Ms. Kardashian only what she possess and we do not. When we look in this way we become Pelagians, constructors of a self-worth build on what we can control.

We are told to be callous. All your responses have already been expected and accounted for. This is the anesthetized gaze of the one who knows that the photograph is supposed to be “shocking” and “titillating” (whereas what would really be shocking is if we weren’t beyond being shocked). But when we learn to look callously it just means sinking into an ironic disdain, escaping into a comfortable numbness.

There are a thousand ways we can look at Ms. Kardashian’s photos, but in nearly every one we are all but forced to see her as an object. And every time we look at this object it looks back at us and recreates us in its image.

Another look is possible.

***

Yesterday morning, just after finishing my prayers, I watched a short film by a Dutch filmmaker, Frans Hofmeester. It is just four minutes long, and more of a timelapse portrait than a film, really. It’s built of hundreds of tiny, repeated clips, all of the same thing: Frans’s daughter, Lotte.

In them we see her, as Frans puts it, “grow up before our eyes” from the age of zero to fourteen. Mr. Hofmeester’s framing is steady, a consistent repeat of Lotte’s face, her eyes and shoulders, at times her hands. And, as we watch, she grows.

It’s the steadiness, the calmness in the fixed shot that mesmerizes. It’s the consistency of the perspective from which we watch her teeth poke through, and her eyebrows thicken. How we seem to stand before her as she learns to smile and to cry, plays with her hair, begins to talk, leans her chin forward in insistence. And, just as the eye of the camera is on her, so are hers on us.

We know it’s her father she is looking at as she sticks out her tongue, pouts, brushes her hair from her face. We know it’s him she is cajoling, speaking to, laughing with, that it’s him who’s asked to see her awards, her braces, her glasses, or the little flower barrettes resting in her hair.

We know, but she looks at us. And she asks, in the looking, that we look at her as he does, filling her up with loving admiration and amazement at her existence, pouring into her gratitude for the beauty that is her life.

And she tell us in turn: you too. You too, her eyes insist: like me, you too. All of us.

We are all of us the recipients of a love that sees in us such beauty.

— // —