I write this article at the end of a fascinating political week. This past Tuesday 14 states held their presidential primaries, the result of which vaulted Joe Biden to the head of the Democratic pack. Various adjectives were employed by the pundits to describe Biden’s rise from the ashes of almost certain defeat after his dismal showings in Iowa and New Hampshire; in fact, many of those same pundits had consigned Joe to the dustbin of history and had anointed Bernie Sanders as the presumptive nominee. But now “astonishing,” “unprecedented,” and “amazing” were qualifiers employed to describe the now ascendant Senator from Delaware. What a difference a few days can make! The Democrats now face a real two-person old white man’s dogfight for the nomination, pitting one 78-year-old Senator against another 77-year-old Senator. All the women candidates, save Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, have dropped out, including my choice, Elizabeth Warren. Why that happened has much to do with obvious misogyny, among other factors. But that is the subject for another day.

I write this article at the end of a fascinating political week. This past Tuesday 14 states held their presidential primaries, the result of which vaulted Joe Biden to the head of the Democratic pack. Various adjectives were employed by the pundits to describe Biden’s rise from the ashes of almost certain defeat after his dismal showings in Iowa and New Hampshire; in fact, many of those same pundits had consigned Joe to the dustbin of history and had anointed Bernie Sanders as the presumptive nominee. But now “astonishing,” “unprecedented,” and “amazing” were qualifiers employed to describe the now ascendant Senator from Delaware. What a difference a few days can make! The Democrats now face a real two-person old white man’s dogfight for the nomination, pitting one 78-year-old Senator against another 77-year-old Senator. All the women candidates, save Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, have dropped out, including my choice, Elizabeth Warren. Why that happened has much to do with obvious misogyny, among other factors. But that is the subject for another day.

Today I am interested in how quickly life can change. Mark’s gospel majors in rapid change, in the demand for making choices, in Jesus’s unflinching desire that we follow him, the one who has come to represent his God most fully to those of his day and of our day, too. Mark 12 begins with one of only two lengthy parables that are to be found in his telling of Jesus’s story; the other is the parable of the sower in Mark 4. Here we read of a vineyard and how brutally the farmers who have leased the vineyard from an absent landowner treat a succession of messengers sent by the owner to collect his rightful share of the crops. Two slave messengers are beaten, while a third is murdered. Other slaves are sent, but each in turn is either assaulted or killed. Finally, the owner sends his own son, believing “surely they will show this son of mine some respect” (Mark 12:6). Instead, when the son comes to collect his father’s share of the produce, the farmers see their opportunity to kill the son, the heir of the property, imagining that with the son dead, they will be the inheritors. As a result of that thinking, they murder the son and throw his body out of the vineyard. The story ends with the fearful conclusion that the owner “will come in person, and do away with those farmers, and give the vineyard to someone else” (Mark 12:9). A well-known Passover reading from Psalm 118:22-23 caps the dark tale: “A stone that the builders rejected has ended up as the keystone” (Mark 12:10).

Given the ending of Mark’s gospel, the point of the parable is more than obvious: Jesus has come to relay the demands of his God, and the result will be his murder at the hands of the current occupants of the vineyard. Of course, in the Hebrew Bible the metaphor of a vineyard was often used as an announcement of the fate of the land of Israel, most famously in Isaiah 5:1-7 (but see also Jer.2:21 and Ez.19:10). Immediately following the parable, “they” (clearly Jesus’s opponents) keep looking for some way they can grab the troublemaker, and get him out of their hair, but they were stymied by the sheer size of the crowds around him, even though they knew that the nasty story he had just told was aimed squarely at them.

So instead of grabbing him physically, they decide to act in a more subtle way to ensnare him, sending some Pharisees and Herodians “to trap him in a riddle” (Mark 12:13). The two parties named are the same duo that plotted against Jesus’s life in Mark 3:6. In addition, the Herodians in the meantime have murdered John the Baptizer (Mark 6:17-29). Of course, nearly all of the early followers of Jesus were Pharisees, the progressive Jewish party of 1st century Palestine, while the Herodians are obvious supporters of those in power and can hardly be expected to find Jesus anything less than a pain in the neck. The “riddle” they ask him is designed specifically to trap him; the question they ask is obviously loaded.

