Many thanks to Jerry Shepherd for his previous essay, which defended Eternal Conscious Torment. We continue on with our dialogue on the duration of hell with this initial essay by Chris Date, who defends “Conditionalism,” otherwise known as “Annihilationism.”

INTRODUCTION

Eternal, immortal, resurrected life—albeit in torment. This is how most Christians have thought of the final fate of the unsaved, from

second-century Tatian to the Reformation’s Belgic Confession and through to today’s theologians like Wayne Grudem. This now-traditional view of hell is not one of disembodied spirits, but of resurrected, living people whom God has rendered immortal so as to endure physical and emotional torment for all eternity.

This view, however, has not always so dominated Christian thought. First-century Ignatius said the Lord suffered “that He might breathe immortality into His Church.” After all, “were He to reward us according to our works, we should cease to be.” Second-century Irenaeus was clear: life “is bestowed according to the grace of God,” and whereas the saved “shall receive also length of days for ever and ever,” the lost instead “deprives himself of continuance for ever and ever” and “shall justly not receive from Him length of days for ever and ever.”

Although this view was eventually eclipsed by what is now the traditional view, a growing number of conservative evangelicals promote it today as the doctrine of conditional immortality. According to this view, in the end God will grant immortality only to those who meet the condition of being united to Christ in faith. The risen lost will instead be annihilated: denied the gift of immortality, dispossessed of all life of any sort, and painfully executed, never to live again. And as Professor John Stackhouse boldly contends in the forthcoming second edition of Zondervan’s Four Views on Hell, this view “enjoys about as strong a warrant in Scripture as . . . any doctrine.”

#1: Scripture consistently teaches that the fate of the unsaved is to die, to perish, to be destroyed forever—in ways those words are ordinarily understood.

Peter says the reduction to ashes of Sodom and Gomorrah, and the extinction of their inhabitants, is an example of what awaits the ungodly (2 Peter 2:6; cf. Jude 7). He similarly compares the future fiery destruction of the wicked to those who perished in Noah’s flood (2 Peter 3:6–7). Jesus indicates that God will “destroy both soul and body in hell” (Matt 10:28; cf. Luke 12:4), using the Greek apollymi in the way it is consistently used in the synoptic gospels to emphatically say “slay” or “kill.” He elsewhere tells a parable in which weeds are burned up (Matt 13:30), the Greek katakaiō meaning to completely consume by fire. Jesus then interprets his parable, saying the wicked will likewise be thrown into a fiery furnace (vv. 40–42), alluding to Malachi’s prophecy that evildoers would one day be reduced to ashes beneath the feet of the righteous (Mal 4:1–3).

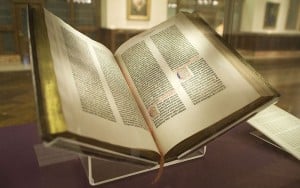

We have been trained—intentionally or unintentionally—to overlook the plain meaning of some of the most famous Bible verses. Paul says “the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom 6:23; emphasis added). Were the Greek thanatos not clear enough (it typically refers literally to death), Paul had already contrasted the free gift of life with the literal death that resulted from Adam’s sin and spread to all mankind (Rom 5:12–17). Jesus, too, says “God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16; emphasis added), the Greek apollymi meaning to die when used passively of human beings.

Overwhelmingly pervasive is the death and destruction language describing the final fate of the lost. Preston Sprinkle offers a mere sampling of such language, consisting of nearly fifty verses in the NT alone.

#2: Scripture consistently teaches that human beings are mortal and will not live forever unless God grants them immortality. This he will grant to the saved, but will withhold from the lost, who therefore will not live forever.

God had warned Adam that “in the day” he ate from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, he would die (Gen 2:17). The Hebrew phrase translated “in the day” often just means “when,” and needn’t be taken woodenly any more than when one says, “When you eat too much, you get fat.” Had God intended to emphasize that Adam’s death would take place immediately, he might have used the demonstrative pronoun: “in that day” (cf. Exod 13:8). Instead, when God carries out the sentence of which he had warned, that sentence is clearly literal death. Hence he says that “to dust you shall return” (Gen 3:19), and he evicts Adam and Eve from the garden so that they will not “live forever,” lacking access to the tree of life (Gen 3:22–23). So mankind fell into mortality; as Paul later writes, “sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men” (Rom 5:12).

