The Pagan community pays more than occasional lip service to the idea that modern Western Paganism is orthopractic, rather than orthodoctic. The underlying problem is that it’s not really either.

Even at a glance, we can be certain that Paganism(1) isn’t hung up on orthodoxy. That much is clear from even a brief look. But then we try to apply the opposing concept: orthopraxy. This is an attempt to understand Paganism within the preexisting framework of Western religion.

Despite its occasional forays of belief into the territory of transcendent religions, one of the things that Western Paganism brings to the table is its conception of immanence. Rather than deities that are wholly outside of the world (transcending it), we have deities and practices that are spiritual and yet intimately involved with the world in which we live.

For the everyday person, transcendence and immanence are more trends of thought than explicit rules of belief. It’s not that the average Pagan thinks about how the gods and the world of the spirit are immanent. We just function that way.

Where the common Western view of religion is that the miracles are generally in the past or the future, for the Pagan community, it’s here and now. And while such event are impressive, our miracles are hardly considered miraculous.

Neither Orthodoxy nor Orthopraxy

Certainly some Pagans believe in the transcendent. We occasionally hear claims about how the gods are all-powerful, for instance. However, any religion that values magic, deals with a downright pragmatic immanent spirituality, and knows that the miracles aren’t a promise for tomorrow can’t rightly be called transcendent.

The categories of orthodoctic or orthopractic religions are better suited to understanding transcendent religions. If we were going to sum it up in a couple of words, “orthodoxy” is about “right belief.” It is often, in the Pagan world, held in contrast to orthopraxy or “right action.”

That seems to fit nicely. At first glance Paganism, in contrast with our (mostly) Christian heritage, doesn’t so much care what you believe as what you do. If bumper stickers with nine-letter words every got popular, we could get a bunch made that say “Orthopraxy, not Orthodoxy.”

Unfortunately, it’s still a bumper-sticker solution to a deep problem. In order to hold true to this binary opposition, we either need to define “action” in ways that are extremely broad, or we need to reduce our behaviors to their mechanical components.

The idea that Pagan religion is involved in “right action” doesn’t hold much water. We could just as easily redefine Paganism as “right awareness” or “right membership” or “right relation.” I would go so far as to say “right pragmatic, immanent awareness and action.” Sadly, if I tried to put all of that on a bumper sticker, people would constantly drive into my car trying to read it.

There are religions out there that are, in fact, orthopractic. To see a “real” orthopraxy, it would be more appropriate to look at maybe Shinto, or even a number of the more spiritual martial arts. These are practices that prescribe actions in the “real world” sense.(2)

What Paganism (including Wicca) does seem to have in common is a different ortho-something. It’s not right belief, or right action, so much as it is right-relationship, or “harmony.”

This isn’t the transcendent New Age harmony of being at one with the universe, but more of an Immanent harmony of being at one with reality as it really is, all around us and right now.

What does Immanent Religion Look Like?

I just read a piece by Sarah Wreck over on Disinformation titled, “Noise Guy Calls Out Empath on Her Bullshit”. It’s a really good piece to read if you have any interest in the actual application of magical ethics or consider yourself sensitive (and yet not sensitive to foul language).

You see, the author isn’t just super-sensitive, she considers herself a sensitive. If I’m understanding, it’s not just something she does, it’s a defining part of her identity. Which means that her sensitivity is a part of pretty much every situation in which she finds herself.(3)

To summarize Sarah’s piece: she was at Kansas City Noise Fest. After a set, Noise Guy came up to talk to her, and she casually went into empath mode.

Noise Guy called her on it. He set boundaries. They had a pleasant conversation, and they both moved on with life. What’s interesting is that he recognized her for what she was and insisted on an equal sharing. He didn’t spook; he didn’t freak. And he didn’t compete.

How was Noise Guy able to do this? That’s not part of the story. And I suppose it doesn’t really matter how.

Overall, it is an interesting and useful piece in a number of ways. But the most useful thing that I took away from it was that Noise Guy, whoever he is, is perhaps the new face of an American Paganism.

What’s that? Where did I get that idea? Because at the end of the day, Noise Guy took the spiritual world in stride. This is what immanent spirituality really looks like. It’s not so much “O.M.G. you’re Magickkkkal!” as “yeah, yeah, we’re all magical, now are you gonna take care of that?”

When we make the switch from transcendent religion where the fruit is forever out of reach, to immanent religion where we end up making jam all day, we discover that the fruit isn’t always perfect. We learn that making jam is repetitive, sometimes boring, and definitely hard work.

