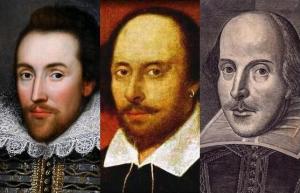

As I have revealed in earlier essays, I am a great lover of William Shakespeare, that greatest of authors in the English language. Earlier in my scholarly life, I had hoped to teach the bard in some place or another, but my vocation as scholar took me in quite different directions. Still, I never fail to thrill to these grand works, and never fail to be in absolute awe of their mastery, their wit and insight. There is so much in the plays and the sonnets to compass that several lifetimes would fail in the attempt.

As I have revealed in earlier essays, I am a great lover of William Shakespeare, that greatest of authors in the English language. Earlier in my scholarly life, I had hoped to teach the bard in some place or another, but my vocation as scholar took me in quite different directions. Still, I never fail to thrill to these grand works, and never fail to be in absolute awe of their mastery, their wit and insight. There is so much in the plays and the sonnets to compass that several lifetimes would fail in the attempt.

I have generally been attracted to the tragedies among the plays; Macbeth always sends shivers up my spine to witness the horrors of untrammeled ambitions. Hamlet’s continual mysteries—why finally cannot the melancholy Dane do his appalling uncle in?—have been a source of deep pleasure and hard thought for decades. Othello’s gullible, green-eyed jealousy has perplexed and at the last moved me for its utter waste of glory and love. I could go on, but I will spare you more of my amateur musings.

I have only of late turned to the history plays, and especially to the two Henry IV’s, meditations on England’s colorful canvas and reflections on the major players that fill the scenes. From John II’s forced abdication of the crown to the potent figures of Bolingbroke, who becomes Henry IV, seizing power with the help of a coalition, too soon shattered, and then to Henry V, who became legendary for his defeat of the French at Agincourt against overwhelming odds. This is history writ very large, history as much myth as fact, but all the richer for it. It might better be said that Shakespeare uses the backdrop of history to meditate on more universally human themes, as kings and princes are shown to us as fully human, great but flawed, larger than life but all too human for all that.

The two Henry IV plays are in fact about the relationship of fathers and sons, as Shakespeare tells it. In Henry IV, part 1, we learn that the aging Henry IV has a son that he wishes he had never had. He is known as Harry or Hal, and he is in effect a wastrel, spending much time with a passel of cronies in a pub, The Boar’s Head, in Eastcheap, the seediest part of London. Chief among the friends of Hal, who is the Prince of Wales and heir to the throne, is Sir John Falstaff, a drunken, immensely fat man, though a superb improvisational wit, a debauched genius of sorts. At the same time, this knight simply can never be trusted, since he spends his days drinking copious amounts of sack and devouring untold numbers of capons, while he devises cunning and calculating schemes that lead always to the exploitation of others. He is a thief, robbing pilgrims returned from Canterbury. And when he in turn is robbed for a lark by none other than Hal and his friend, he claims to have known that his, Falstaff’s robber, was in fact the Prince of Wales all along, though he ran from them as the coward that he is. In short, Falstaff’s grand schemes, imagined wealth, and fantasies about a future of power as duke or earl, bestowed to him by his bosom friend, the prince, when he becomes king, come to nothing. This is so, because Falstaff, though clever and witty, has squandered both for foolish gain, and ends with nothing. He may think he is Hal’s adopted father, but he is in reality merely a rogue, a mountebank, a vast mountain of windy flesh.

In one of Shakespeare’s most devastating scenes, Hal, having become the king after reconciling with his true father before that father’s death, repudiates the old and pathetic Falstaff on the way to his coronation. Falstaff, now convinced that his old friend will reward him with power and glory, confronts Hal, now Henry V, as he marches up the great Abbey at Westminster to be crowned king. “God save thee, my sweet boy,” bleats the man. “I know thee not, old man. Fall to thy prayers. How ill white hairs become a fool and jester! I have long dreamt of such a kind of man, so surfeit-swelled, so old, and so profane. But being awake, I do despise my dream” (2 Henry IV, 5, 5, 41, 45-49). Henry V then has Falstaff conveyed to prison for the thief that he is.

It is true that Henry IV had repudiated his eldest son, preferring instead another Harry, one Harry Percy, also know as Hotspur, a raging and active man who prefers the field of battle and the glory of intrigue above all else. Though Henry IV muses at the play’s beginning that he wishes the two boys had been switched at birth, leaving him with Hotspur for a son, it proves all too soon that Hotspur is a traitor to the king and must be confronted on the battlefield if Henry’s England is to survive. Hal, Henry IV’s true son, finds Hotspur alone on the field of war, and after a long struggle, kills him, thus proving his value both as future king and as his father’s son.

A truly terrible event occurs after Hal kills Hotspur. Falstaff, hiding from all fighting, and pretending to be dead in the battle, in fact witnesses the death of Hotspur. He then goes over to the corpse and thrusts his sword into Hotspur’s dead leg. He hoists Hotspur’s body onto his shoulders, and carries him back to the victorious Hal, claiming that he it was who killed Hotspur after an hour-long struggle. Hal knows this to be a gross lie, but saves his condemnation for the scene I mentioned above.

Just who is Falstaff in these plays? This has been the stuff of much debate among the scholars, but I think a partial answer may be provided in a remarkable speech of the fat knight in the midst of a hilarious play within the play between Hal and Falstaff wherein each play the roles of Henry IV and Hal both in two separate playlets. While Hal plays his father, he moves to banish Falstaff from his life and person. Falstaff replies, in part: “but for sweet Jack Falstaff, kind Jack Falstaff, true Jack Falstaff, valiant Jack Falstaff, and therefore more valiant being, as he is, old Jack Falstaff. Banish not him thy Harry’s company, banish not him thy Harry’s company. Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world” (2.5.431-38). How this scene is played determines in large measure who Falstaff is portrayed to be. If it is merely disingenuous, ironic jesting—“surely you would not banish me, a paragon of human virtue”—then it lies on the surface of human relationships. But if there is a wistfulness, a fear that it could happen, a banishment means more than the loss of future glory for the old knight. Banishment can mean that such a man, one who is rarely sweet and kind and true, and never valiant, save in eating and drinking, can be overcome, can be discarded for something far better, for someone who is all those things and more. I think Falstaff in the play is the darker side of humanity, a prodigious liar and thief, a clever wit whose wit has been wasted on sack and lies, whose dreams are unworthy because based on taking advantage of others, rather than on one’s good and kind works.

All of us have some Falstaff in us, if we can face up to it honestly. We are fathers who have too often wheedled our ways into our fathering, rather than turned to kindness and fairness and honesty in dealing with our sons (and daughters). We who are sons have too often made the jest with our fathers, have not treated them as the serious fathers they wanted to be, but perhaps did not know how. We have not faced our responsibilities and have allowed our fathers not to face theirs. It is crucial that we grow up as sons and fathers, turning to our lesser selves and say, “I know thee not, old man; fall to thy prayers!” Until we banish old Jack, we will continue to waste our gifts on capon and sack, never becoming what Shakespeare and God want us to be, namely, fully formed human beings, willing to tell truth and live in kindness and honesty.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)