By my own rough count, I have written for Patheos seven essays on a biblical text for the Day of Pentecost. I have not gone back to read those articles—there is something about reading one’s earlier work that causes bad cases of hives—but I can bet that many of them focused on the Genesis tale of the Tower of Babel; I do, after all, look first and most longingly at the Hebrew Bible offer of the day. This year on this so-called “birthday of the church” Sunday I will surely glance at Genesis as the origin story of Acts 2’s Petrine sermon, but my interests are focused this time on that verse that states “How is it that we hear, each one of us, in our own native language” (Acts 2:8)? I want to suggest to you preachers and teachers that here is the basic goal of all of your churchly work: to enable your hearers genuinely to hear the word of God in their own native language.

By my own rough count, I have written for Patheos seven essays on a biblical text for the Day of Pentecost. I have not gone back to read those articles—there is something about reading one’s earlier work that causes bad cases of hives—but I can bet that many of them focused on the Genesis tale of the Tower of Babel; I do, after all, look first and most longingly at the Hebrew Bible offer of the day. This year on this so-called “birthday of the church” Sunday I will surely glance at Genesis as the origin story of Acts 2’s Petrine sermon, but my interests are focused this time on that verse that states “How is it that we hear, each one of us, in our own native language” (Acts 2:8)? I want to suggest to you preachers and teachers that here is the basic goal of all of your churchly work: to enable your hearers genuinely to hear the word of God in their own native language.

Perhaps an important caveat first. Acts 2 has nothing whatever to do with that first-century phenomenon known as glossolalia, or “speaking in tongues”. There are no doubt other places in the New Testament where this religious activity is described, most especially by the apostle Paul. In his first letter to the young church at Corinth, Paul recognizes and names “tongues speaking” as a gift of the Spirit, but he quickly adds that without an interpreter of these angelic, hence ununderstandable, utterances, the act has meaning only for the one speaking, and does not build up the church (1 Cor.14:4). He urges all in his fellowship rather to strive for prophecy, that is preaching. After all, says Paul, “If I come to you speaking in tongues (which Paul admits is one of his spiritual gifts), how will I benefit you unless I speak to you in some revelation or knowledge or prophecy or teaching” (1 Cor.14:6)? In other words, tongues speaking may be spectacular, it may mark the speaker as somehow uniquely connected to the power of the Spirit, but it does the community no immediate good at all. Now that you know that, it is doubly important to conclude that Acts 2 is not about that experience, but is rather about something else entirely.

I have long believed that Luke’s Book of Acts contains only tiny bits of actual history. The book instead is a theological-literary exploration of the origin and rise of the early church, building on Luke’s volume one gospel of Jesus. There is, for example, little historical proof that Paul ever actually was in Athens, despite what Acts 17 claims for him there. More to the point, Luke’s glorious portrayal of Peter as ready to jettison his Judaism after a dramatic vision of a heavenly sheet crammed with unclean animals, flies right in the face of the portrait of Peter that Paul gives us in his early letter to the Galatian Christians where Paul says he had to rebuke Peter for his hypocritical attempts to force Jewish practices on would-be converts, while at the same time eating with Gentiles. This does not sound like a willing and public participant in the Gentile mission that Paul so eagerly embraces. There are numerous other places in Acts that call its historicity into serious question.

I would suggest that Acts 2 is no more historical than Paul’s supposed trip to Athens. It is instead a picture of the idealized origins of the church, characterized by a rip-roaring sermon from Peter—that same Peter who had denied Jesus three times and who ran away in horror and fear, leaving only women at the tomb of the Master—a hoard of weeping converts, and a crowd of astonished folk who are hearing the whole address in their own languages, though the speaker is only a Galilean fisherman. Here we find a miracle, nothing less, where Peter becomes the greatest Christian preacher ever, a true lion of the word of God. “All hear in their own languages, Parthians, Medes, Elamites, Mesopotamians, Judeans, Cappadocians,” among others. A quick glance at the nations and tongues mentioned here would suggest that the entire known world is represented, most particularly by Rome in vs.10. Rome was the world’s center in the first century, and Luke wants all to know that when the church was birthed, Romans were there. At the very end of Luke’s treatise Paul will be in Rome, the center and end of the earth, preaching openly the gospel of Jesus. History tells us that Paul died there, perhaps in a Roman prison, but Luke claims that Paul is preaching freely, just as Peter did at Pentecost. In that way the story comes full circle.

