(I am immensely grateful to Van Harvey, a former professor of theology at my school, Perkins School of Theology, for his succinct and probing analysis of this contested issue in his still valuable A Handbook of Theological Terms, 1964).

No self-respecting theologian, whether professional or not, can forever avoid the question of theodicy. The word itself is formed from two Greek words meaning “God” and “justice”. Hence, the issue refers to the attempt to justify the goodness of God in the face of the world’s manifold evil. It is perhaps fair to say that this question has driven more religious people to distraction or despair than any other faith concern. And if it hasn’t, it means that the question has simply not been raised. Of course, in non-monotheistic traditions, where multiple gods populate the pantheons of believers, say certain forms of Hinduism, the question is not so difficult. One can always blame the world’s evil on one god or another. But in monotheistic faiths, like Judaism, Christianity, or Islam, the problem is acute.

No self-respecting theologian, whether professional or not, can forever avoid the question of theodicy. The word itself is formed from two Greek words meaning “God” and “justice”. Hence, the issue refers to the attempt to justify the goodness of God in the face of the world’s manifold evil. It is perhaps fair to say that this question has driven more religious people to distraction or despair than any other faith concern. And if it hasn’t, it means that the question has simply not been raised. Of course, in non-monotheistic traditions, where multiple gods populate the pantheons of believers, say certain forms of Hinduism, the question is not so difficult. One can always blame the world’s evil on one god or another. But in monotheistic faiths, like Judaism, Christianity, or Islam, the problem is acute.

The problem may be stated succinctly as follows: either God is able to prevent evil and will not, or God is able to prevent evil and cannot. If the former is true, God is not merciful; if the latter is true then God is not omnipotent (all-powerful). Both possibilities raise bundles of conundrums. Certain classical attempts over the centuries have presented hoped-for solutions. Four general ones come readily to mind: 1) The world’s evil is caused by sin, defined in numerous ways, or by rebellion against God by some other deity or creature, perhaps an angel or a human being. 2) Evil is a necessary part of any finite order where beings are free, living in a fairly stable physical order. 3) Evil is actually an illusion of our temporal experience and would not even be seen to exist if viewed from the place of eternity (sub specie aeternitatis, according, for example to Spinoza). 4) There is finally no theoretical answer to the mystery of evil, and our only human response is obedience and trust in God’s goodness even if it is difficult to see such goodness in action.

It may be concluded that these responses attack one side of the dilemma (usually the side of omnipotence) or appeal to mystery. Let us look at each one in more detail. Responses 3 and 4 maintain the possibility of God’s omnipotence, but in actuality provide no real theoretical answer to the dilemma; that may satisfy some but hardly all of the questioners. 3 appeals to a viewpoint (“under the viewpoint of eternity”) that no human could ever have, while 4 merely says there is no answer save blind trust. 1 and 2 are in effect the same answer, since the former posits some evil power, whether divine or human, while the latter supplies the freedom in the world needed to rebel against God— even Satan is in the famous myth a fallen angel who purposely rebelled against his God out of jealousy or fury or some other motive depending on the telling of the myth. It should be said that most of the attempts to answer the issue of theodicy take some form of 2.

Under 2, there are multiple emphases: i) the self-limitation of God in creation; that is, God does not employ God’s overwhelming power but instead provides genuine freedom to God’s human creatures; ii) some deny the meaning of omnipotence in God and redefine the term; that is, they affirm that God is in fact not omnipotent, but instead is a necessary part of creation, albeit a significant and crucial part, but is profoundly affected by the actions of all creatures of creation; iii) some claim that God is definitely limited in power. As you can see, the problem has been in the main attacked at the point of God’s supposed omnipotence. If God is able to do many things, but not all things, then God’s goodness may be maintained and the existence of evil cannot be laid wholly at God’s feet, since there is real freedom in the universe, a freedom graciously granted by God.

Of course, a practical problem immediately arises in the face of this view of a limited God; is such a God finally worthy of our worship? This is, of course, less a theoretical concern than a worshipful one. Just why should I believe in and worship a God who is not in the end capable of acting as the omnipotent orthodox God of traditional faith? If that is troubling, then one in inevitably lead back to answer 4 above, and must simply trust that God is that God we need to act on our behalf out of divine goodness. But if we go that way, we find ourselves back into the dilemma of God’s power and goodness once again.

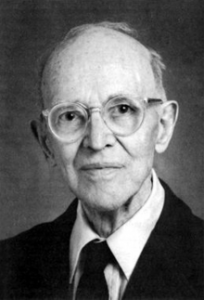

I admit that I am tempted to give in to that seductive number 4 and simply trust that God’s goodness will manifest itself in my life and the life of the world. Yet, I cannot be satisfied by such an answer, because God has given me a mind as well as a heart to use in response to God’s gift of my life. Hence, I am attracted to the response of the American philosopher, Charles Hartshorne (1897-2000), who, building on the work of Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947), said clearly that it was finally impossible to solve this ancient conundrum within the traditional framework of the classical view of God as both omnipotent and merciful. For Hartshorne, the concept of omnipotence is the problem. He claims that when speaking of God omnipotence can only mean a power to determine the conditions of a world that maximize the opportunities for desirable decisions by free and finite humans. This, by necessity, assumes risk, both on the part of God and on the part of the humans. It creates possibilities of joy, creativity, happiness, but also greater possibilities of tragedy and pain.

I admit that I am tempted to give in to that seductive number 4 and simply trust that God’s goodness will manifest itself in my life and the life of the world. Yet, I cannot be satisfied by such an answer, because God has given me a mind as well as a heart to use in response to God’s gift of my life. Hence, I am attracted to the response of the American philosopher, Charles Hartshorne (1897-2000), who, building on the work of Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947), said clearly that it was finally impossible to solve this ancient conundrum within the traditional framework of the classical view of God as both omnipotent and merciful. For Hartshorne, the concept of omnipotence is the problem. He claims that when speaking of God omnipotence can only mean a power to determine the conditions of a world that maximize the opportunities for desirable decisions by free and finite humans. This, by necessity, assumes risk, both on the part of God and on the part of the humans. It creates possibilities of joy, creativity, happiness, but also greater possibilities of tragedy and pain.

Hartshorne’s answer sounds a good deal like 2i above, but what he adds is his insistence that God as limited creator in fact suffers along with God’s creatures. All tragedies of existence, both human and animal, are deeply known and deeply felt as tragedies in the life of God. Thus, for Hartshorne, the traditional conceptions of God, namely that God is both omnipotent in the classical definition and disinterested in the suffering of God’s creation, are both quite false. What we have then is a God who graciously provides real freedom for God’s creatures, and at the same time a God who takes up into the divine life both the joys and the sorrows of all beings. God then grows larger and more compassionate with God’s creation and bids all of that creation to grow similarly. This may all sound quite strange to those of you who have long embraced the traditional notions of classical theism, but for me I find vast comfort in conceiving of a God who creates, offers freedom, and suffers and loves along with me as I attempt to become more the creature that God wants me to be.

This is hardly the only way to conceive of the mysterious and wonderful God we strive to worship, but I offer this too brief look at another way to see God in the hope that it opens you up to fresh possibilities in your own life of faith.

(images from Wikimedia Commons)