I remember it like it was yesterday: I was sitting in my freshman history class at George Mason High School and my teacher, Mr. Peloquin, was giving us a homework assignment. The assignment was simple. Actually, at the time I thought the assignment was stupid. We were to read through old political articles from the 1960’s and 70’s and make comments in the margins. That was it. We were supposed to write questions, comments, and other commentary on the pages provided us.

Now, I was neither the most diligent nor committed student in high school and college. Let’s be honest, I coasted through both based on my ability to memorize and pure, dumb luck. But for some reason I decided to give Mr. Peloquin’s assignment a try.

The first time I did this it was awkward. What should I write? Why does this even matter? My initial comments were shallow, surface deep. I had no idea what to write because I had no idea what I was reading. Looking back, it was like I was the young person at the table with adults trying to make way in a conversation about economics or religion. Nevertheless, I persisted. I realized after my first attempt that I was focused too much on the letter of the assignment rather than the spirit. You see, Mr. Peloquin wasn’t really trying to get us to mark up our books or articles for the sake of spilling ink (I abhor pencils and will therefore never spill lead). No, he was focused on helping us to read with comprehension, to engage with meaning, to participate in a conversation with passion.

Almost overnight I got the hang of the assignment and began to crave these articles. Why? Because I finally had a teacher who gave me a tool to learn. Reading these articles about Nixon, Ford, Carter, Vietnam, and more became an exciting exercise in knowledge acquisition and applied learning.

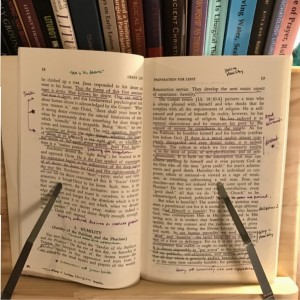

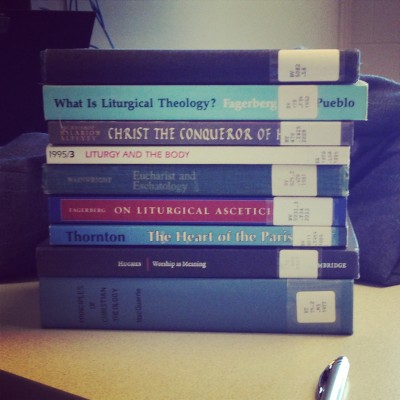

Ok, so why am I writing about this? Fast forward to today and flip through some of my books as I engage in my doctoral research. Nothing has changed for me. My books are coated with underlining, stars, asterisks, exclamation points, rebuttals, questions, comments, and much more. I am writing about this as a lighthearted plea for you to write in your books!

I don’t trust someone who won’t mark up a book. Even worse than the one who won’t write in a book is the one who has given up paper and binding books for e-books. That’s an entirely different post for an entirely different cup of coffee. I buy the majority of my books used and I’m always filled with joy when one comes my way and it is covered with notes and markings. Call in my learning style or call it neurosis–call it whatever you want!–but there is something tangibly powerful and a little mischievous about marring a perfectly crisp, white piece of paper for your own purposes.

Now, there has to be some sort of tie in to liturgy here, right? I mean, this blog is “The Liturgical Theologian” after all. Well, there’s not really a clear point here but I’ll make a stretch: one of the greatest Anglican Collects (a prayer meant to collect or gather the thoughts, praise, and prayer of the faithful) reads

Blessed Lord, who caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant us so to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life, which you have given us in our Savior Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Far be it from me to argue with Thomas Cranmer and the other Reformers. What if our reading of Scripture and our reading of other words became a way for us to learn through reading, marking, and inwardly digesting? What if we committed to mark up as many books as possible with as much ink as possible? No unblemished books left behind! No ink left unspilled! No pages left untouched!

* Yes, this blog post is both personal and entirely satirical. I still don’t trust you if you refuse to mark your books…