I have long said that it is a crying shame that the same writer who penned (or chiseled?) the wonderful tale of Saul, David, and Samuel was not involved in the many stories that make up the complex books of Kings. They reek too often of that painful ideologue, the Deuteronomist, who was plying his editorial trade sometime after the obliteration of the northern kingdom of Israel (late 8th century BCE) and just before the total collapse of the southern kingdom of Judah (early 6th century BCE). The usual guess is that the beginning point of his writing was toward the former, and continuing toward the latter. We can finally never be more certain. His goal was, at least in part, to explore the reasons for the end of the two kingdoms of YHWH, and especially to pin the blame on the resolute evil of the various kings, particularly those monarchs of the northern kingdom who were deemed thoroughly evil, mainly because they did not worship in the only place where true worship could be celebrated, the temple in Jerusalem. Well, of course they didn’t! They lived in the north of the country and had their own central sanctuary at Bethel. Despite that historical fact, the one-sighted Deuteronomistic editor consigned them to the Israelite equivalent of Hell.

I have long said that it is a crying shame that the same writer who penned (or chiseled?) the wonderful tale of Saul, David, and Samuel was not involved in the many stories that make up the complex books of Kings. They reek too often of that painful ideologue, the Deuteronomist, who was plying his editorial trade sometime after the obliteration of the northern kingdom of Israel (late 8th century BCE) and just before the total collapse of the southern kingdom of Judah (early 6th century BCE). The usual guess is that the beginning point of his writing was toward the former, and continuing toward the latter. We can finally never be more certain. His goal was, at least in part, to explore the reasons for the end of the two kingdoms of YHWH, and especially to pin the blame on the resolute evil of the various kings, particularly those monarchs of the northern kingdom who were deemed thoroughly evil, mainly because they did not worship in the only place where true worship could be celebrated, the temple in Jerusalem. Well, of course they didn’t! They lived in the north of the country and had their own central sanctuary at Bethel. Despite that historical fact, the one-sighted Deuteronomistic editor consigned them to the Israelite equivalent of Hell.

Of course, he did not much like any kings, save the southern rulers, Hezekiah and Josiah, whom he called near saints for their attempts to cleanse the worshipping life of the people by removing the country-wide shrines to other deities and demanding exclusive worship in Jerusalem. Because his vision of the time was so restricted, his goal was less historical and literary than sharply ideological, and that is our loss. Instead of the richly complex and deeply human pictures of Saul, David, and Solomon, we get a too- saintly Solomon (albeit with a few exceptions like 1 Kings 11), a figure quite unlike the bloody palace schemer that we encounter in 2 Samuel. Consequently, the danger of teaching and preaching from the books of Kings is to be seduced by the editor into repeating his ideologically based account, nearly devoid of nuance. And reading the Bible without nuance is a decidedly dangerous activity. Just ask anyone who has been the target of biblical assaults from those who claim a “plain” reading: LGBTQ people, African- Americans, “liberals,” and a host of others. The beauty of nuance is that multiple readers can hear differently the same stories, and can thereby correct those who would hijack the text for their own dastardly purposes.

Still, as I said, on occasion in the books of Kings the ideological veil is lifted to allow a subtler story to appear. 2 Kings 2 presents one of those, even though the ideological goal remains in the forefront. In preparation for this tale of the passing of the prophetic torch from Elijah to Elisha (is it not a homiletical curse to have these names sound so much alike!), the quite superb stories of Elijah, filled with complex characterization and just enough magic to lure readers of all ages to them, are given to us primarily in 1 Kings 17-19, 21. There we find both a powerful and uncompromising prophet, yet equally a terrified and quite clueless one. After all, he runs for his life from the murderous Jezebel right after he has slaughtered all of her Baal prophets at the stream Kishon, at the base of the sacred mountain. When asked by YHWH in a cave on that mountain why he happens to be there, he replies by saying, twice, that though he has been a fabulous prophet, it is apparent that YHWH has abandoned him to his solitary fate. In response to that self-serving claptrap, YHWH demands that he return to the land and task that YHWH assigned to him in the first place, in effect telling the sniveling prophet that he should do less complaining and more prophetic labor!

Now, at 2 Kings 2, it has become time to pass the work of prophecy from the master Elijah to his mentee Elisha. There are numerous ways that such a story might be told. History records countless tales of students taking over the work of their teachers. In my own case, my Hebrew Bible teacher, both in seminary and graduate school, the finest reader of Hebrew that I ever knew, said to me over a hamburger lunch some years ago that I would in my own teaching life finally know what it meant to encounter a student who was better than I was. He seemed to be saying, however indirectly, that I was that student who was destined to go beyond the work of my teacher. I in no way have in fact done that, and still am convinced that my teacher’s work will remain unrivalled as teacher and mentor. However, I have had several students over my 36 years of formal teaching who have definitely moved well beyond my skills in many ways. In that sense, my teacher was right. In the case of Elijah and Elisha, however, it does not appear to be a case of the student outstripping the master. In fact, there exists in the story a decided notion that the student is destined not to be as great or as memorable as his teacher. Still, the story is a fascinating one and is well worth a careful look as a certain kind of teacher- student account.

