By now, most people have heard about President Trump’s meltdown yesterday at his eponymous tower. In a press conference that was supposed to address his infrastructure plans, Trump appeared to walk back his denunciation on Monday of white supremacists and neo-Nazis, claiming that there were some “very fine people” among their ranks. Predictably, this apologism for white supremacy, something that hasn’t been engaged in publically by a U.S. president since the days of Woodrow Wilson, sparked a firestorm of criticism. Business leaders, pundits, and politicians of all political persuasions condemned Trump’s pandering to advocates of hate, with some renewing calls for his impeachment or censure by Congress.

The spectacle of a U.S. president offering support to white supremacists got me thinking about my own experiences with racial animosity. As someone who was born and raised in rural Georgia, I’ve seen or heard my fair share of bigotry. An assistant principal at my high school, upon seeing my 9th grade history teacher with his black girlfriend, remarked that he was “dating a n*****.” A white girl in my 8th grade health class lamented that her cousin had fathered a “black baby.” My 8th grade Georgia History teacher trafficked in the myth that the Civil War was fought to preserve states’ rights, not to enshrine an economy based on the evil of human bondage. A number of my peers wore Dixie Outfitter apparel, clothing emblazoned with the Confederate battle flag, and my maternal grandfather wore such a hat to my high school graduation. That same grandfather almost constantly referred to African Americans by using the “n-word.”

Despite growing up surrounded by racial prejudice, my parents did their best to inoculate my siblings and me against such views. I can still recall examining a map of Africa, noticing the country of Nigeria, and asking my mother if that was where the word “n*****” came from. I’ll never forget the pain and outrage that flooded my mom’s face as she commanded me to never utter that slur again.

I also remember my parents, while on cross-country road trips to visit my dad’s family in Arizona, making a point of stopping at the Edmund Pettus Bridge to tell us about civil rights activists’ brave stand there on Bloody Sunday. On another such trip, they took us to the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, the site of MLK’s assassination, to impress upon us the horror of radical white terrorism. I recall my mother going to court to testify on behalf of a former black student of hers, ensuring that he wouldn’t be railroaded by a justice system that often prejudges young black men.

All these firsthand experiences drove home to me the importance of rejecting racial prejudice. But while my parents made it a point to indoctrinate me in the virtues of equality, I’ve often had mixed experiences with race and my religion, the Mormon Church.

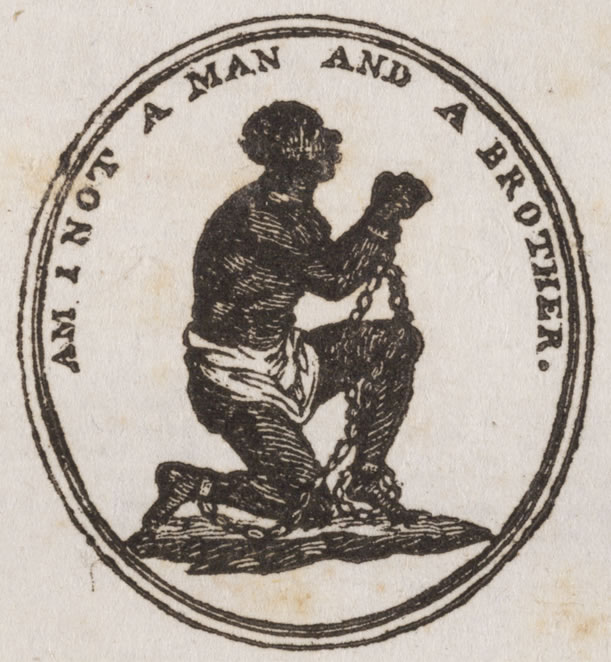

Mormonism has a convoluted, perplexing history with race. The faith was founded largely by people who hailed from New England and who tended to hold pro-abolition views. In fact, when the church’s first leader, Joseph Smith, embarked on a quixotic quest for the U.S. presidency, he proposed selling federally owned lands to finance the manumission of all the South’s slaves. Smith also expressed progressive racial views by endorsing the elevation of black men to Mormonism’s priesthood and allowing them to receive the sacraments of the LDS temple. Early Mormonism’s black-friendly leanings were even among the drivers of anti-Mormon persecution – as abolitionist Mormons settled in Missouri, a slave state, they inevitably rubbed their pro-slavery neighbors the wrong way.

But despite its early embrace of forward-looking racial views, Mormonism soon began a retreat in this regard. The faith’s second leader, Brigham Young, nursed racist views which, though not uncommon for his time, led him to deem blacks inferior to whites, to deny them the priesthood which Joseph Smith had given them, and to ban them from the Church’s temples. Young even went so far as to condemn interracial marriage as a sin, one which he suggested could only be expiated through the shedding of blood.

