With this second week on the book of Job, the lectionary connectors offer us a rather peculiar text. It is Job’s response to the third speech of Eliphaz (Chapter 22), and frankly is the final clear speech in the much disputed third cycle of speeches. Job 24-27 is a hodge-podge of pseudo speeches, seemingly ascribed to the wrong speakers, the friends sounding rather like Job (25) and Job sounding rather like the friends (26). Oceans of scholarly ink has been spilled attempting to untangle the mess that constitutes the third cycle, but no agreement on how to make it clear is likely to happen. However, I think it is fair to conclude that Job 23 is a Joban speech.

With this second week on the book of Job, the lectionary connectors offer us a rather peculiar text. It is Job’s response to the third speech of Eliphaz (Chapter 22), and frankly is the final clear speech in the much disputed third cycle of speeches. Job 24-27 is a hodge-podge of pseudo speeches, seemingly ascribed to the wrong speakers, the friends sounding rather like Job (25) and Job sounding rather like the friends (26). Oceans of scholarly ink has been spilled attempting to untangle the mess that constitutes the third cycle, but no agreement on how to make it clear is likely to happen. However, I think it is fair to conclude that Job 23 is a Joban speech.

It follows a recognizable pattern from earlier speeches from Job. Vss.2-7 present a wishful hope that Job might finally confront God directly in God’s “dwelling” (23:3). In that meeting Job would “lay his case before God, and fill his mouth with arguments.” Also, Job would at last “learn the words with which God would answer and perceive what God is saying” (23:5). This expectation summarizes Job’s terrible dilemma that has formed throughout the story. Job has been reduced to penury and pain on the ash heap of Uz and does not understand how this could have happened. He is a deeply pious and uprightly righteous man who expected, given his received belief, that good behavior receives good things from God. In this Job and his friends have a similar belief in a God who rewards good and punishes evil. Where Job and the friends diverge, of course, is the idea of Job’s supposed righteousness. They believe him to be evil since their own eyes witness him as receiving the inevitable reward of that evil. But Job, to the contrary, is convinced he has done nothing at all worthy of his now appalling life, and because he and the friends also are certain that God is responsible for everything in the universe, Job has concluded that his enemy is none other than God. Indeed, in the first two cycles of speeches Job assaults God without mercy, giving the lie to those who claim, quite foolishly, that “Job never blasphemes against God,” and at the same time bringing the ultra pious friends to an apoplectic state.

For example, after Job unleashes a shocking attack on the Deity at 9:22-24, accusing God of destroying both righteous and wicked indiscriminately, and laughing as they all die (!), Zophar is moved to say, “God exacts of you less than your guilt deserves” (11:6; is God about to grab Job’s broken pottery piece, too?) and “a stupid person (Job) will gain understanding on the same day that a wild ass is born human” (11:12) a very clever jibe but darkly twisted and cruel. This makes it quite plain that the friends have abandoned all pretense of helping Job, if they ever had any such intention, and have now turned to overt animosity and desire for his destruction. And so the argument is joined. Job claims he is innocent and must assume that God is attacking him for reasons he cannot begin to comprehend, while the friends claim that Job is evil and is getting from God what he so richly deserves.

But in the face of this terrible conundrum—Job is under attack by God, but since God does all Job can only appeal to that same God for redress—Job again and again attempts to contact God, continues to try to coerce God into talking to him, answering him, giving him reasons for God’s apparent hatred of him. Job 23:2-7 offers still another such appeal. If only they could talk! In what appears to be a vain wish, Job says, “Would God go to court with me with mighty power? No! That God would actually pay attention to me! There (in God’s dwelling) an upright person could reason with God, and I would be found innocent forever by my judge” (23:6-7). This plea reminds us of the prologue where twice Job was called “upright,” using this same Hebrew noun. Earlier in both chapters 9 and 12, Job has feared the worst in a meeting with God, primarily because God’s power is always on display, leading Job to believe that God would pay no attention to puny Job. But he always retains that slim hope that God might actually listen to him and he repeats that hope here in chapter 23.

But 23:8 pushes Job back into despair. The main reason is that he just cannot find God! “Look! Forward, but God is not there; backward, but I cannot see God. On the left, God hides and I cannot envision God; I turn right but see nothing” (23:8-9). But now again, a burst of hope: “God knows the way I take; when I am tested I shall come forth as gold” (23:10)! 23:11-12 add to his rising hopes, as Job shouts again that “my foot has held fast to God’s steps; …I have never departed from the commandments of God’s lips.” Surely, when God finally sees these facts with clarity, God will take away God’s curse and Job shall be what he once was, a man of power and honor in the community and one loved by God.

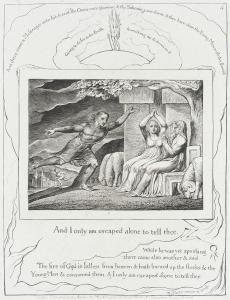

But a dark speculative reality again clouds Job’s mind as he returns to despair. “But God stands alone; who can turn God around? Whatever God desires, God does! God will finish whatever is determined for me; many similar things are in God’s mind” (23:13-14). As a result, Job “is terrified at God’s presence and when I consider, I am in dread” (23:15)! “God has made my heart weak; Shaddai has terrified me! I wish I could vanish in darkness, and the thickest darkness could cover my face” (23:16-17)! Job’s hopeful meeting with God where he and God could clarify the real meaning and purpose of his life has become a terrifying desire to avoid God altogether, shrouded in darkness and gloom. Job thus returns to his earlier desire to fall into Sheol thus hiding forever from this God who has assaulted him and has no apparent intention of doing anything else (Job 10:18-22).

Job spends the bulk of his tale pinballing back and forth between a kind of steroid-fueled hope and desire to meet God to straighten out between them the obviously confused situation of Job’s attack by God, and the conviction that no meeting with God is possible, or if one ever happened it would be useless since God, wrapped in wonder and power, would pay no attention to Job at all (Job 9:3,16). When God does finally appear, and that appearance is delayed for 15 more chapters, that appearance is a grand surprise for Job, his friends, and for the reader, as we will examine more carefully next week.

I said in my last essay that the church lost something very important when it trivialized this book into a story of a pious man restored, or a patient man rewarded. Ironically, when the church treated the book in such fashion, it precisely avoided and discarded some of the central ideas the book put forward, namely, that God is not easily understood and that those who would wrestle with this God are in for a hard tussle. The book is not about remaining pious for God, or saying nice things about God, defending God from so-called blasphemous and hard questions about God’s nature and purpose. To the contrary! Hard and persistent questions about and to God are the very stuff of piety, the essence of a workable faith. In that, Job is our model, and his continual movement between hope and a despairing anger mirrors many of our honest struggles with faith in this mysterious God. No genuinely faithful person has failed to make this same difficult journey as she/he travels the rocky road of faith. Job is no model of piety for us; he is a model of honesty and perseverance that we have lost in our churches to our great detriment.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)