Last week I introduced our six-week look at the enigmatic book of Revelation with a brief glance at chapter 1, especially at its concern with numerology. This sort of writing, commonly called apocalyptic, enjoyed the play of numbers as it expressed important ideas to its readers/hearers. We saw that John the Revelator particularly used the numbers 3 and 7 as he began to unroll his dramatic tale of God as ruler of all things and God’s rejection of the economic and social world of the Roman Empire. These numbers will continue to play significant roles as the story unfolds. But today I want to introduce a second element of much apocalyptic literature, namely the appearance of images, pictorial portraits of animals and persons, both fictional and real, that suggest ideas in wonderfully imaginative forms. Both of these characteristics, numbers and images, will appear again and again in John’s work, and the attentive reader will always need to be on the lookout for both. The most famous of these, the beast of Rev.13, whose number is 666 (or 616 in several Greek manuscripts) we will examine more carefully in a later essay.

Last week I introduced our six-week look at the enigmatic book of Revelation with a brief glance at chapter 1, especially at its concern with numerology. This sort of writing, commonly called apocalyptic, enjoyed the play of numbers as it expressed important ideas to its readers/hearers. We saw that John the Revelator particularly used the numbers 3 and 7 as he began to unroll his dramatic tale of God as ruler of all things and God’s rejection of the economic and social world of the Roman Empire. These numbers will continue to play significant roles as the story unfolds. But today I want to introduce a second element of much apocalyptic literature, namely the appearance of images, pictorial portraits of animals and persons, both fictional and real, that suggest ideas in wonderfully imaginative forms. Both of these characteristics, numbers and images, will appear again and again in John’s work, and the attentive reader will always need to be on the lookout for both. The most famous of these, the beast of Rev.13, whose number is 666 (or 616 in several Greek manuscripts) we will examine more carefully in a later essay.

It should be remembered that this particular literary style that appears to us to be so bizarre, well-nigh impenetrable for some modern readers, was in fact quite common in late Judaism and early Christianity. Many books that reflected apocalyptic influence were produced in the years surrounding the end of ancient Judaism and the rise of the Christian movement. Certainly, the very nature of the style, with its use of number codes and strange beasts was designed to have a short shelf life. It did not take many years to make both numbers and images difficult to understand, given the changing times and mores. Since historical study of the Bible is a quite recent phenomenon, beasts and seals and trumpets could easily be uprooted from their original historical moorings, and would thus lose their meanings as the contexts of the readers moved further forward in time. This is the very reason that modern day mountebanks attempt to make these sorts of texts mean all manner of absurd things, connecting them to all kinds of end-time scenarios, filling football stadiums with eager believers hoping to gain certainty concerning what God is about to do with the world. There is much loot to be gained by these efforts; witness the jets that fly these so-called preachers all over to propagate their nonsense.

Let us be clear; the book of Revelation is not some book of occult prediction, and God has not herein laid down the step-by-step future of the earth. Revelation is, as all other biblical books, the product of a certain time and place, and only a careful reconstruction of that time will offer to us crucial insight into its meaning then and therefore its possible meaning and value now. As I said last week, I believe that John’s Revelation was composed toward the end of the first century CE, during the reign of the emperor Domitian, an especially unsavory leader of Rome, despised by most of the Senate and loathed by early Christians as a blasphemer who claimed to be some sort of divinity, demanding worship. His murder in 96CE was no doubt welcomed by many, both Roman and non-Roman.

How then does John describe for us just how Jesus, the crucified and risen one, gained final victory over the Romans? That is after all the central reason for John’s composition: the Romans who claim to control the world through their laws, roads and legions, according to John in fact do not control anything, since God controls all. Rev.5 is a parade example of how John goes about his amazing work. It is of course important to remember that by all reality, John is completely wrong in what he claims and is dangerously naïve to imagine that Rome is not master of all things. In every city of the empire, Roman might is displayed in vast and impressive buildings, in the presence of Roman legionnaires, in the existence of Roman coinage and taxes. To say that Rome is not the world’s only power is to flaunt the truth of one’s senses and to risk censure, punishment, even death. As I noted last week, John himself was apparently in the Roman prison of Patmos, “on account of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus,” serving a sentence for preaching what Rome plainly did not wish to hear. We have no way of knowing just what the content of John’s preaching was beyond its obvious offense to Rome, but it surely consisted of such language that made the Roman authorities uncomfortable enough to cause them to send John to Patmos.