The interesting thing about immanent spirituality is that it is neither based on “right action” or “right belief” (orthopraxy and orthodoxy) in any but the broadest senses. It is based almost entirely on praxis. Or, to put it less gently, “whatever works.”

Whether we use the family recipe, take classes in jam-making, or just plain experiment until we get a flavor we like, what matters isn’t the process. What matters is the product.

Doxis, Praxis, and the Way Forward

At first glance, orthodoxy and orthopraxy form a nice, tight binary opposition. Using this tool of analysis, religions are considered one, the other, or something in between. But Paganism is neither fish nor fowl. At its best, Paganism follows a trajectory that ignores the binary. This is how it should be.

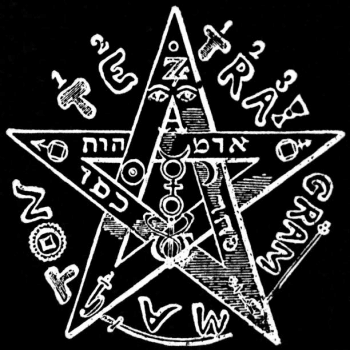

The use of orthodoxy and orthopraxy as terms of analysis are tied to the use of the root “ortho-“ meaning “straight” (Greek) and implying in their use “right” or “correct” (viz. right belief vs. right action). But the idea is really tied to conceptions of correctness and being on the correct path.

Binary oppositions form a significant portion of how we think about the world. They include patterns of thought such as true and false, correct and incorrect, straight and crooked, and right and wrong. But these are not things; they are ways of talking about things. When we say that Paganism is orthopractic, that it is based on “right action,” we buy into the idea that there is a “correct” way and that the way to understand it is through words.

But in the philosophical jungle that is the West, we end up finding that any concept of right and wrong ends up resting on some kind of infinite authority of Neoplatonic origin. It’s just how we use words.(4)

It gets worse, though. In the analysis of praxis (action) and doxis (belief), Paganism has little orthopraxy and even less orthodoxy. While Christian conceptions of orthopraxy involve good works, right living, and ritualism, Western Paganism focuses on ritualism and mostly ignores the other two.(5)

But if immanent spirituality is such a good fit for much of Paganism, why are we so interested in taking up the trappings of a transcendent religion?

Our Judeo-Christian Heritage, Materialist Positivism, and Progress

Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live, they say. It is ingrained deep in our culture that anyone who has hidden power is up to no good. The fact that magic is less powerful than a law degree, less useful than a CPA, and (if you do it right) more work than an M.D. – all while failing to come with dental or even a pension plan – seems to escape the rumormongers of the West.

There are some few of us who struggle to cultivate our own spirits. We stand outside the everyday world, and live without swearing our souls to some universal (and yet also seemingly mundane) hierarchy. From the outside, most of us are pretty uninteresting. But no matter what we do, we still get the stink eye.

What terrible things do we do? We dare to understand our own spiritual natures. We try to understand the nature of the world around us. We throw off the yokes with which they would bind us to what they would call harmlessness, but is closer in truth to powerlessness.

The Chains That Would Bind Us

The everyday Westerner has been taught one of two things about the nature of the human spirit. Both are equally reductionist, useless, and disempowering.

The first terrible idea is the idea that the human spirit is some glorious thing. This is the conceit of the modern Judeo-Christian tradition. It comes from an inability to linguistically distinguish between classes of spiritual experience.(6) There’s no good way for your average Christian to distinguish a spiritual experience from a sacred one. Christians can tell the difference as well as anyone else, but the average believer doesn’t have the language to talk about it.

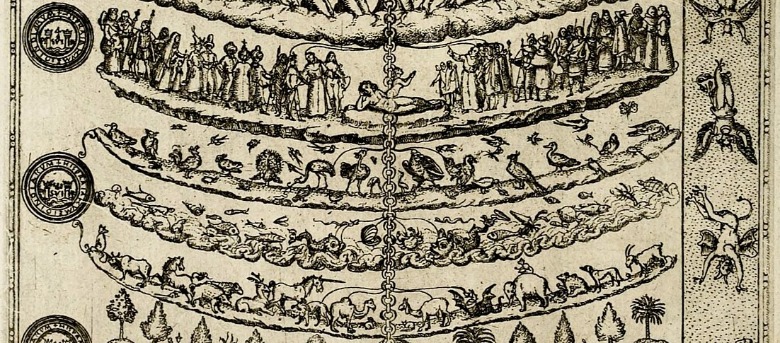

Once upon a time, there was a Christian language to talk about this. Everything in the universe was put on a scale from God to mundanity. This was the Great Chain of Being, and it works pretty well if you’re a monotheist.

