Today we will address the first of four weeks on the book of Job. I have revealed in my past blogs on the lectionary my long acquaintance with the book of Job. I wrote a long, and I fear essentially unreadable, dissertation on the book in 1974, being convinced in a typically arrogant graduate student way that I had at last solved the mysteries of the book. In a word, I hadn’t. Then in 1999 I published a book, Preaching Job, in which I attempted to provide both a brief commentary on the whole book of Job and to offer reasons and ways why and how a preacher should pay careful attention to it. And I have continued to share my ever-changing thoughts about the book in various conference and church settings over the years. I say ever changing because Job is the kind of book that never stands still; it keeps revealing new things about itself as one reads it again and again. Perhaps better said, a reader keeps changing as she reads the thing, her angle of vision shifting, her reading lens forever narrowing and widening to encompass new thoughts and ideas. Job is rather like a Rorschach test, evaluating its reader as much as he or she evaluates it. I absolutely delight in the book of Job, and I wish today to tell you why I think the church and the synagogue have misused its treasures and have thereby missed some very valuable insights that the book continues to provide.

Today we will address the first of four weeks on the book of Job. I have revealed in my past blogs on the lectionary my long acquaintance with the book of Job. I wrote a long, and I fear essentially unreadable, dissertation on the book in 1974, being convinced in a typically arrogant graduate student way that I had at last solved the mysteries of the book. In a word, I hadn’t. Then in 1999 I published a book, Preaching Job, in which I attempted to provide both a brief commentary on the whole book of Job and to offer reasons and ways why and how a preacher should pay careful attention to it. And I have continued to share my ever-changing thoughts about the book in various conference and church settings over the years. I say ever changing because Job is the kind of book that never stands still; it keeps revealing new things about itself as one reads it again and again. Perhaps better said, a reader keeps changing as she reads the thing, her angle of vision shifting, her reading lens forever narrowing and widening to encompass new thoughts and ideas. Job is rather like a Rorschach test, evaluating its reader as much as he or she evaluates it. I absolutely delight in the book of Job, and I wish today to tell you why I think the church and the synagogue have misused its treasures and have thereby missed some very valuable insights that the book continues to provide.

But first a brief look at today’s lection. Basically, the lectionary collectors have given for our perusal the prologue of the book, Job 1-2. It is crucial for the whole tale to take this prose prologue with great seriousness, but just as crucial not to over read what is going on here. The first important fact is found in vs.1. “A man there was in the land of Uz; Job was his name. That man was absolutely righteous; he was in awe of God and turned away from evil.” Job, we are told immediately, was a paragon of religious piety. Job has done everything exactly correctly, and is recognized by all his community as the wonderful man that he is. It is essential that as we read the subsequent story that comprises the 42 chapters of the book that we never forget that clear and amazing fact. We should note that this exemplary description of the hero is later found verbatim in the mouth of YHWH at 1:8, a divine proof that Job is who the story says he is.

The second important fact in the prologue is that YHWH does not have a dialogue with Satan, despite the NRSV’s continual use of the name in their transaltion. Somewhat incongruously, the NRSV editors tell the reader this but only in a peculiar footnote: “or the Accuser,” they say, capitalizing the translation of the word for unknown reasons, and then adding “Heb ha-satan.” Such a note is only valuable for those who actually read Hebrew. What they are trying to say is that the proper translation of the word used is “the satan,” satan being a title of some sort rather than a proper name. Here we do not have the devil or Mephistopheles, but a distinct member of YHWH’s court of gods, whose role it is to observe human behavior on the earth and then report to YHWH what he has seen. Now a crucial point: if you blame the subsequent tragedies that befall Job squarely on ha- satan, the entire claim of the book is undercut. The central point of the prologue is to establish that what happens to Job has nothing whatever to do with anything he has done. Quite the contrary! His descent to the ash heap of Uz is the result of some sort of odd and dangerous wager between YHWH and YHWH’s servant, ha-satan, that brings Job to ruin. Fingers are not meant to be pointed easily at either YHWH or ha-satan, though to be sure God will come in for a lot of deep probing. The author is asking the question; what sort of universe do we live in where superbly pious and righteous people end up with nothing? And behind that question is the question of the book: just what sort of God is it that we worship? In the end the book of Job is not primarily about innocent suffering, though such suffering surely occurs. It is about God, pure and not so simple. Who is God after all?

