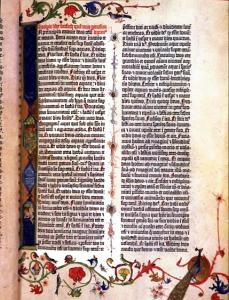

The Bible is a glorious, frustrating, challenging, absurd, delightful book, or a collection of books, or a lengthy, choppy, over-arching narrative, or a hodge-podge of disparate writings, representing nearly 1500 years of human thought. It has been characterized as all of these things, as well as in numerous other ways, by readers over many centuries. Just how one delineates the book will go a long way in determining just how one reads it, as I will discuss in this first look at the most bought, least read book in the history of the world.

The Bible is a glorious, frustrating, challenging, absurd, delightful book, or a collection of books, or a lengthy, choppy, over-arching narrative, or a hodge-podge of disparate writings, representing nearly 1500 years of human thought. It has been characterized as all of these things, as well as in numerous other ways, by readers over many centuries. Just how one delineates the book will go a long way in determining just how one reads it, as I will discuss in this first look at the most bought, least read book in the history of the world.

I have been reading, contemplating, writing about, and orally expounding the Bible for now 50 years. Ever since I almost literally stumbled into a class in introductory Hebrew in 1968, chosen primarily because the stuff looked funny, I have been captured, intellectually and emotionally, by these ancient writings. From Louisiana to Texas to New Mexico to Oklahoma, and in some 40 more US states, and from Okinawa to Germany to England to Brazil, I have carried the Bible and spoken from its pages, both in sermon and in classes of clergy and laypeople. In addition, as a professor of homiletics for almost 30 years, I listened to some 3000 student sermons, twice, each one ostensibly based on this Bible, save the few Unitarian students that dotted my classes along the way. As you can see, the Bible has been the foundation of my professional and personal life. And though that is clearly so, I have spent little time actually reflecting on the specific ways I approach these texts, because I have been far too busy doing what it is I do. This past Sunday I was speaking to a group of highly sophisticated listeners about one of my favorite Bible subjects, the first king of Israel, Saul, and while I was expounding that text, albeit in an unfortunately too brief compass, I was at the same time thinking to myself that I needed to come clean on what I was actually doing. That may sound absurd, and I assure you that I was not speaking out loud two separate subjects, but there was a tiny voice somewhere in my cranium that cried out to be heard—just what is it you are doing, Holbert? Why are you talking about the text exactly like this?

So, I determined that in a series of essays, I would share with you, my few faithful readers, the ways that I approach the Bible for study, for sermon, for teaching. In today’s installment (I have no idea how many installments will finally exist), I propose to address the most basic issue that must be confronted when one opens the Bible to read—just what is it that I am reading? That may seem quite obvious, but believe me, the answer to that question is both crucial and complicated. I know full well, as do each of you, that the Bible is made up of many sorts of literary pieces: poems, stories, laws, aphorisms, riddles, parables, and subgroups of each of those categories. It has long been the simplest of demands that the way one reads depends directly on the type of thing one is reading: you do not read a biology textbook examining its literary stylings; you read it to find out something about biology. It, of course, will be helpful if the author of the textbook writes an understandable if not limpid prose, but she will not be judged or evaluated primarily on that facet of her book, but on her presentation of the ins and outs of biology.

The same dictum applies to the Bible, although unfortunately many readers do not take this very basic demand as seriously as they ought. Allow me to use the example of my class on Saul mentioned above. The books of 1 and 2 Samuel are plainly narrative accounts of the beginnings of the Israelite monarchy and its astonishingly complicated and confusing portrayal. The story is rich with irony, steeped in tragedy, and offers human portraits unmatched in the writings of the ancient world. However, one can only conclude as I have just done when one comes to the text with eyes unclouded by any preconceived ideologies. If one’s religious preconceptions have already determined, for whatever reason, that the text must say certain things about God and about the chosen ones of God, then the text itself will not be allowed to have its full say. Perhaps put another way: the text is not and was never intended to be any kind of propaganda, supporting only one way to read what it says. When read with as much openness as one can muster, the narrative of Samuel, Saul, and David, may be heard as a complex series of portraits that defy simple characterizations. Samuel is not merely a simple and faithful prophet of YHWH, but a human father and leader whose actions are driven by much more than adherence to the word of his God. Saul is far more than a foolish king who disobeys the word of YHWH and is deposed by Samuel and God for that unfaithfulness, as the dunderhead who wrote the Chronicles would have you believe. David is not merely “a man after God’s own heart,” piously writing and singing psalms, directing choirs, and worshipping YHWH the livelong day, but is to be seen as also something like a Mafioso Don, consigning an old helpless enemy to a bloody death on his own deathbed, demanding that his own son, Solomon, perform the deed.

In short, 1 and 2 Samuel are not history in any straightforward sense of that term; you ought not read those texts attempting to glean actual proof of the actions of these men at some particular point in their history. These texts are told, shared, as brilliant pieces of imaginative literature, and need to be addressed as such. Just as I read Dickens or Melville, looking for plot and character painting and the point of view of the actors and action, so I read stories like 1 and 2 Samuel. If I do not, I will shortchange the vast artistry of these extraordinary authors, and will not give my fullest attention to what they have actually composed. And even worse, I will misread them and create from them ideas and formulations that have little to do with what they imagined they were doing. The most egregious example of this misreading may be found in the book of Jonah where far too many readers still hunt for a fish big enough to swallow a man, an ancient city large enough to require a three-day walk, and a historical conversion of Ninevites to match the reluctant evangelistic miracle wrought by the so-called prophet. Jonah is literature, plain and simple, not history in any sense at all. And though it might be said that 1 and 2 Samuel is some kind of history, it is first and foremost literature and must be approached as such.

And so must poems, like the psalms, and so must the parables of Jesus. They are literary artifacts, and the skills of the literary reader must be applied to them. The result? A richer appreciation of the ancient artist and a more appropriate evaluation of the actual writings that we have been given. The effect of such reading is profound and important. I move beyond a thin appropriation of the ancient words toward a recognition that these writers were struggling with what we continue to struggle with, namely, a mysterious God not easily grasped, and complicated human interactions that still challenge and confuse us as we strive for faithfulness to that God. The ancient texts are thus not so ancient after all; they are as modern as our confusing and frustrating lives are today. But what a gift they are to us! The narratives still can speak, and do speak, once they are read and appropriated for what they truly are. Reading the Bible can be both fun and uplifting and immensely challenging for us moderns, making the old book still powerfully current. In future essays I will explore further ways that I use to approach the Bible. Stay tuned!

(images from Wikimedia Commons)