I have been using a lectionary list that includes two complete Hebrew Bible texts, so this week I want to address an enormously influential pericope from a book I know very well. I wrote a long, and essentially unreadable, dissertation on the book of Job in 1974, published a book, Preaching Job, in 1999, and have spoken about the book in numerous settings throughout my scholarly life. I absolutely love this book, and regret very deeply that it has played a too small role in the ongoing work of theology both in the synagogue and the church. To reduce the thing to “the patience of” is to trivialize it beyond all recognition. In a similar vein, to suggest that its “point” is to address the vexed issue of “innocent suffering” is to me to miss the far more important issues the author is attempting to raise. And to imagine that what the book says is “the final reward of a supremely faithful believer” is just plain wrong. I believe that Job’s author was most deeply concerned with the nature of God, especially as that question arose with existential power in the Babylonian exile of Israel. I am well aware that there is little internal or external evidence that the book was in fact composed during that period, but I have long held that assumption since that special time in the history of the people of Israel offers the most suggestive time for its composition. We can be quite certain that the book of 2-Isaiah was written during this period, and it seems clear that, among other things, Job was a kind of counter-answer to Isaiah’s convictions about YHWH. What I have to say in this essay will assume that the exile is the crucible for the author of Job.

I have been using a lectionary list that includes two complete Hebrew Bible texts, so this week I want to address an enormously influential pericope from a book I know very well. I wrote a long, and essentially unreadable, dissertation on the book of Job in 1974, published a book, Preaching Job, in 1999, and have spoken about the book in numerous settings throughout my scholarly life. I absolutely love this book, and regret very deeply that it has played a too small role in the ongoing work of theology both in the synagogue and the church. To reduce the thing to “the patience of” is to trivialize it beyond all recognition. In a similar vein, to suggest that its “point” is to address the vexed issue of “innocent suffering” is to me to miss the far more important issues the author is attempting to raise. And to imagine that what the book says is “the final reward of a supremely faithful believer” is just plain wrong. I believe that Job’s author was most deeply concerned with the nature of God, especially as that question arose with existential power in the Babylonian exile of Israel. I am well aware that there is little internal or external evidence that the book was in fact composed during that period, but I have long held that assumption since that special time in the history of the people of Israel offers the most suggestive time for its composition. We can be quite certain that the book of 2-Isaiah was written during this period, and it seems clear that, among other things, Job was a kind of counter-answer to Isaiah’s convictions about YHWH. What I have to say in this essay will assume that the exile is the crucible for the author of Job.

The text for today is justly famous, but I think it has been quite seriously misunderstood. Allow me to translate the text once again so that you may see the difficulties of the language along with the complexities of its understanding.

(23)“If only my words were written down!

If only they were inscribed in a book,

(24)with iron pen and lead chiseled on a rock forever! (25)Because I know that my vindicator is alive,

and finally will stand on the earth.

(26)And after my skin has been flayed off,

With (or “without”) my flesh I will envision God (Eloah), (27)Whom I shall envision myself!

My eyes will see, not some stranger’s.

My inward parts are thrilled!”

If you are comparing what I have translated to other published readings, I am certain you have noted some stark differences, many of which are quite significant. For this essay, I wish to focus on only one.

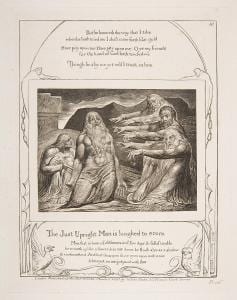

The word I have read “vindicator” in vs.25 is more popularly read as “Redeemer” and is regularly capitalized (see NRSV). Of course, all classical Hebrew is capitalized, so an English capitalization is an editor’s decision. I can only assume that the NRSV translators have followed long custom here by capitalizing the word, matching the 1611 KJV’s reading that has been forever enshrined in our ears by Handel’s immortal “Messiah” in the soprano aria that begins part three of that great work. The capital letter assumes that the reference is either to God or Jesus. Many Christian commentators assumed the latter for centuries, while other readers assumed the reference was to God. The author of Job, writing in the 6th century BCE did not have Jesus in mind, though he could have been thinking of God as Job’s redeemer. After all, the Hebrew word, go’el, is certainly one of 2-Isaiah’s favorite designations for God; he uses it no fewer than 10 times in his 16 chapters. However, I find the notion that Job uses go’el as a reference to the God of Israel fatuous on obvious literary grounds. Earlier in Job 19 Job has excoriated God as his enemy, one who has “put him in the wrong” (19:6), has “darkened his way” (19:8), has “stripped away his glory, tearing the crown from his head” (19:9), has “uprooted hope like a tree” (19:10), has “kindled fury against” him (19:11), has “sent troops against” him, “erecting siege works (if that is the meaning of the word) against” him, etc. In short, God has made Job out to be enemy (19:11b), not his vindicator or redeemer at all. Why would Job suddenly turn to God for help, expecting God either to vindicate or redeem him?

