Those of us who have had the privilege of reading the Bible for the church for many years know all too well that there is in fact no “plain meaning” of the biblical text. As often as those who make that claim, especially those who imagine that anyone can translate “what the words say,” if they are able to read the ancient languages, are quite simply uttering a gigantic falsehood. There is no “plain meaning” of ancient texts, because translating words and phrases from ancient writing to modern culture is a vast leap through time and space that inevitably involves quite specifically the one doing the translation. Who I am as translator—my age, my gender, my education, my political and social inclinations, my literary acumen, along with a host of other factors—profoundly and thoroughly impact how I hear and render the words into a contemporary idiom. The simple fact is: the reading of any text is an act of complexity that is too often misunderstood, and the act of reading ancient texts, especially biblical texts, is no different. The true presence of God is hardly locked into the ancient words. The actions of any translator occur somewhere above the text, between the words and the one reading. God’s Spirit only may appear at that place where text meets reader, a few feet above the text. And only when that reader comes clean about who she/he is may a translation be said to occur, a translation forever tainted and shaped by that particular translator.

Those of us who have had the privilege of reading the Bible for the church for many years know all too well that there is in fact no “plain meaning” of the biblical text. As often as those who make that claim, especially those who imagine that anyone can translate “what the words say,” if they are able to read the ancient languages, are quite simply uttering a gigantic falsehood. There is no “plain meaning” of ancient texts, because translating words and phrases from ancient writing to modern culture is a vast leap through time and space that inevitably involves quite specifically the one doing the translation. Who I am as translator—my age, my gender, my education, my political and social inclinations, my literary acumen, along with a host of other factors—profoundly and thoroughly impact how I hear and render the words into a contemporary idiom. The simple fact is: the reading of any text is an act of complexity that is too often misunderstood, and the act of reading ancient texts, especially biblical texts, is no different. The true presence of God is hardly locked into the ancient words. The actions of any translator occur somewhere above the text, between the words and the one reading. God’s Spirit only may appear at that place where text meets reader, a few feet above the text. And only when that reader comes clean about who she/he is may a translation be said to occur, a translation forever tainted and shaped by that particular translator.

Today’s text offers a classic illustration of the difficulties of the art of translation. The way that one construes 1 Sam.1:5 will determine in part how one is to judge the character of Elkanah, husband of Hannah, mother of Samuel. And around that judgment revolves one’s understanding of one of the central claims of the story: just who is Elkanah and what is his relationship to his wife, Hannah?

The NRSV translates 1 Sam. 1:5 as follows: “but to Hannah he gave a double portion because he loved her, though the LORD had closed her womb.” In this reading Elkanah is an altogether laudatory husband. He has two wives, one of whom, Peninnah, is marvelously fruitful, bearing her husband many children. Hannah, to her shame in this ancient culture where women were prized for their abilities to have babies, is barren. It is obviously not Elkanah’s problem that Hannah can have no children; Peninnah is witness to that fact. And to make matters worse, Peninnah apparently enjoys her birthing prowess so much that she “provokes” and “irritates” her co-wife, making fun of Hannah’s perpetual flat belly while Peninnah swells with pride, and yet another child (1 Sam.1:6).

In response to the rancor between his two wives, according to the NRSV, Elkanah treats Hannah with special deference, offering to her “a double portion” of whatever he gives to Peninnah and her children. In other words, Hannah is given special treatment in an apparent attempt to cheer her up and to suggest that Elkanah, despite her barrenness, loves her still. After years of this behavior from Elkanah and Peninnah, Hannah finally has had enough, weeping and refusing to eat due to her public shame (1 Sam.1:7). Once again, Elkanah seeks a soothing word by saying, “Why are you weeping? Why are you not eating? Why are you sad? Am I not better to you than ten sons (1 Sam.1:8)? We might conclude that Elkanah is doing his best in a bad situation that apparently is no fault of his own. Again, how could anyone fault his behavior?

