“Here his mighty waters play On the organ all the day”

Thus did John Keats describe his visit to the Isle of Staffa and its redoubtable feature, Fingal’s Cave, a huge chamber hollowed out by the unimaginable power of the sea over vast stretches of time. For millennia those pounding waters have created a vast cavern that resounds like the largest pipes of a natural organ, as Keats described it so well. Even as I write, I can faintly hear the eerie sound of that cave, though my visit was some 15 years ago.

I made the visit in a small ferry from the Island of Mull, traversing the six miles in a quite choppy sea, accompanied by a group of German tourists who had walked (!) from east to west right across the whole width of Scotland at one of its widest points, a journey of about 225 miles. Unlike many Germans, few of them spoke much English, so I, in my less than perfect Deutsch, engaged one or two in halting conversation. Our dialogue was made no easier by the whipping winds and bucking boat, but we did as best we could, laughing through our rudimentary linguistic skills. After a few pleasantries about homes and families had nearly exhausted my store of German nouns, we nearly simultaneously began to sing the very catchy tune of Felix Mendelssohn’s “Hebrides Overture,” sometimes known as “Fingal’s Cave.” It begins with a rocking tune in the lower strings of the orchestra, for all the world a rich and near exact echo of the rolling waves on which we now were gliding. I am a trained singer, while many of my companions were more of the bathtub variety of vocalist, but nearly all on the ship joined in with might and mane, our twenty or so voices booming through the wind.

I made the visit in a small ferry from the Island of Mull, traversing the six miles in a quite choppy sea, accompanied by a group of German tourists who had walked (!) from east to west right across the whole width of Scotland at one of its widest points, a journey of about 225 miles. Unlike many Germans, few of them spoke much English, so I, in my less than perfect Deutsch, engaged one or two in halting conversation. Our dialogue was made no easier by the whipping winds and bucking boat, but we did as best we could, laughing through our rudimentary linguistic skills. After a few pleasantries about homes and families had nearly exhausted my store of German nouns, we nearly simultaneously began to sing the very catchy tune of Felix Mendelssohn’s “Hebrides Overture,” sometimes known as “Fingal’s Cave.” It begins with a rocking tune in the lower strings of the orchestra, for all the world a rich and near exact echo of the rolling waves on which we now were gliding. I am a trained singer, while many of my companions were more of the bathtub variety of vocalist, but nearly all on the ship joined in with might and mane, our twenty or so voices booming through the wind.

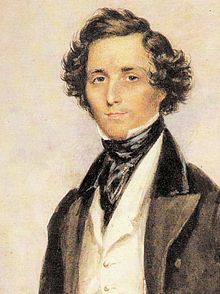

Mendelssohn after all was one of their own, son of a very wealthy Berlin businessman and grandson of one of the greatest Jewish thinkers of the 18th century. Felix Mendelssohn was without doubt one of history’s most remarkable musical prodigies, playing piano and violin well before he was five, writing string symphonies still heard today before he was ten, astounding audiences with improvisational gifts from Germany to England, even becoming a favorite of Queen Victoria who delighted in his visits. During one of those trips, the now famous musician took the trip I was now taking.

It is not always possible actually to land a boat on Staffa, because the sea is quite often too rough for safety, but we were fortunate that day. As we approached the island, the sea calmed enough for us to land and to explore the uninhabited place, graced now by myriad sea birds whose loud cries filled the sky with screeches to challenge the winds and waves. We were, as was Mendelssohn before us in 1829, able to enter the now famous cave, some 60 feet high and easily 200 feet deep into the island. The crashing sound of the waves was certainly unforgettable. It made such an impression on the 20- year-old composer that he on the spot roughed out the tune that I and my companions had just sung together; we know that to be true because Felix sent a letter home not long after his island visit with the tune written out for his parents and sister to see. The entire piece was premiered in London in 1830.