And the Day of Pentecost comes full circle in another larger context. The well- known tale of the Tower of Babel, and its concern with the birth of the world’s languages, are the clear contexts of the tale at Pentecost in Acts. The languages appear at Babel’s tower as a punishment from YHWH against the tower builders, who, instead of “multiplying and spreading abroad,” as YHWH had demanded, decided to stay in one spot and build their tower as a direct assault against the power of YHWH. Of course, their supposed massive tower, “with its top in the sky,” cannot even be seen by YHWH who must “come down” to have a look! Not only have they attempted a kind of assault against the rule of YHWH, they have also quite foolishly determined to build their sky tower out of “mud brick and pitch.” Every Israelite knows all too well that one cannot build an outhouse out of mud brick and pitch! All buildings must be made of stone, of which Israel has a surplus everywhere. So to prevent the fools from attempting to construct a mud-brick bridge over the Mediterranean, YHWH decides to “confuse” (Hebrew balal) their language so they can no longer communicate one with another. Thus, they are forced to “spread abroad,” YHWH’s intent in the first place.

Luke, in his imagined Day of Pentecost, reverses the disaster at Babel by once again making it possible for all to hear the necessary words from God in their own language. The foolish tower builders have become in Luke’s literary vision the first knowledgeable converts to the Christian community, ready to live together in the power of God rather than challenging that power in their will to rule God’s world.

The goal of every preacher and teacher of God’s word, whether that be Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, or Sikh, is to speak the truth of God so that it can be understood by the hearers. This means far more than simply speaking that truth in the language of the hearers. Of course, if my hearers are first-Spanish speakers, I must speak to them in Spanish. But, each Spanish speaker has a unique history and background, a different education, different ways of accessing language, different cultural contexts— Guatemalan, Salvadoran, Mexican. If they are to hear “in their own language, all these concerns and more must be considered. The miracle at Pentecost means more than a simple language transmission; it means that in Luke’s miraculous portrait all assembled that day could genuinely hear, understand, and desire to live their lives in the ways that the Gospel of Jesus demanded.

As I have said in other places in my essays, I have preached and taught in over 1000 churches in my lifetime, and in each of those occasions I have attempted to make clear the power and truth of the gospel of God. But unlike the Day of Pentecost, very few of my hearers actually heard what I was trying to say, since both my speaking and their hearin g fell far short of the miracle needed to move hearers to hear, understand, and do as I hoped they would. In that sense, my ministry of preaching and teaching has been a clear failure. But I have the promise of Is.55 that the word of God will never return to God empty but will bring about what God has in mind for the world. Of course, the text does not promise when that fulfillment might occur! So you and I can never give up preaching and teaching what God has given to us, because that promise remains. Another Sunday comes, so preach and teach the truth of God, hoping that finally the Day of Pentecost might yield its harvest of believers and doers. Maybe this Sunday!

g fell far short of the miracle needed to move hearers to hear, understand, and do as I hoped they would. In that sense, my ministry of preaching and teaching has been a clear failure. But I have the promise of Is.55 that the word of God will never return to God empty but will bring about what God has in mind for the world. Of course, the text does not promise when that fulfillment might occur! So you and I can never give up preaching and teaching what God has given to us, because that promise remains. Another Sunday comes, so preach and teach the truth of God, hoping that finally the Day of Pentecost might yield its harvest of believers and doers. Maybe this Sunday!

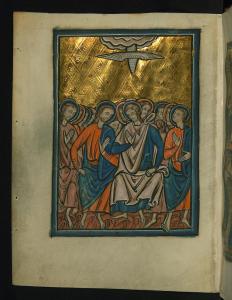

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)