However, a closer look at 1:5 might suggest a very different evaluation of Elkanah and might in turn suggest that Hannah has more than a problem with Peninnah and her cursed fruitfulness; Elkanah might be a further pain in her attempt to find her way in Israel. To be fair, an NRSV footnote does warn us about its “translation” of 1:5; it offers us the ubiquitous phrase “Meaning of Heb uncertain,” and tells us that the Syriac translation of the Bible has provided the basis for the reading they have given in the body of the text. Let me suggest a possible reading of the Hebrew of 1:5: “To Hannah he gave a single portion before (earlier?), because he loved Hannah and YHWH had closed her womb.” Granted, the word I have translated as “before” or “earlier” is difficult, but it is translated like that in several other passages in the Bible. In 1 Sam 1:4, we are told that Elkanah gave “portions (plural) to Peninnah and her sons and daughters,” implying a bounty of gifts, while in contrast he gives to Hannah merely “a single portion.” He may have loved her, but that love does not cause him to shower Hannah with gifts; instead he offers her only one portion.

If that is a possible meaning of 1:5, then his attempts to console Hannah’s broken spirit at 1:8, telling her that he is in fact “worth more to her than ten sons,” sounds rather more like the pathetic words of a chauvinist, narcissistic pig who fancies himself all that any woman could ever want! Thus, a reader could conclude that Hannah must contend both with a preening, overly fruitful mother and her vast brood of Elkanah’s children, and Elkanah himself who cannot begin to imagine his other wife’s horror and shame at her inability to bear a child, offering to her his loquacious self as substitute. Never once does Elkanah stop to consider more precisely just what Hannah may in reality need from him and from the dark world she encounters each day.

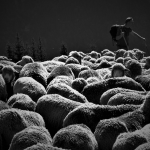

Given that potential understanding of the facets of the story, is it any wonder that when Hannah does give birth, after her desperate pleadings with still another clueless man, the priest Eli, that she now refuses to accompany Elkanah, Peninnah, and their gaggle of kids to the yearly sacrifice in Shiloh? She has her own son now, named by her as Samuel, and has no further need either of her nasty co-wife or her unaware husband. I hope you can see just how different the story is when read as I have suggested.

But why have I read like that? There are many reasons, but all of them have to do with the sort of person I have become in my long 50-year relationship with the Hebrew Bible. I came to the Bible from the background of a serious student of English literature. In fact, I had not read the Bible much at all when I first confronted it, but I had read vast swathes of English prose, from Dickens to Austen to Melville to Hawthorne, among many others. To me, the Bible’s great tales were more of the same, namely stories to be analyzed for plot, character, point-of-view and all the other tools that I had learned in my years of reading. In addition, all that reading had taught me to be critical about what I was reading, never to take that reading at simple face value. I was deeply influenced by that extraordinary American poet, Emily Dickenson, who once said, memorably, “Tell all the truth you can, but tell it slant.” Nearly from the moment I read that, I became what I hope I am: a discerning reader of texts. On occasion, my discernment, my “slantedness,” leads me into the fields of cynicism, or perhaps more accurately said, the darker view of human behaviors. I hear Elkanah as I do, because I know from my reading of Ruth, that book that canonically immediately precedes this story of Hannah, that women have a hard road in the ancient world, but that the Bible often offers to women alternative viewpoints that can provide models that go against the male-dominate world that clearly is the locus of the Hebrew Bible. As a male, I have long found it one of my responsibilities to lift the place of women from a second-class tier up to a measure of genuine equality with those of us males who too often take our status of power for granted. And that personal idea of responsibility of course sharply focuses my reading of this particular text.

To repeat: there are no “plain meanings” of biblical, or any other, texts. Translators are interpreters, and our interpretations are determined by multiple factors of who we are. I hope I have made that reality plain. The goal of any translator is to come clean with all other translators concerning the lenses through which we view those texts we are translating. Until we can do that, we will continue our dance of “you are wrong” and “I am right” when it comes to understanding what the ancient text is trying to say. Down that long road lies division and separation, making a mockery of Jesus’s desire that “all should be one.” I hope to have more to say about this translation dilemma in future essays.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)