Hope is not lost, however. Immortality can be sought and granted (Rom 2:7). The tree of life, which would have sustained the lives of Adam and Eve indefinitely, makes a reappearance at the other end of the Bible in the conclusion to John’s apocalyptic vision, where the saved—and they alone—enjoy its fruit (Rev 22:2). The significance of the imagery is perhaps clearer in earlier NT texts whose meaning is not so shrouded in symbolism: Paul says that resurrected believers will be rendered immortal, made fit to inherit God’s kingdom (1 Cor 15:50–55); Jesus himself says they, the sons of God, will be unable to die anymore, implying the lost will be able to die (Luke 20:35–36).

#3: Scripture consistently teaches that as a substitutionary atonement, Jesus suffered the wages of sin—death—in the place of his people. Those who reject his gift, therefore, will pay those wages themselves.

All orthodox views of the atonement include the element of substitution (penal or otherwise): Jesus took the place of sinners and suffered what they would have suffered, in their stead. That fate was death (Rom 5:6, 8; 1 Cor 15:1–4; 2 Cor 5:15). Were there any lingering suspicion that what Jesus suffered was anything other than literal death, Peter says he was “put to death in the flesh” (1 Pet 3:18; emphasis added), and the author of Hebrews says that what was offered was his body (Heb 10:10). Those who must suffer his fate themselves will therefore likewise die, rather than live forever.

#4: Proof-texts historically cited as support for eternal torment prove upon closer examination to be better support for conditional immortality and annihilationism.

Isaiah 66:24 says of the wicked, “their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched.” Alluded to by Jesus in Mark 9:48, this is often understood as meaning the fire will forever have fuel to burn, and that the worms will forever have food to eat. As that food and fuel, the living wicked will therefore be tormented forever, or so the reasoning goes. In reality, unquenchable fire burns up irresistibly (Ezek 20:47–48; Jer 17:27; Amos 5:6). So, too, undying worms and other unstoppable scavengers completely devour corpses (Deut 28:26; Jer 7:33).

Daniel is told only the righteous will be granted eternal life, whereas the unrighteous will be raised to “eternal contempt” (Dan 12:2)—the Hebrew dērāʾôn referring to something held in contempt by others, not to something felt by those who are themselves contemptible (cf. Isa 66:24). Jesus likewise limits “eternal life” to the righteous, suggesting that by “eternal punishment” he means eternal capital punishment—death forever (Matt 25:46). Paul confirms this conclusion, saying the wicked will pay the penalty of “eternal destruction” (2 Thess 1:9), alluding to Isaiah’s scene in which God’s enemies are slain and their corpses completely consumed. The phrases “eternal punishment” and “eternal destruction” do not imply ongoing activity any more than “eternal salvation” and “eternal redemption” imply ongoing saving or redeeming (Heb 5:9; 9:12).

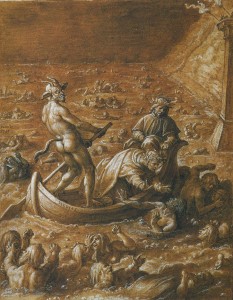

John’s apocalyptic, symbolic vision (Rev 14:9–11; 20:10) draws upon OT language and themes to communicate the final destruction of the lost: drinking God’s wrath (Job 21:20–21; Jer 25:15–33), fire, sulfur, and rising smoke (Gen 19:24, 28; Isa 34:9–10)—the latter of which is used elsewhere in John’s vision to predict the destruction of a city (18:7, 10, 15, 21; 19:3). John and God interpret the lake of fire imagery as symbolizing the “second death” of human beings (Rev 20:10, 14; 21:8), their inspired interpretation carrying more authority than that of anyone since.

CONCLUSION

Defenders of the traditional view of hell sometimes accuse its critics of being liberals caving into the spirit of the age, or at least of being driven by emotional sentimentalism to contort Scripture to fit a more palatable view of God and his wrath. In reality, following in the footsteps of early Christians like Ignatius and Irenaeus is an increasing number of evangelicals who, as J. I. Packer said of “honored fellow-evangelicals” John Stott and John Wenham, embrace conditional immortality and annihilationism “for the right reason—not because it fitted into their comfort zone, though it did, but because they thought they found it in the Bible.”

The Bible consistently teaches that the lost will finally die, perish, and be destroyed. It teaches that immortality is a gift God will grant only to the saved. It teaches that the Lord died a vicarious, substitutionary death in the place of those who accept it, implying those who reject it will suffer that fate themselves. And the Bible nowhere teaches that the unsaved will instead be made immortal to endure eternal life in torment.