There is another meaning of this Hebrew word found in the book of Numbers 35, especially vss.12, 16-21. There the go’el is the avenger of blood. This office was apparently an established one at some times in the history of Israel. His role was to roam the community and offer strict and swift justice whenever violent murder had occurred. Murderers who strike with intent to kill, whether with iron, stone, or wood, shall face immediate execution by the avenger of blood. Anyone who with clear intent “pushes someone out of hatred, or hurls something at another, lying in wait, and death ensues” (Num.35:20), may expect the vengeance of the avenger of blood. I would suggest, as terrible as it may at first sound, that this may be what Job has in mind at 19:25, namely the rise of the avenger of blood who will exact vengeance on this God who has humiliated and attacked Job for no discernible reason.

Job in this small section imagines that he has in fact finally died at the hands of this monstrous deity, his skin having been flayed off at the last, but because his indictment of God has been “engraved in a rock forever,” and will never be effaced, the avenger of blood will read the charge, will confront the killer, and, like some sort of ancient gunfight at OK corral, will play the role of Job’s avenger and slaughter God. And Job himself will witness this fight (the NRSV’s reading “whom I shall see on my side” is not persuasive, although if the avenger of blood is meant, it could be part of the scene); “I will see for myself,” he says.

Such a reading may sound like the ravings of some sort of atheist—a killer of God indeed! However, I suggest that the movement of the plot of Job makes this understanding plausible. At Job 9:33, Job had said, “If only there were an umpire between us,” hoping that some impartial arbiter might settle the struggle that Job is having with the God he thought he knew. After all, he and the friends both believe that God does indeed reward the righteous and punish the wicked. The difference between them is that the friends, because they believe Job to be evil, think that God is doing precisely that, namely punishing the evil sinner Job, while Job does not accept that he has done anything worthy of the assaults from God that he has received; hence God has in his case made some sort of mistake or is finally a random sadist, destroying both righteous and wicked indiscriminately (Job 9:22-24).

Then, after the dialogue between Job and his so-called friends ratchets into deeper kinds of fury, Job turns again to some sort of arbitrator at Job 16:18-21, in this case a “heavenly witness,” a kind of prosecutor who will take Job’s case, drawing God into a court, and advocating on Job’s behalf. Apparently, the hope of an impartial umpire (Job 9) has evolved into a heavenly attorney who will attempt to win the case for Job against God. And finally at the end of the second acrimonious dialogue with the friends, and after Job has attacked his God as cruel and despotic and silent in the face of his pain, I suggest that his third request for outside help results in the call for the avenger of blood who will finally end his case with the murder of the problem, namely God, or perhaps better said, the murder of god, small “g”, in fact no real God at all.

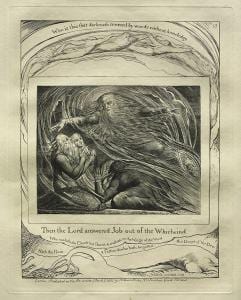

I say that this god needs killing! Any god who rewards the righteous and punishes the wicked is finally no God at all. One of the chief goals of the book of Job is to murder that god for all time, as the false god it surely is. The universe, the author wishes to say, does not operate on the basis of divine calculus, a kind of zero sum game where some win and others lose. The universe of God is both far more than that and far more mysterious than that. The God we see in the great speeches of Job 38-42 does not at all resemble such a mechanistic deity but instead has created a world filled with surprise, a world that does not place humanity at its center but offers humanity a place in it along with “lion, tigers, and bears” and wind, snow, and ice. We need to expunge from our thinking forever this idea of a rewarding/punishing God. Such a god does not exist and never did. That god needs killing, and the wild imagination of Job has done just that.

(images from Wikimedia Commons)