Now, at 2 Kings 2, it has become time to pass the work of prophecy from the master Elijah to his mentee Elisha. There are numerous ways that such a story might be told. History records countless tales of students taking over the work of their teachers. In my own case, my Hebrew Bible teacher, both in seminary and graduate school, the finest reader of Hebrew that I ever knew, said to me over a hamburger lunch some years ago that I would in my own teaching life finally know what it meant to encounter a student who was better than I was. He seemed to be saying, however indirectly, that I was that student who was destined to go beyond the work of my teacher. I in no way have in fact done that, and still am convinced that my teacher’s work will remain unrivalled as teacher and mentor. However, I have had several students over my 36 years of formal teaching who have definitely moved well beyond my skills in many ways. In that sense, my teacher was right. In the case of Elijah and Elisha, however, it does not appear to be a case of the student outstripping the master. In fact, there exists in the story a decided notion that the student is destined not to be as great or as memorable as his teacher. Still, the story is a fascinating one and is well worth a careful look as a certain kind of teacher- student account.

Several conclusions may be drawn from the way the story is told. First, Elijah seems not to want Elisha to follow him on the journey that YHWH has called him to go. When he decides to respond to the call of YHWH to travel from Gilgal to Bethel, a very short trip of a few miles, he demands that Elisha “stay here” in Gilgal. But the student refuses loudly, swearing in the name of YHWH as well as on the life of Elijah, that he “will not leave you” (2 Kings 2:2). Two more times (employing the familiar rule of three from ancient folklore) Elijah bids Elisha stay in a place while he follows the commands of his God to move, first to Jericho, and finally to the Jordan river. Each time, Elisha refuses and follows his master.

There is a second feature of the story. Upon arrival in the new place some “sons of the prophets” (perhaps something like “prophetic colleagues”) confront Elisha and say, “Do you know that today YHWH will take your master away” (2 Kings 2:3, 5)? Elisha’s response to this apparent jibe is the same each time: “I know! Shut up” (2 Kings 2:3, 5)! I find this repartee between Elisha and his fellow prophets quite intriguing. It appears that the crowd of prophets, interested in seeing what is about to occur between the great Elijah and his would-be successor, are challenging Elisha’s worthiness to succeed the unique Elijah. Don’t you know anything, they shout? Elijah is about to ascend miraculously to YHWH and you, Elisha, are about to be quite alone in the work of the prophet of Israel. Of course I know that, you knuckleheads, retorts Elisha; do you think I am unaware of what Elijah is about to do and unaware of the plans of YHWH for him and for me? Shut up, the lot of you, he cries! In effect, Elisha appears to be saying that he is in fact the great Elijah’s worthy successor, since he is fully aware of what is about to occur, and despite his master’s continued attempts to leave without him, he has followed him to the very end and is prepared to undertake his work.

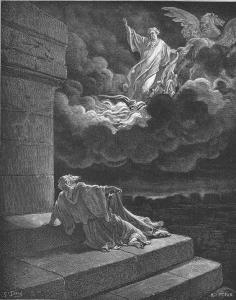

It is a very tiny literary flourish that we receive here, but it is a clever way of determining something about the end of Elijah’s work and the beginning of Elisha’s. In the subsequent dramatic scene of Elijah mounting a fiery chariot to YHWH’s heaven, and Elisha’s witness to the disappearance of his mentor in the clouds, the new prophet grabs the cloak of the departed Elijah and does the miraculous deed that he has seen Elijah do, namely the parting of the river Jordan, an obvious echo of the parting of the waters at the Sea of Reeds, as well as the later Jordan’s parting as the Israelites first head into the land of promise. We can imagine Elisha gazing triumphantly at the jealous band of prophets as the waters part at his command, shouting to them, “See! I told you I was worthy!”

Still, it must be said that the stories of Elisha recorded for us by the editors are in the main little like the wonderful tales of Elijah. There is no Naboth’s vineyard story of the oppression of the poor by the rich and powerful; there is no mysterious confrontation with YHWH on the sacred mountain. What there is seems decidedly pedestrian, if not downright horrifying and ridiculous: the prophet’s command for she-bears to maul some jeering children; the magic of a floating ax head and a never-ending cruse of oil. Elisha is far more magic man than Hebrew prophet; his most memorable act may be his command to the wild Yehu to murder the aged Jezebel.

Could it be that Elisha was finally not a fully worthy successor of Elijah? The next prophet we hear of is Amos, the unforgettable agent of YHWH, followed by the astonishing writing prophets of Israel. What the tales of Elisha may be are warnings that not everyone who claims the prophetic mantle is in fact worthy of the name. How well we 21st century religious types know that reality! We live in a century where any number of mountebanks claims the title prophet when in fact they are little more than dangerous frauds. The Deuteronomist tries in vain at Deuteronomy 18 to help us evaluate the trustworthiness of one who calls herself prophet; “if what the prophet says comes true, then she is a true prophet.” What else can one say to this definition of true prophecy but: absurd! I have no crystal ball to help me do what the old editor says I must do. Maybe Elisha was not far wrong in his reply to the jeering prophets: Shut up! It may be that we need to say that more often than we do to those who claim an office and a role that is not rightfully theirs. Also, we may also need to learn to say shut up to ourselves whenever we attempt to play the prophet well beyond our capabilities. Like Elisha, and his teacher Elijah, more humility would never be amiss.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)