I have just finished a fascinating book by Aviya Kushner, called The Grammar of God. Kushner combines something of a memoir with her serious engagement with the Hebrew Bible in translation. Her story is quite unique. She was raised in a near all-Jewish enclave, Monsey, New York, a brief distance from Manhattan. Almost all the residents of the town are Chasidic Jews of various kinds; Kushner’s family was not Chasidic, but was a very serious practitioner of Orthodox Judaism. Her father was a professor of mathematics, while her mother was a lover of ancient languages, from Akkadian to Ugaritic to Syriac. They spoke Hebrew in the home, and Aviya read the Hebrew Bible only in Hebrew, never reading it in any other language until she became an adult.

I have just finished a fascinating book by Aviya Kushner, called The Grammar of God. Kushner combines something of a memoir with her serious engagement with the Hebrew Bible in translation. Her story is quite unique. She was raised in a near all-Jewish enclave, Monsey, New York, a brief distance from Manhattan. Almost all the residents of the town are Chasidic Jews of various kinds; Kushner’s family was not Chasidic, but was a very serious practitioner of Orthodox Judaism. Her father was a professor of mathematics, while her mother was a lover of ancient languages, from Akkadian to Ugaritic to Syriac. They spoke Hebrew in the home, and Aviya read the Hebrew Bible only in Hebrew, never reading it in any other language until she became an adult.

She is also a journalist and poet, having lived in numerous countries, making her living primarily as a writer. While living in Iowa, pursuing a degree at the prestigious Iowa Writer’s Workshop, she enrolled in a class in Bible reading with the esteemed novelist, Marilynne Robinson. For the first time, she encountered the Hebrew Bible in English, and that encounter set her on the course that produced this book. It is in brief a summary of her multiple and complex reactions to reading her beloved text in English, and her doing so among many Christians, both Catholic and Protestant. Just as her eyes were opened to the numerous ways that the Bible in translation has affected the non- Jewish culture that she was now discovering, so my eyes were opened as I compared my own very different experience with the Hebrew Bible with hers.

I was raised in an exclusively English-speaking household, and had no real exposure to the Bible in my early years. I did not take the Bible with any seriousness until I went to seminary in 1968 and took Hebrew as a kind of lark—it looked funny, so why not? I fell in love with the language and the culture it represented, and have maintained my love affair for the past 52 years. I am sure that my Hebrew prowess pales in the light of Ms. Kushner’s, but I can read the language well enough to know how little I really know about it. Among many things one may learn by reading her book is that reading the Hebrew Bible in Hebrew is a never-ending, endlessly fascinating and frustrating romp through texts that bristle with beauty, humor, and fulsome ambiguities. As she states again and again, there is finally no end to the task of reading that the Bible presents to those who enter its wonders; in short there can be no definitive, final readings of this text.

And that is a fact that too few Christian readers take with the seriousness that they ought. My fundamentalist friends—yes, old liberal me has a few of those—bark up the wrong Edenic tree when they imagine that the last word of translation has been spoken, and that now they can sit back and interpret what they have at last mastered. Anyone who reads Hebrew at all knows full well that the very first words of the Hebrew Bible are fraught with numerous pitfalls for the translator. Does the grammar of the first three verses of Genesis imply one long sentence, all hinged on the rendering of the very first word (“In the beginning?” or “In beginning?” or “something like “When God began to create?”), or are there two or three separate sentences, again dependent on various possible translations of the first word? One of those above-named friends was a fine reader of Hebrew, banded with a PhD from Harvard, no less, who said to me with a straight face, “Well, John, I know the grammatical difficulties of Gen.1:1-2 very well, but I also know that the perfect text, without confusion or ambiguity, is laid up in heaven.” “But,” I replied, “I cannot read that one; this is all we have!” He smiled, and said, “Some day, John, some day, all will be revealed.” And so it may, but for now we are stuck, or in my mind rather, blessed, with this delightful and challenging ancient text. How glad I am to be faced with its inconclusiveness and uncertainties! It makes for a rollicking good time whenever I approach it.

