My work has been very heavily influenced by Fr. Alexander Schmemann and I think he has a great deal to say on the subjects of liturgy, sacraments, and the church.

For those of you who may not know him: Fr. Schmemann was a priest of Russian descent in the Orthodox Church committed to liturgical theology and renewal. After a teaching period in Paris (1946-1951), he joined the faculty at St. Vladimir’s Seminary in New York where he remained until his death in 1983. Married to Juliana, he was awarded the title of Protopresbyter, the highest accolade available for a married priest in the Orthodox tradition. His writings cover the liturgical life of Orthodox Christianity and call people to a deeper understanding of and participation in the church’s worship and sacraments. I don’t think it is a stretch to claim that Fr. Schmemann is to liturgical studies/theology what N. T. Wright is to New Testament studies.

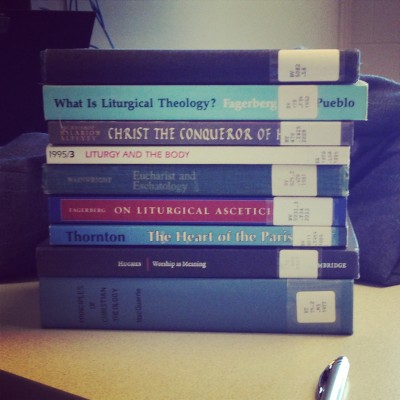

I am currently embarking on a new reading, researching, and writing project that will occupy a great deal of time. The overall goal of the project is to read through the important texts related to liturgical theology. Most of my time will be occupied by the writings of Schmemann, Kavanagh, Fagerberg, and Lathrop; the fruit of this reading will be seen through my blog posts, particularly “Sundays with Schmemann” and “Fridays with Fr. Kavanagh.”

Today’s content comes directly from Schmemann’s important work, Introduction to Liturgical Theology. In attempting to define the nature and work of liturgical theology, Schmemann writes:

“As its name indicates, liturgical theology is the elucidation of the meaning of worship…If liturgical theology stems from an understanding of worship as the public act of the Church, then its final goal will be to clarify and explain the connection between this act and the Church, i.e. to explain how the Church expresses and fulfills herself in this act.” – Schmemann, Introduction to Liturgical Theology, p. 17.

For Schmemann, the Church realizes that which she already is in the midst of the Eucharist. The Eucharist is the sacrament of the kingdom, the sacrament of sacraments, and through it she (the Church) shows the world the way the world was meant to be done. In worship, and therefore through the liturgy, the church gathers together for the corporate praise of Almighty God. She is fed by His word, the Word made flesh, and flesh and blood of the Word in sacramental mystery and revelation. A proper and robust understanding of worship’s words, gestures, forms, and meanings should therefore be taken as an utter priority within both the church and the academy. Fr. Schmemann felt so strongly about the importance of liturgical theology that he wrote, “Without liturgical theology our understanding of the Church’s faith and doctrine is bound to be incomplete,” (p. 19).

This can get confusing for some, as the purpose of research turns toward historical liturgical development and study rather than to theology. What is needed is a proper definition of terms and the goals in academic research. “Historical liturgics establishes the structures and their development, liturgical theology discovers their meaning: such is the general methodological principle of the task,” (p. 22).

In essence, we are arguing that the forms, patterns, and development of the church’s liturgy over the course of 2,000 is highly important but is incomplete. To really understand the meaning of her worship, to truly take seriously the Church’s theology-and-faith-in-motion, we ought to pay attention to the words she uses to praise God, in their liturgical context, and toward a specific end.

“From the establishment and interpretation of the basic structures of worship to an explanation of every possibly element, and then to an orderly theological synthesis of all this data–such a task is the method which liturgical theology uses to carry out its task, to translate what is expressed by the language of worship–its structures, its ceremonies, its texts and its whole ‘spirit’–into the language of theology, to make the liturgical experience of the Church again one of the life-giving sources of the knowledge of God,” (p. 23).

Such is the task of liturgical theology. Such is the goal of this blog. Such is my commitment to academic research and writing. I hope you stay along for the journey!