Every Christmas growing up, my family would go caroling at the dairy farms that were about two miles upwind from us. In deference to the local Holstein inhabitants, we would always change the words of “The Friendly Beasts” appropriately: From

“I,” said the cow, all white and red

“I gave Him my manger for His bed

I gave Him my hay to pillow His head”

“I,” said the cow, all white and red

to

“I,” said the cow, all black and white

“I gave Him my manger for the night

I gave Him my hay to snuggle tight

“I,” said the cow, all black and white

Or something like that. The words kind of got changed a bit every year.

But is a song verse all the beasts get out of this? Does the incarnation only have meaning for us human animals?

I presume that most of us have been disavowed of the happy thought that Pope Francis said our pets are going to heaven. David Gibson gives us the blow-by-blow of the mistake, and shows how ridiculous things got, especially when the line “we will go to heaven with the animals” was attributed to St. Paul.

Jimmy Akin gives us the actual words of Pope Francis:

At the same time, Sacred Scripture teaches us that the fulfillment of this marvelous plan cannot but involve everything that surrounds us and came from the heart and mind of God… Hence, it is the new creation; it is not, therefore, the annihilation of the cosmos and of everything around us, but the bringing of all things into the fullness of being, of truth and of beauty.

And it would seem the story ends there. Our pets will not go to heaven; dairy cows have to rest content with a Christmas verse.

But then the real question arises: So Pope Francis didn’t say my dog is going to Heaven, fine… but is it? After all, one of the misattributions to Pope Francis is a quote from Pope Paul VI, explaining to a disconsolate little boy, “One day we will see our pets in the eternity of Christ.”

According to Jeff Schweitzer, Pope Francis has not thought about this very deeply:

Who among life’s menagerie will be admitted to heaven? I suspect the Pope did not think this through. For example, what exactly is meant by “all creatures” and “our animals”? Those two descriptors mean very different things; “creatures” is all inclusive, while “animals” excludes the other major life forms of plants, fungi, archaebacterial and bacteria.

He continues: “Face it; we all know that viruses, bacteria, plants and some animals like sponges are not going to heaven. And we know that because of our instinct for what it means to be intelligent, self-conscious and self-aware.”

For Schweitzer, the fact that we know viruses can’t “go to heaven” because they don’t have souls ought to help us recognize that the very concept of an immortal soul is fundamentally flawed:

Pope Benedict almost got it right when he said, “For other creatures, who are not called to eternity, death just means the end of existence on Earth.” He just needed to include one more species, humans, and he would be absolutely correct.

I would actually agree with Schweitzer all the way up to the very end. In some ways, he makes my argument for me. I agree with Schweitzer that the concept of an immortal soul is fundamentally flawed; flawed in the sense that the soul like the body is only capable of immortality because of the resurrection of Christ from the dead. There is no “natural” immortality for the human soul. Or as Karl Rahner explains:

From the perspective of a genuine anthropology of the concrete person, in this question we are neither justified nor obliged to split man into two “components” [body and soul] and to affirm this definitive validity [immortality] only for one of them. Our question about man’s definitive validity is completely identical with the question of his resurrection, whether the Greek and platonic tradition in church teaching sees this clearly or not (my emphasis).

And as he puts it elsewhere: “Matter for the Christian mind is not a watchword for a limited period but a fact in perfection itself (my emphasis).” In other words, it is the resurrection, not the immortality of the human soul freed of the body, that makes human beings capable of existing in eternal relationship with God. It is not our intelligence or even the fact that we are made in the image and likeness of God. These, while revealing a closer resemblance on our part to God than animals and other creatures, are not what get us into Heaven. What assures us of everlasting life with our God is the resurrection of Jesus from the dead. The entire discussion of resurrection in 1 Corinthians 15:36-49 is about “natural bodies” and “spiritual bodies.” There is nothing said about souls.