It is not always possible actually to land a boat on Staffa, because the sea is quite often too rough for safety, but we were fortunate that day. As we approached the island, the sea calmed enough for us to land and to explore the uninhabited place, graced now by myriad sea birds whose loud cries filled the sky with screeches to challenge the winds and waves. We were, as was Mendelssohn before us in 1829, able to enter the now famous cave, some 60 feet high and easily 200 feet deep into the island. The crashing sound of the waves was certainly unforgettable. It made such an impression on the 20- year-old composer that he on the spot roughed out the tune that I and my companions had just sung together; we know that to be true because Felix sent a letter home not long after his island visit with the tune written out for his parents and sister to see. The entire piece was premiered in London in 1830.

After some wonderful minutes in the cave, listening to the deep sound of the sea, crashing against the basalt-lined cavern, we headed back to the ship. We made the return trip in near silence, perhaps awed by what we had all experienced together in that cave. It was for me an amazing experience, one I will always hear and recall when I listen to Mendelssohn’s wonderful evocation of the scene, but even when I am not listening to his music, the sound of the cave will rise unbidden from time to time.

However, I reflected on something quite apart from the cave and the sea and the music that I love so well. I thought back to what had happened in Germany some years before with respect to Felix Mendelssohn. Though he was born a Jew, his parents, primarily under the influence of a fanatical uncle, had had Felix baptized a Christian when he was seven years old. That was in 1816, a time when it was still not easy to be a Jew in German society. In fact, Moses Mendelssohn, Felix’ grandfather, was a famous Jewish scholar and among the very first German Jews to have a book published in German and among the first to enter quite openly the high society of German intellectuals. Still, though Moses’ son became one of Europe’s wealthiest men, and though that man’s son became one of the most famous composers and performers of his time, Judaism was still deeply suspect in Germany in the early 19th century.

However, I reflected on something quite apart from the cave and the sea and the music that I love so well. I thought back to what had happened in Germany some years before with respect to Felix Mendelssohn. Though he was born a Jew, his parents, primarily under the influence of a fanatical uncle, had had Felix baptized a Christian when he was seven years old. That was in 1816, a time when it was still not easy to be a Jew in German society. In fact, Moses Mendelssohn, Felix’ grandfather, was a famous Jewish scholar and among the very first German Jews to have a book published in German and among the first to enter quite openly the high society of German intellectuals. Still, though Moses’ son became one of Europe’s wealthiest men, and though that man’s son became one of the most famous composers and performers of his time, Judaism was still deeply suspect in Germany in the early 19th century.

And when the fanatic anti-Semite, Adolf Hitler, became chancellor of Germany in 1933, among his first acts was to forbid the playing of any music written by Jews in the greater German Reich. His own musical hero, Richard Wagner, had written a scandalous screed called “The Jew in Music” wherein he had derided any music written by Jews as useless and in the main less than real music. One of these he had in mind was Felix Mendelssohn. Statues of him in both Leipzig and Dusseldorf were torn down by the Nazis in the 1930’s as a signal to all that his music was not be considered important and was not to be played again. Even today, performances of his music done in Germany list him as “Mendelssohn-Bartholdy,” the Christian name his uncle especially insisted that he use. It should be noted that the composer himself did not use that Christian name with any regularity during his lifetime.

As I travelled back to Mull with my German companions, I remembered this history. Several years prior to my trip to Staffa, I had sung the role of “Elijah,” Mendelssohn’s famous Victorian oratorio, and had given a series of lectures on the life and work of the composer. And because of my interest in mid-twentieth century Germany, I knew well what had happened to the composer during the Nazi period. Somehow, I felt deeply gratified that I had shared a ship to Staffa with a group of German tourists with whom I had witnessed a natural wonder and with whom I had sung the music of one of their compatriots who had been a wonder of his own, had been calumniated by a horde of dangerous monsters, but who had now become once again the German genius that his life and work had demonstrated that he was. I felt that justice had been served for Felix Mendelssohn, and I was again convinced that justice and equality were the way of the universe and that there was indeed a God of justice.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)