When this lack of a relevant language is combined with a conservative reliance on past knowledge, there isn’t a lot of room in Christianity for the same type of spiritual growth and understanding we find in Western Paganism. In fact, most sects have rules against it.(7)

The second idea that would chain us exists in counterpoint to the first. The materialist positivist approach, used in science, discounts the spiritual as irrelevant to their study. As science has increased in social status over the past four centuries, it has become somewhat fashionable to apply this tool of analysis not just to scientific research, but to every aspect of life.

Materialist positivism holds to the idea that the human spirit doesn’t exist at all. “Magical” experiences are described as nothing more than epiphenomena that fools think they experience because they don’t accept that they’re no more than a meat-body.

Such a position lives in uneasy harmony with the transcendent approach of the Judeo-Christian tradition. Their common ground is that the immanently spiritual is either suspect or fraudulent. But the immanently spiritual is our territory. Western Paganism lives in the crevice between these two flailing giants.

ProTip: For all that I am a fan of immanent spirituality, there are dangers. Beware of prosperity theology, whether it comes cloaked in Christianity, Neoplatonism, or just plain New Age fascism.(8)

Prosperity theology is any practice that draws a one-to-one correspondence between one’s spiritual wellbeing and material health and success. It’s the spiritual equivalent of blaming the victim. It’s bad theology, and it’s mean.

Spiritual strength, flexibility, and health are all things that can improve our lives. And these are all true Pagan values. But any path that promises to insulate us wholly from the realities of being human – from everyday bad luck to inevitable death – is playing you for a sucker. At best, the leaders are lying to themselves. At worst, they’re true believers led down the wrong path by their own mentors.

Neither Orthodoctic nor Orthopractic

When it comes down to it, the bulk of Western Paganism is neither orthopractic nor orthodoctic. It is neither wholly “religion” in any traditional sense, or wholly “science.” It’s a classification of knowledge doesn’t quite fit the Western model because it recognizes an immanent spirit that is part of everyday life.

Whether it’s card reading, empathy, or straight-up magic, we Pagans live (or at least seek to live) in a world that is rich in spirit. There are few promises of eternal life. Our spirituality exists in the same world as death and taxes, and makes no promise to free us from either. Perhaps our “miracles” are prosaic, but they’re here and now. And that’s enough for me.

NOTES

(1) Paganism is defined here, somewhat circularly, as the breadth and depth of “religious” activity in which people self-identified and in many cases identified by their communities as Pagans take part. It may also include a number of associated groups that may or may not self-identify on a case-by-case basis.

(2) There is a place for straight-up orthopraxy. If you’re ever been serious about the martial arts, or lived in East Asia, you might well be familiar with the level of perfection that goes so deep that it becomes something spiritual. From the tea ceremony to flower arranging to drawing a sword, there is a depth to these practices that brings out an inherent, beyond utilitarian, value.

(3) I’m making some assumptions about the author based on being a long-time reader of her Shitty Occult Comics.

(4) The only way out of this, in my experience, is to “cross the abyss” (by one name or another). It is only by doing so that we can collapse the binaries that necessarily arise when we look out from out limited perspective at a larger universe.

(5) When Paganism does focus on good works and right living, it’s usually borrowing popular political concepts. Since the 70s, that has mostly been left-leaning politics from the ecology movement and feminism. The “right action” of Paganism merges nicely with some of the trappings (a female aspect of divinity, for instance, or a love of the Earth), but is only loosely emergent from its cosmology. It is just as likely that our politics shape our religious beliefs and actions as the other way around.

(6) That’s not to say that Christians lack the ability to attain spiritual growth. They can, and do. But that growth looks very different from what a Pagan’s spiritual growth looks like. If we combine the worldview of the Christians with the practicality of the Pagans, we get something that looks like Prosperity Gospel. See the ProTip for details.

(7) YMMV on individual practitioners. I have known a few Christians fully capable of straddling the immanent/transcendent line. I’m talking about basic theology here, not every Christian ever.

(8) For the quintessential example of this, take a look at Carlos Castaneda’s cult, where he was unable to admit his cancer because he’s made promises as a teacher that his practices would insulate his followers from such things.