And so I respond to Jeff Schweitzer that “viruses, bacteria, plants and some animals like sponges” are indeed going to Heaven. And I would throw the burden of proof back onto those who says they are not. God is, after all the “Creator of Heaven and Earth,” and the Holy Spirit is “the Lord, the Giver of Life.” “You love all things that are,” Scripture explains, “and you hate nothing you have made” (Wis 11:24). Is his eternal love for everything he created not argument enough that all things will experience resurrection along with human beings? Let me explain briefly why and how.

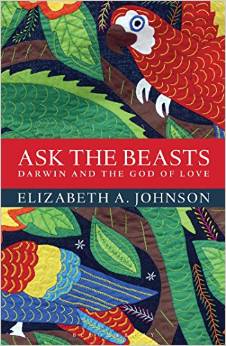

Why: Elizabeth Johnson has coined the term “deep resurrection” to reflect on the eschatological hope that exists for all of created reality. Johnson derives the term deep resurrection from the idea of “deep incarnation” put forward by Danish theologian Niels Gregersen. For Gregersen, St. John the Evangelists’ use of sarx (usually translated “flesh”) describes the incarnation in a far more extensive way than the language of soma (“body”) eventually adopted by the Council of Chalcedon (the Council that set the standard for how the Church still talks about the incarnation). John’s language draws on the Hebrew meaning of the term for which sarx is the Greek Septuagint translation, i.e., all physical reality. The flesh of Christ taken up in the incarnation, therefore, includes all of physical reality. Similarly for Johnson, deep resurrection, drawing upon deep incarnation, means precisely that in the resurrection of Christ’s physical body, all physical reality enjoys the promise of being raised. By taking on our “flesh,” Christ took on the reality of all created existence, and by rising from the dead, he offers the promise of resurrection, not only to self-conscious, conscious, or sentient beings, but to all created beings that have ever existed.

Why: Elizabeth Johnson has coined the term “deep resurrection” to reflect on the eschatological hope that exists for all of created reality. Johnson derives the term deep resurrection from the idea of “deep incarnation” put forward by Danish theologian Niels Gregersen. For Gregersen, St. John the Evangelists’ use of sarx (usually translated “flesh”) describes the incarnation in a far more extensive way than the language of soma (“body”) eventually adopted by the Council of Chalcedon (the Council that set the standard for how the Church still talks about the incarnation). John’s language draws on the Hebrew meaning of the term for which sarx is the Greek Septuagint translation, i.e., all physical reality. The flesh of Christ taken up in the incarnation, therefore, includes all of physical reality. Similarly for Johnson, deep resurrection, drawing upon deep incarnation, means precisely that in the resurrection of Christ’s physical body, all physical reality enjoys the promise of being raised. By taking on our “flesh,” Christ took on the reality of all created existence, and by rising from the dead, he offers the promise of resurrection, not only to self-conscious, conscious, or sentient beings, but to all created beings that have ever existed.

How: What about, for example, the Second Law of Thermodynamics decreeing the endless increase of entropy? What form will that take in the New Heaven and New Earth? The predator/prey relationship? Well, to be honest, of course we don’t know. But similar questions can be asked about what will happen to our own broken existences, and that doesn’t discourage us from hope. In the resurrection, nothing is lost, but everything is transformed. “The problem with transformation,” as theologian Anthony Kelly points out, “is that we cannot imagine what it means before it happens.” And so one of the foremost experts in the field of eschatology, Robert J. Russell, can only muse: “The New Creation will not include thermodynamics to the extent that it produces natural evils, though it might include it to the extent that it produces natural goods.”

What we do know, again from the book of Wisdom, is that God’s “imperishable spirit is in all things” (Wis 11:26). The implications of this are not that all things are innately immortal. Nothing is immortal. The implications are that this is so because “they are yours” (Wis 11:25). Because all things are his, all things will be resurrected and transformed. My dogs Sheila and Lily, my horses Josiah and Two Sox will all be there in the New Heaven and New Earth.

Now as for Mark Shea’s contention that the non-human universe may hope for eschatological transformation, but cannot experience salvation because it cannot sin, well, I have an answer for that in another post.