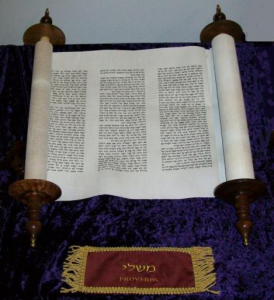

As we near the end of the long summer season, or in churchy terms the season of Pentecost, of Common Time or Ordinary Time, depending on your denominational choice, the lectionary collectors offer for our delectation a very brief look at Proverbs. Beyond the mysterious depiction of the Lady Wisdom in the beginning or the memorable portrait of the “perfect wife” at the end, the Book of Proverbs has rarely served as meat (or vegetables for you so inclined) for preaching. Seldom have the long sections of individual proverbs, perhaps from chapters 10 on, served many preachers as preaching texts. Of course there is that frankly terrifying and terribly dangerous “Spare the rod, spoil the child” (Prov 23:13, among others) that everyone seems to quote, suggesting to some that corporal punishment can be good for children, thus freeing them to beat their offspring when the mood strikes, imagining that they are thereby being faithful parents.

As we near the end of the long summer season, or in churchy terms the season of Pentecost, of Common Time or Ordinary Time, depending on your denominational choice, the lectionary collectors offer for our delectation a very brief look at Proverbs. Beyond the mysterious depiction of the Lady Wisdom in the beginning or the memorable portrait of the “perfect wife” at the end, the Book of Proverbs has rarely served as meat (or vegetables for you so inclined) for preaching. Seldom have the long sections of individual proverbs, perhaps from chapters 10 on, served many preachers as preaching texts. Of course there is that frankly terrifying and terribly dangerous “Spare the rod, spoil the child” (Prov 23:13, among others) that everyone seems to quote, suggesting to some that corporal punishment can be good for children, thus freeing them to beat their offspring when the mood strikes, imagining that they are thereby being faithful parents.

Still, that proverbial injunction makes the point I wish to make today about this long collection of comments and commands in proverbial form: they are not, repeat not, intended as universal truth. They are instead snippets of experience freeze-dried into snappy and memorable statements, designed to engender discussion, leading sometimes to assent and often to dissent. Is it in fact always the case that if you discipline your children with harsh measures, with belts and sticks and the like, that they will automatically avoid the horrors of spoliation, that they will immediately become docile followers of your dictates? Hardly! Our prisons are chock full of men-children who were roundly beaten by their minders as they grew up, and rather than become model citizens, became instead traffickers in violence themselves. To quote any proverb, biblical or not, and assume that you have spoken a truth for all time and places is to speak with little thought.

Let us take some more modern examples. “A rolling stone gathers no moss” is a familiar adage, apparently espousing the wandering life. The proverb seems to mean that if I move around a good deal, I will never stay long enough in one place to “gather moss,” that is to become staid, predictable, fixed in my ways. No, the saying claims, the wandering life is the best life. Well, is it? Sometimes, perhaps, but anyone looking for stability and certainty, for a life partner with whom to settle and love and to grow old together, will find the advice of this proverb well-nigh useless and dangerous, a half-truth at best, a thoroughly misleading suggestion at worst.

“A stitch in time saves nine” is another old adage. This proverb claims that quick action now will save a later need to repair what could have been completed more simply earlier. If I had fixed that tire when I saw it needed fixing, I would not have needed to replace the tire later after it blew out in the middle of nowhere, causing no end of trouble and expense. Surely, here is universal advice that can be very valuable in every situation. Is that so? What if I act too precipitously, thinking I am solving a problem, nipping it in the bud, as another saying goes, but in fact not thinking the problem through well enough actually to deal with the problem completely, and instead of saving time, rather making more work for myself? If I just fire this one employee, surely my team will be more efficient, since my initial perception is that that person is the real problem for our company. But after she is gone, I see that my problem has not been solved, but rather has been compounded, and now I have a deeper issue, one that was there all along, that needs even more of my attention: the “stitch” I first took, did not save me “nine” but added more stitches than I now can count.

Let us now see how this applies to a biblical proverb. “Rich and poor are alike in that YHWH makes all of them,” reads 22:2. Just how are we to hear that? The positive reading might be that all people are creatures of the one God, and as such, a rich person is not intrinsically better than a poor one. Of course, by reading like that I have obviously added an evaluative idea to the saying that is in fact obviously not immediately present in the saying. Because that is so, I could read more negatively that the rich are rich and the poor are poor, because God has made them so; if you are poor, it is because you are destined to be so by YHWH. And if I extend that reading a bit further, I can conclude that poverty is a sign of God’s disfavor somehow, and if a poor person wishes to become rich, it is either impossible, or she might be able to do so by the right sort of prayer or the right kind of worship or the right size of monetary gift to the right sort of preacher. Hence, a television evangelist has another potential victim to bilk. In that way, what appears to be a simple straightforward religious claim can become a monstrously distorted and abusive idea of the ordering of God’s universe.

Let us now see how this applies to a biblical proverb. “Rich and poor are alike in that YHWH makes all of them,” reads 22:2. Just how are we to hear that? The positive reading might be that all people are creatures of the one God, and as such, a rich person is not intrinsically better than a poor one. Of course, by reading like that I have obviously added an evaluative idea to the saying that is in fact obviously not immediately present in the saying. Because that is so, I could read more negatively that the rich are rich and the poor are poor, because God has made them so; if you are poor, it is because you are destined to be so by YHWH. And if I extend that reading a bit further, I can conclude that poverty is a sign of God’s disfavor somehow, and if a poor person wishes to become rich, it is either impossible, or she might be able to do so by the right sort of prayer or the right kind of worship or the right size of monetary gift to the right sort of preacher. Hence, a television evangelist has another potential victim to bilk. In that way, what appears to be a simple straightforward religious claim can become a monstrously distorted and abusive idea of the ordering of God’s universe.

How about 22:8? “Whoever sows wickedness reaps evil; their angry rod will fail.” Really? All the time? The sentiment of the first line serves as the leitmotif for the entire book of Job. It is the litany of Job’s appalling friends; Job must be evil because only evil people end up on life’s ash heaps. But we are told clearly in the book’s prologue that Job is not at all evil, and that he is on the heap because of some sort of wager between YHWH and the Satan, the prosecuting attorney of YHWH’s court. Job’s author will say in as many ways as he can conjure that over and over “those who sow wickedness” by no means always reap evil. In fact, it is rarely the case that that happens in a complex and mysterious universe. Furthermore, “an angry rod” is all too often quite successful in forcing others to bend to the will and whim of the powerful wielder of that rod. As I suggested above, these proverbs are not asking for quick assent, but rather tease our theological minds into active thought.

I would say that the Proverbs are delightful and scary at the same time; they suggest ideas that can be on the one hand life-giving and on the other potentially death- dealing. I contend that their role is precisely what another purveyor of troubling proverbs claimed: “The sayings of the wise are like goads, and like nails firmly fixed” (Eccl. 12:11). To read the proverbs rightly is not to laminate them on placards to be gazed at occasionally, but rather to allow them to become goads and nails, irritants that get under the skin and must be attended to, lest the irritation turn to anger and rejection. Proverbs can make us think, and what can be more valuable than that for a religious community that too often checks its brain at the church door?

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)