Let me give a brief example of the fun. For those of you who do not read Hebrew, I hope you can still catch a glimpse of the joy I find in my attempts to read. I was recently translating Exodus 32, that marvelous tale of the molten calf, and the hilarious confrontation between Moses and his nemesis, sometimes brother (the full story of the pair is not always clear about their relationship), Aaron. Yet, the translation fun begins in the very first verse of the story. The NRSV, a typical reading, translates Ex.32:1 “When the people saw that Moses delayed to come down from the mountain…” The verb rendered “delayed” is a participial form of a verb that nearly always means “to be ashamed” (bosh). The various noun forms built from the verb all mean “shame.” Only at Judges 5:23 might this same form be translated “delay.” In the face of the overwhelming meaning of “shame,” why do we find but two possible renderings of “delay?” Of course, it fits the context, both here and in the Judges passage to suggest a meaning of “delay,” but might the more common meaning of the word play a role in what is being said here?

Could it be that the narrator of Exodus 32 has both a suggestion of delay as well as the whiff of shame in Moses’s apparent refusal to return from his chat with YHWH? After all, the people will say to Aaron, “As for this Moses (using a demonstrative pronoun “this” as a way of indicating their anger and confusion at the man), we do not know what it is to him” (I read very literally). This odd phrase appears to mean something like “we do not know what is up with the man.” Of course, they know perfectly well that Moses is on the mountain talking to their YHWH, but the delay has in their minds become shameful. Moses is not only delaying his return; he is shaming himself and them by his delay. In this subtle way, the narrator allows a look into the minds of the people, and what we see there prefigures the coming disaster of calf-making and “running wild” (Ex.32:25, employing a verb that sounds suspiciously like the word for “pharaoh,” an echo of YHWH’s angry use of the phrase “stiff-necked,” found earlier in Exodus specifically to define the actions, or better inactions, of the Egyptian monarch).

That is merely one example of many that could be enumerated in this one chapter of the superb artistic abilities of the person who created this text. Indeed, translation delights may be found all over the Hebrew text, even in seemingly simple texts like Deuteronomy or the books of Chronicles. But those will need to wait for another day’s essay.

Whenever I go to preach and teach in a congregation, I am regularly asked two questions: which translation should I be reading and why don’t you, John, do your own translation? My usual answer to the first is to choose one or the other committee translations [NRSV, Jerusalem (JB), Jewish Publication Society (JPS)]. I now add the singular, and very insightful work of Robert Alter and Everett Fox, both attempts to translate the Hebrew with an eye on its literary insights. As for the second question, I answer something like this: “If I were to translate the Hebrew Bible, it might come out about 100 volumes long, each page headed by a sentence from the text, followed by 50- 100 footnotes, detailing the possibilities of translation, or at least some of them.” Since I am now nearing 74 years of age, I will now never live long enough to complete such a thing.

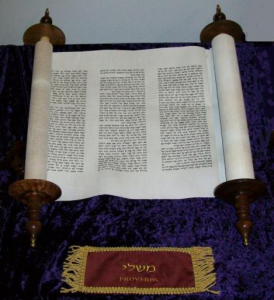

I avow that the greatness of the Hebrew Bible is to be found in its rich details. The Rabbis were surely right to take seriously every word, every letter, every vowel point, even though those vowels were not added to the text until the 7th or 8th century CE, bringing great help for new readers of Hebrew, but also creating perhaps more confusion concerning the meaning of more than a few words. As Kushner reminds us, when the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew text, was produced sometime in the 3rdcentury BCE, under the fear that the text might be lost in an increasingly Greek-speaking world, the rabbinic manuscript Megilat Ta’anit Batra, a pre-Mishnaic scroll, writes, “On the eighth of Tevet, in the days of King Ptolemy, the Torah was written in Greek and darkness descended on the world for three days.” Translation is necessary, as languages and cultures change, but as the poet Chaim Bialik once described translation, “it is a kiss through a handkerchief.” Most of us necessarily continue to kiss the Hebrew text as through a handkerchief, but we must always remember that a truly satisfying kiss, if we have ever experienced one, can only occur when the handkerchief is removed. I am grateful for those deeply devoted scholars who have spent their lives translating the Hebrew Bible and thereby giving it to us in language we can access. Yet, translation is forever and always something lesser, something finally dissatisfying, something that both reveals and obscures the treasures that only the language itself can offer. And even that, the language itself, both reveals and obscures, but such is its greatness that we still, millennia after its creation, stand in awe of its vast, unfathomable wonders.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)