This is what authority looks like: like bowing and asking for a blessing.

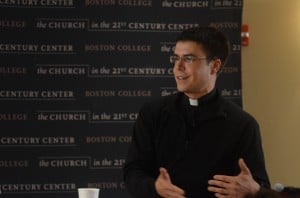

I woke this morning to this stunning image in my Facebook feed, courtesy of the Deacon’s Bench. As I’ve spent much of the morning driving back from seeing my family for Thanksgiving, it’s kept coming back to mind, as if it had something more to say.

The context for the photograph is Francis’s visit to Turkey, and meeting with Bartholomew, the Ecumenical Patriarch. In addition to being the first Sunday of Advent this year, November 30th is also the feast day of St. Andrew — the patron of the Ecumenical Patriarchate also named, in the Orthodox tradition, the “First-Called,” the disciple who encountered Jesus first and then brought his brother Simon Peter to meet the Lord.

And today, almost a thousand years after the schism between Rome and the East, the successor of Peter bowed before the successor of Andrew and asked for his blessing.

The first picture has been reminding me of this image as well, as Francis bowed and asked us all to pray for him after he was elected to the papacy.

This is how authority works: by telling people who they are and can become, much more than telling them what to do.

***

The East-West Schism began, among other reasons, over a crisis about how papal authority was supposed to work. And this image, and Francis’s bow before Bartholomew, helps us in the task — to which so much effort has been devoted since Vatican II, especially by John Paul II and Benedict XVI — of imagining how papal authority can more fully serve the unity of the Church.

Too often, when we talk about the Church, and especially about authority in the Church, we default to political models, where authority is a kind of force: the power to make someone else do something, or else. But in the life of the Church, authority is a kind of service, and it follows identity more than power, which is why we talk about the pope as “Peter” — not just abbreviating “successor of Peter,” but also saying who he is within the life and structure of our communion.

And, it seems to me, this is also how Francis exercises his authority — by helping us see who we are as Christians, as sinners redeemed by the merciful love of God, and as disciples called to the work of the kingdom. When he bowed on the balcony the day we met him, he told us that he needed our prayer, and therefore also that we were the ones whose prayer would be heard on high. His request for prayer allowed us to see and feel ourselves as the Body of Christ, to whose needs and service all the authority of the Bishop of Rome is oriented.

When he bowed today before Bartholomew, he told the world that this was a meeting of brothers, apostles together who cannot be who they are without each other. He told the world that the bonds of charity are deeper than, and the source of, the powers of office.

This is, perhaps, one of the most radical ideas that Christianity offers, and one that continues to come as a surprise to us, even long after we’ve first accepted the faith as true. Authority bows; power puts itself at the service of — is defined by being at the service of — the least of these.

When Francis bows, that’s what he’s showing us. And a few short weeks from now, when Advent has run its course, we’ll see what he’s been pointing to, when authority bows down into a manger again.