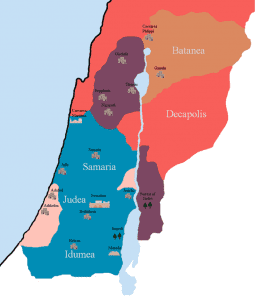

They begin with a smarmy bit of flattery. “Teacher, we know that you are honest and impartial, because you pay no attention to appearances, but instead teach God’s way forthrightly” (Mark 12:14). They first announce to the assembled hearers that they know what is most important about Jesus, the teacher, namely that he is honest and impartial, and thus can be trusted to answer their question straightforwardly and without cleverness or guile. In short, they set him up to trap himself in his own words. “Is it permissible to pay the poll tax to the Roman emperor or not? Should we pay or should we not pay” (Mark 12:14)? The question is offered as a simple one, a yes or no sort of query. Of course, it is hardly simple at all. The infamous poll tax of Rome was instituted in 6CE, imposed on the population of Judaea, Samaria, and Idumaea when they became a Roman province under the rule of a procurator. Such a tax, designed primarily to fund the army of occupation, could only be a source of fury for the Jews, since it was still one more sign that Rome interfered with Jewish sovereignty in any way they could. This same tax boiled over into revolt under Judas, referred to in Acts 5:37, and if Josephus is to be believed in his Antiquities, it also brought about the rise of the Zealot movement, leading eventually to the vast revolt of the Jews against Rome in 70CE. Thus, the question of the payment of this tax was a burning one.

The question urged Jesus to choose whose side he was on: an answer that suggested the payment of the tax would announce that he sided with Rome, and would thus cause a serious loss of support from the more rebellious portions of the population. But if he attacks the payment of the tax, he can be denounced to the Roman authorities and arrested as a political agitator. Damned if he does, damned if he doesn’t. A seemingly perfect trap! Jesus’s answer is not so much clever, although it is that, as it is inevitable, given who Jesus is. “Let me have a look at the coin,” he says. The poll tax could only be paid in Roman coin, the infamous silver denarius, not in the smaller copper coins in everyday use in Palestine. The denarius had the emperor’s head fixed upon it. Without hesitation, the questioners produce one of the coins, suggesting that they are ready to pay the tax to Rome. Of course, by Jewish law and custom, Jews may not carry anything that has a supposed god’s or human image on it; in that way the Herodians and Pharisees have broken their own laws. “Why, look at the picture on this coin,” says Jesus. It is no one but the emperor’s likeness, they admit. So, Jesus cries, “Pay to the emperor what belongs to the emperor” (Mark 12:17), suggesting at first that he has sided with the Roman authorities. One, after all, cannot escape the demands of the emperor.

However, Jesus has not finished his reply. “Give to God what belongs to God,” he concludes. “And they were dumbfounded at him” (Mark 12:17). This part of the reply has long been used to say that all should follow all the laws of the state, a kind of “two kingdoms” belief that each citizen of a state owes allegiance to that state, and must therefore pay their taxes and follow the laws, even if they are followers of God. It might be read like that, but I wonder if another more radical reading is possible. “Give to Caesar what belongs to Caesar and to God what belongs to God.” But if all belongs to God, nothing in effect belongs to Caesar! Thus, far from urging following state law, what Jesus may be suggesting is that if one really gives to God what belongs to God, and if state law hinders that action, then disobeying certain laws of that state may be not only appropriate but necessary if God is to be obeyed. Surely, when protesters against state laws forbidding black people from being served in certain restaurants in the 1950’s, were arrested, one would now hardly argue, I hope, that such laws should always be followed in 2020, quoting Mark 12 as rationale.

Jesus’s listeners that day were “dumbfounded” not only because Jesus has cleverly tricked the would-be tricksters, though that may be partly true. What is finally dumbfounding is the radical claims that this person continues to make with regard to the demands of God and the reworking of the community of humanity. Change is afoot, and those who are prepared to envision that change and to live into it, may certainly experience life in ways far different than it has been experienced up to now. Whether Biden or Sanders is Democratic nominee against Trump in November will not be the decisive change we all may see. One election, one silver coin, one clever reply does not constitute change. Change will only occur when we, unlike the temporary occupants of the vineyard, finally discover more exactly what it means to give all that belongs to God to God and not to any emperor or prime minister or president.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)