The afterlife of the 8-chapter “Song of Songs” is filled with rich and often hilarious ironies. We have no real clues concerning the time and place of its composition, but we surely can know a good bit about what various commentators have tried to make of it. Rather than perusing the long history of the readings of the poem, let me begin with the most recent employment of the book.

The afterlife of the 8-chapter “Song of Songs” is filled with rich and often hilarious ironies. We have no real clues concerning the time and place of its composition, but we surely can know a good bit about what various commentators have tried to make of it. Rather than perusing the long history of the readings of the poem, let me begin with the most recent employment of the book.

Usually in the lectionary we get the song’s chapter 8:6-7, that quite memorable paean to the power of love: “Set me as a seal upon your heart, as a seal upon your arm, for love is as strong as death, passion as fierce as the grave. Its flashes are flashes of fire, a raging flame. Many waters cannot quench love, neither can floods drown it.” Never do the lectionary collectors give us any of the richly sensuous poems from chapters 5 and 7, apparently a residue of the prudishness of the church when it comes to matters of sexuality. Instead, we are to reflect on the general character of love as it is viewed in light of the love of God, or, for us Christians, in the light of God’s love in Jesus Christ. And that leads us to the more ancient readings of the song.

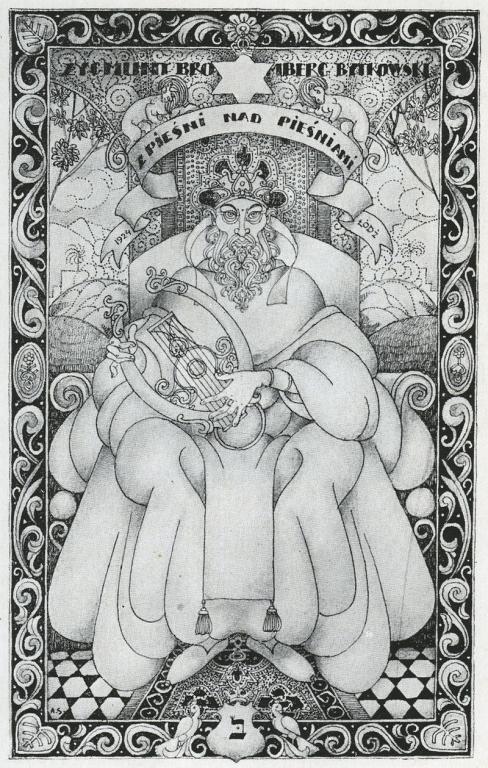

But first, perhaps, a word about the title of the book. It is not in any genuine rendering “The Song of Solomon,” though that is the title one finds in many translations. It is true that Solomon is mentioned in the poem, twice in chapter 3, but there is no real connection to that ancient king in the rest of the piece. In fact, the Hebrew title is most readily “Song of Songs,” but the grammar may also be heard as one of the ways that the language suggests a superlative; hence “Most Beautiful Song” would be an appropriate reading. Whoever wrote the poem, or the series of poems, clearly thought of his/her production as a profound and illuminative testament to the wonders of sexual love. Early rabbinic commentators were not blind to this fact, and wrote of the quite explicit and unmistakable references to the acts of sexual concourse that are described in the poems.

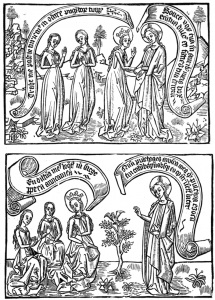

Despite that earliest interpretation, it did not take long for readers, both Jewish and Christian, but mostly Christian, to determine that these biblical poems simply could be what they most obviously were, namely delightful poems honoring sexual romance. All too soon, comments were written that affirmed that the song was “really” about God’s relationship with Israel, or, for Christian readers, Jesus Christ’s love for the true believers. Such views ruled nearly all readings of the poems for centuries.

This narrow lens, probably created by the increasing denigration of sexuality as a barrier to genuine faith in God—why else develop the institutions of the monastery and the convent and a celibate clergy?— brought forth “interpretations” of the poems that can only now be seen as vastly humorous. For example, a reading of 7:2-3, where the female beloved’s navel in likened to a “rounded bowl” and her two breasts to “two fawns” (the same comparison is found at 4:5), suggested to a more prudish reader that the navel was in reality the church’s baptismal bowl and the two breasts referred to the two covenants of law and gospel! Allegory of course allowed and even forced readers to discover the hidden truths of the scriptures; plainly the overt sexuality could not have been what the inspired writer had in mind!

But that is exactly what the writer did have in mind, a wonderful announcement of the power and beauty of sexual love. One hardly need be a subtle literary reader to discern what this poet had in mind when she wrote, “My beloved thrust his hand into the opening, and my inmost being yearned for him” (Song 5:4). Or it does not take any imagination to picture the sensual pleasures of Song 7:7-9: “Your stature is as a palm tree, your breasts like its clusters. I say I will climb the palm tree and lay hold of its branches. O may your breasts be like clusters of the vine, and the scent of your breath like apples, and your sleeping lips like the best wine, that slips down my lover, gliding over lips and teeth.” It is surely difficult to discover in any ancient poetry a riper description of the intricacies and delights of the act of sex. Here is the physical actions of two attracted bodies at its finest!

But why, exactly? What is this book doing in our collection of sacred scripture? I find the answer to that question quite direct and obvious. The acts of sex were and are an enormous part of human lives. Why should we not expect a sacred book that hallows and enshrines those actions as an expected part of what it means to be fully human? Even the denial of sexual congress, enforced on Roman catholic priests by church hierarchy for nearly two millennia, announces as clearly as anything can that sexual activity is central to the human animal; to deny it is a true charism, made possible only by an act of full devotion to God. Little wonder that the church has long been riven by those priests who have clearly not been able to overcome the sexual needs of their humanity, and as a result have abused and destroyed thousands of victims, both male and female, throughout the centuries. Just this past week, over 300 Roman priests were accused of such behavior in Pennsylvania over the past four decades, aided by a hierarchy that, rather than confront the abuse, merely moved the offending priests to other parishes, hoping no one would notice.

I am not a Roman Catholic, so I cannot tell my brothers and sisters of that particular faith what they ought to do to stop such horrors from arising again and again from their ranks. But, I can say this much at least: sexuality is one of God’s great gifts, a delightful and pleasurable benefaction from the God who made us for one another. And as such, sexuality is not easily harnessed, nor is it readily denied.

There is another curious fact about the most beautiful song: God is not mentioned a single time. It may well be that the author was writing a celebration of sex for its own sake, a poem ringing the changes on a series of acts that all knew well, and enjoyed to the full. Still, the fact that the poems ended up in our Bible now provides a richly religious context for the joys of sexuality. It has been said that on Friday nights after Jewish services were completed some centuries ago, it was a divine duty that a couple go home and make love. After all, the act of lovemaking was as close to God as human beings were likely to get. I think the author of the most beautiful song knew that well.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)