The legacy of Young’s racism would stain the LDS Church for over a century. Subsequent leaders, while not always subscribing to the more controversial of Young’s views, seemed to believe that his ban on black people receiving the priesthood was the will of God. They would try to justify this prohibition through a variety of shaky arguments – that Africans were descended from Cain, Adam’s cursed son, or that they had been neutral during the “War in Heaven” between Satan and God.

Over time, pressure grew on the Church to repudiate its priesthood ban, especially as thousands of people of African descent in West Africa and Brazil sought baptism into the faith. Black people already within the Church also lobbied Church leadership to change the policy, lamenting that their children, though raised in the faith, were leaving it because of its apparent racism. Eventually, in 1978, LDS Church President Spencer W. Kimball declared that he had received a revelation from God proclaiming that all worthy males would from that time forth be eligible to receive the priesthood, regardless of race.

While President Kimball’s 1978 announcement would end the priesthood ban, it couldn’t erase over a century of bad feelings surrounding the restriction and its misguided justifications. Many members, despite the doctrinal change, still clung to the old mythology surrounding the exclusion and still harbored prejudiced views of their black brother and sisters. Many LDS adherents also couldn’t shake the memory of the injustices that Church members had visited upon black people prior to the ban’s abolition.

Therein lies the conflicting experiences I’ve had with race and the Church. For example, I remember my paternal grandfather, a lifelong Mormon who served as a bishop, telling me about a negative incident that happened while he served in the Army in Fort Benning, GA. While there, he went out on the town one night with his friends, one of whom was Puerto Rican, possibly of African descent. They first went to a dance hall, where they were turned away due to the South’s Jim Crow laws. Disgusted, my grandfather had an idea. “Hey fellas,” he said, “I know someplace we can go where we can all have a good time.”

He then took them to an LDS meetinghouse where, he informed them, a dance for young singles was taking place. But when his multiethnic group of friends walked up to the building’s door, their way was barred by an older white man.

“You can come in here,” he said, pointing to my grandfather and the other white men who accompanied him, “but he can’t,” he finished, glaring fixedly at my grandpa’s Puerto Rican buddy.

My grandfather was, to say the least, infuriated. He stormed away from the building with his companions and refused to attend Church for a long time. Though he later found his way back to “the fold” and would serve in senior leadership positions in his congregations, he would always remember the indignity of the experience.

Decades later, my dad had a similar encounter with race and the Church. Fresh off of active-duty service in the Army’s 3rd Ranger Battalion, he, an Arizona native, had moved to my hometown of Cochran, GA, where he worked while waiting for my mom to return from her mission in Japan. While in Cochran, he was often asked to assist in blessing and distributing the sacrament (the Mormon equivalent of communion or the eucharist).

And that’s when it happened.

One Sunday, while preparing to distribute the bread and water used in the sacrament, an older white man (let’s call him Joe) approached him.

“Hello, Brother Ashcroft,” he said, “I don’t want you to pass the sacrament to those folks.”

My dad looked where Joe was pointing – his finger was directed at an African-American couple who had recently joined the Church and were sitting on a pew.

“Why not?”

“Because they’re black.”

My dad stared back at Joe, dumbfounded. Then he pointedly refused to follow the man’s advice and proceeded to give the sacrament to the black couple anyway. Later, as he related the story to me, he would note with a touch of schadenfreude that Joe had died from a massive stroke less than two weeks after the incident.

Although I’ve never had experiences in the Church like my father’s and grandfather’s, I have, unfortunately, witnessed prejudice among those who supposedly adhere to the Gospel. I particularly recall a time when a High Councilman (one of fifteen leaders over a Mormon diocese) said the n-word over the pulpit. Granted, he was trying to use it to illustrate the Parable of Good Samaritan (his exact words: “Imagine, the Samaritan was hated by the people in Judea – he was the equivalent of an ‘n-word,’ if you would permit me to use that dirty word”) but that’s no excuse. I also remember one of my professors at BYU citing statements by previous Church leaders discouraging interracial marriage. And of course, I had Sunday School teachers who trafficked in the same old discredited myths about the origins of the priesthood ban.

Again, this is why I say I’ve had mixed experiences with the Church and race. Don’t get me wrong – by and large, my experiences with race in the Church have been positive. My current congregation in Maryland is very ethnically diverse, with a sizeable population of African Americans, West African immigrants, and Haitian transplants. And growing up, despite what I’ve related above, I was regularly inundated with messages about the equality of God’s children and denunciations of racism. Even with the n-word-loving High Councilman referenced above, I distinctly remember the outrage that almost the entire congregation expressed about his statement – I believe he was subsequently relieved of his position.

But the fact remains that matters of race have not always been addressed in a proper manner in the LDS Church. At that is something that we, as Mormons, will continue to have to wrestle with, even as our nation endures the indignity of a President who finds common cause with neo-Nazis.