In his book, The End of Religion, Bruxy Cavey made this statement about faith,

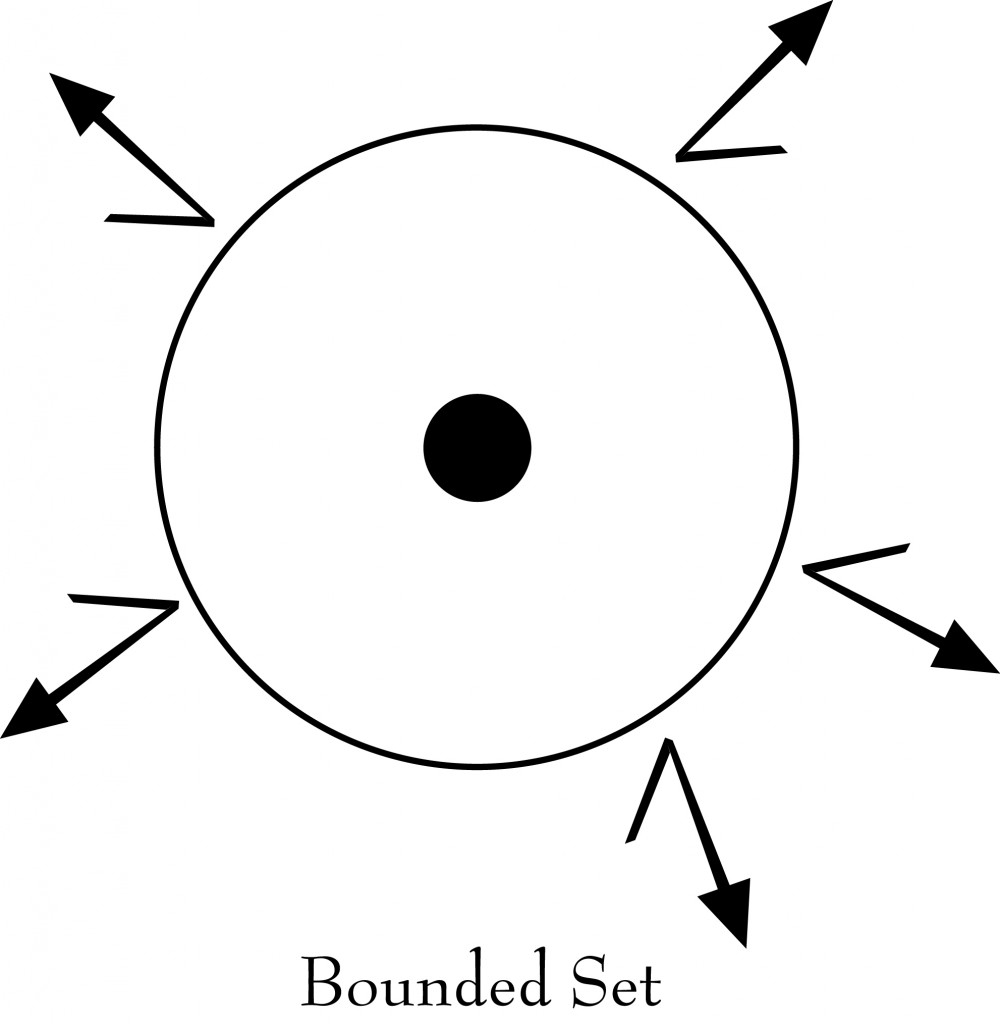

“When faith becomes religion, people on the inside of the group begin to focus their attention on the perimeter, patrolling the boundaries to regulate who is in and who is out. They develop visible boundary markers, demarcations of holiness, which become important signs of group identity” (p. 212).

This statement echoes my own in so many ways, especially as it relates to Evangelicalism.

In fact, Evangelicals are often more concerned with maintaining membership based on strict adherence to a well-defined doctrinal code. If an individual does not hold to one of the pre-determined ‘essential’ doctrines, they are outside the circle and their membership rights revoked.

However, there are many problems with this set-up.

For instance, Who sets the perimeters? Who determines what doctrines are essential and non-essential? And, on what basis? As Roger Olson has often asked, is there an evangelical magisterium? The answer is, no.