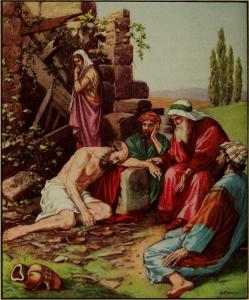

The third basic fact about the prologue is the nature of Job’s friends. Though this section is not included in the lectionary for today, it is important to examine 2:11-13, because it has valuable insights that will tell on the future of the tale. It has often been said that when Job’s three friends show up, supposedly to “console and comfort him,” they are offering to their friend some sort of genuine concern and empathy. I used to think this myself, saying that this scene represents their finest hour, since later in the book they are hell-bent on destroying Job as the monster they suppose him to be in increasingly stinging words. I no longer think that about them in the prologue, because of what they do at 2:12. Oh, they tear their robes all right in apparently appropriate Middle- Eastern mourning, but the strange thing they do next arouses my deepest suspicions. “They threw dust into the air, it falling on their heads.” This peculiar act is found in one other place in the Hebrew Bible. In the sixth plague of Egypt, Moses is commanded by YHWH to “take ash from the kiln and throw it up in the air; it shall become fine dust all over the land of Egypt, and shall cause festering boils on humans and animals;” (Ex.9:8- 9). I think there may be great humor here. By tossing the dust up in the air, the friends imagine that they might cause boils to break out on Job; instead the dust falls on their own heads! And precisely nothing at all happens.

The fact is that the very sight of Job sitting alone on an ash heap, clothed in a filthy rag, scraping himself with a broken piece of pottery, is proof enough for them that he is nothing less than the foulest sinner in the world. In their theology, described at nauseous length in the dialogues to come, only sinners end up on ash heaps. There is no empathy here at all, merely the desire to witness the suffering and certain death of an obvious sinner and perhaps with their dust conjuring trick a hope to speed him off to Sheol more quickly. And the friends expect just that, namely Job’s death in silence and pain. Of course, that is precisely what they do not get! And with those three facts, we are ready to read the dialogue to come.

I suggested above that I wanted to point to ways that the church has missed the true value of the book of Job. I plan to fill out this notion in multiple ways in the next few essays. For today, let me say that the trivialization of Job has been a feature of the church’s abuse of the book. He represents “patience,” though if he does it lasts merely two chapters of 42! He is the “pious sufferer rewarded,” but if he is the book is a kind of dark joke, wherein Job is assaulted in terrible ways only to be rewarded for his stoic refusal to curse God, thereby modeling for us a life of pain leading to inevitable joy and success, a sort of prosperity gospel of the ancient world. Job’s reward, if it be such, has nothing whatever to do with what he has done or not done, as we will see. Besides, I would suggest that he does curse God roundly and continually; if 9:22-24 is not curse I do not know what it is!

What the church has lost in its misuse of Job is the honesty, the unwillingness on the part of Job to “go gently into that good night.” He rages and rages at the dying of the light, not giving in to simple and common bromides of the faith, but demanding loudly that the world appears to make little lasting sense and should cough up its truths to those who need them by which to live. YHWH coughs up some truths all right, but the content of those truths is the final subject of the book, and will bring to us the book’s real and lasting importance. Job is a thrilling book, and well worth a lifetime of reflection. Next week, I will offer more by way of such reflection, proving, I hope, that Job needs to be more at the center of the Bible’s gifts rather than only on its dim periphery.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)