I doubt that John preached as he wrote, since if he did he could risk being thoroughly misunderstood by those not attuned to the special apocalyptic style. Above all, John apparently wished that his Roman hearers were crystal clear that he had no desire to follow the dictates of the Romans, since he had discovered a new master, the only real master, in Jesus Christ. And in Rev.5 he provides for them and for us one of his most striking creations, an unforgettable image that once heard is fixed in our minds forever.

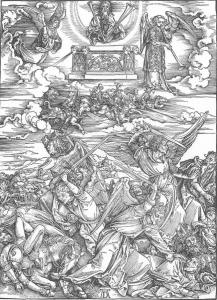

At the beginning of Rev.5, John is in the midst of a dream-like sequence where he is wafted up into the heavenly realms and witnesses the actual court of God. He sees there a great throne, sitting on a sea of glass, rather like crystal, he says (Rev.4:6). Surrounding the central throne John sees 24 thrones encircling the one central throne, and seated on the thrones are 24 elders each with a golden crown. From the central throne John sees flashes of lightening and peals of thunder, accompanied by seven torches, which, he says, are the seven spirits of God. After further weird descriptions of four living creatures, one like a lion, one like an ox, one with a human face, and one like an eagle, all flying about with six wings and screaming continuously “Holy, Holy, Holy, the Lord God Almighty” (see Is.6 for similar creatures and words), John then spies in the right hand of the one seated on the central throne a scroll. Suddenly, a “mighty angel” demands, “Who is worthy to open the scroll and to break its seals” (Rev.5:2)? But unfortunately, “no one in heaven or on earth or under the earth” was found worthy to open the scroll and to read it. As a result, John “wept much” that there was no worthy one. It is clear that someone must open this divine scroll, but only a worthy one can do so.

Then one of the elders turns to John and says, “Do not weep! The lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that he can open the scroll and its seven seals” (Rev.5:5). Ah, thinks John, of course! The conquering hero, the heir of David, the ultimate man of power, he will he able to open the scroll, which apparently is the scroll that will reveal the desires of God for God’s people. Only those who have conquered,  who have defeated strong enemies, can be fully worthy to reveal the destiny of the world. That is the Roman way!

who have defeated strong enemies, can be fully worthy to reveal the destiny of the world. That is the Roman way!

But now John springs his great surprise! He looks all around the scene, attempting to discover the man of power who will by dint of his might be able to open the scroll, peering “between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders” (Rev.5:6). But instead of the Lion of the Tribe of Judah, John sees “a Lamb standing as if it had been slaughtered; the lamb had seven horns and seven eyes which are the spirits of God.” It is this lamb, the slain lamb, who saunters over to the throne and takes the scroll from the right hand of the seated one. Immediately, the four living creatures and the 24 elders fall down before the lamb, each now having a harp and a bowl of incense, “which are the prayers of the saints,” and they begin to sing a new song: “You are worthy to take the scroll and to open its seals, for you were slaughtered and by your blood you ransomed saints from every tribe and people and nation and language; you have made them to be a kingdom of priests serving our God” (Rev.5:9-10).

It is not the being of power that is worthy to reveal the destiny of the world; it is the slain lamb, the martyred Jesus, the one who gave himself for all who is found worthy. In other words, the Pax Romana, a so-called peace created by the power of the sword, is no peace at all and is not the destiny of the world. Only the one who gives himself for all, who is willing to die for the good of all, can be the model for our lives. Here is power in weakness; here is success through giving. No lion finally is worthy to serve as model, but only the slain lamb. In this astonishingly memorable image does John announce to the Romans of his time and to all those persons of power of every time who think they can control the world through might and force, that they are doomed to ultimate failure. True success only comes through the gift of one’s life for others. In this beautiful image John well summarizes the gospel message for his time and all time. In this way, the book of Revelation becomes the full unveiling of the gospel of peace through service and suffering. It is hardly the scary book that so many have found it to be!

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)