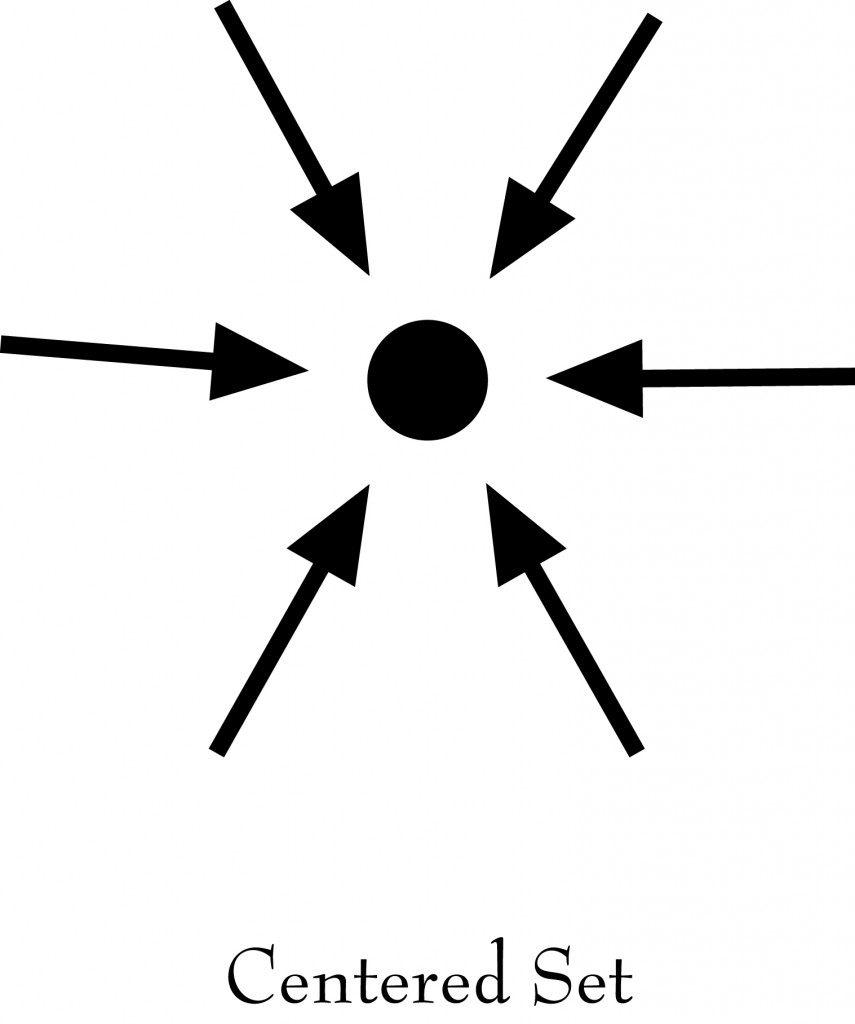

A Center Does Not Indicate a Circumference

Having a center point does not also include the need for a circumference. A circle will indeed have a center, but no one ever claimed that evangelicalism is a circle, only that it has a center, and that the center point is illustrative of those beliefs we hold to be of greatest importance.

A boundary is not necessary in such a context. In this scenario, one is considered ‘more’ evangelical by their closeness to the center; by their belief in and relationship to those ideas considered significant by the majority of those underneath the tent. There will no doubt be variety in the details of some of those beliefs, but enough of the core is maintained to establish ones position to the center. Ones distance from the center is dependent on their relationship to core beliefs.

As Olson and others have pointed out, who determines what these core beliefs are exactly? While some may consider a certain set of beliefs to be of central significance, others will no doubt hold to a slightly different set. Context plays a significant role here. Methodists may aspire to maintain entire sanctification, while Pentecostals may wish to emphasize Spirit baptism.

Someone once said that theology is a matter of emphasis. If this is true, then what one particular group emphasizes in their theological systems is deemed to be of special significance to them, and therefore worthy of being held close to their center.

With this in mind, I’ll ask the question again: who determines what beliefs are core and which ones should be moved a little further away from it? If evangelicalism does not have a central ruling magisterium, as Roger Olson and others have stated, who makes the decision as to what constitutes core and peripheral doctrines? If that right has not been given to one group (and it hasn’t), then who decides? Neither the Open Theists, Arminians, or Calvinists. All three have to in some way or another contribute to the discussion. Each group should have an equal voice at the table. In this type of scenario, a degree of theological hospitality has to be given by each voice, as each also recognizes and appreciates the theological emphases of the other.

In the end, we as evangelicals get to decide. Not Arminian evangelicals, or Calvinist evangelicals, or otherwise. No one group has been appointed as the official spokesperson and theological determining body. For a group to assume such a role, for whatever reason, would be a prideful and arrogant tactic. It reminds me of the question posed to Jesus about who is the greatest in the kingdom of God! His response was, ‘certainly not those who assert themselves to the front of the line.’ We refer to that move as incredibly rude.

The center of evangelicalism is determined by us – those who call this place home. There will be some degree of theological variety because of our varied emphases, but it is possible to gather around those things we hold in common and are deemed to be of greatest significance. On those areas where we differ, we continue to discuss them in a spirit of charity and grace, realizing that we are all en route and equally need increasing clarity for the journey ahead.

I need my Calvinist family, just as much as I need my Openness relatives. Like a family, there will be disagreements, but we don’t disown members for disagreeing with one another. No, we take the time to listen more attentively and love each other anyway, despite our differences. For those who differ more greatly than others, we love even more; in the hope that love will eventually bring them closer to home, the center of a family’s existence.

———————————————————————————————————-

Jeff K. Clarke is a blogger and an award-winning writer of articles and book reviews in a variety of faith-based publications. Blog: http://jeffkclarke.com/, Twitter: www.twitter.com/jeffkclarke, Facebook: www.facebook.com/jeffkclarke