As we approach the holist days of Christianity, I have been led to think again about the texts on which these celebratory days are based. Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter find their roots in specific biblical texts from the New Testament, themselves rooted in certain texts from the Hebrew Bible. As both pastor and teacher for more than 50 years, I have regularly this time of year turned to these texts that speak to what Christians most basically believe about Jesus and what his ministry actually may mean for modern believers. However, I readily admit that the more I study these texts the more I am led to think freshly about that possible meaning. This is so because of the nature of the texts themselves.

As we approach the holist days of Christianity, I have been led to think again about the texts on which these celebratory days are based. Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter find their roots in specific biblical texts from the New Testament, themselves rooted in certain texts from the Hebrew Bible. As both pastor and teacher for more than 50 years, I have regularly this time of year turned to these texts that speak to what Christians most basically believe about Jesus and what his ministry actually may mean for modern believers. However, I readily admit that the more I study these texts the more I am led to think freshly about that possible meaning. This is so because of the nature of the texts themselves.

I recently finished the superb trilogy of books by the English writer, Hillary Mantel, retelling the story of Thomas Cromwell, the second most powerful man in England during the closing days of the reign of the infamous Henry VIII in the middle of the 16th century. There is very little actual history available concerning this important figure—his birth to a blacksmith in Putney in 1485, a portrait or two, some letters, some contemporary commentary, usually negative, about him—along with the absolute certainty that he was executed in Henry’s favorite way by losing his head on Tower Hill on July 28, 1540. In about 1600 scintillating pages, written over 12 years, Mantel has brought Cromwell back to life in a tour de force of fabulous prose based on careful research but far more on an unmatched imagination. This is historical fiction at its brilliant best.

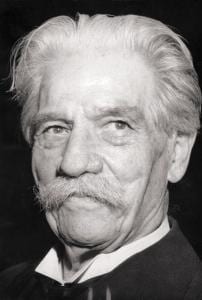

I have come to believe that when we read the Gospels of the New Testament, we are in fact reading historical fiction. The authors of the four pieces have taken threads of information about the man Jesus, some of which may contain grains of historical truth, and some of which certainly are made-up well after his life ended, added their own rich imaginations, and have created the central documents of Christianity. For me, the various quests for the actual historical Jesus that began in the 18th century in Germany, led by H.S. Reimarus and David Friederich Strauss, continued especially by Johannes Weiss and Albert Schweitzer in the 19th century, and continuing in the 20th and 21st centuries now from Karl Barth to Rudolf Bultmann to Gunter Bornkamm to Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan to E.P. Sanders, among scores of others, make for fascinating reading, but in the end do not help me to discover what the Gospel writers were finally after. No matter how clever my use of the tools of biblical analysis—from historical criticism to form and source criticism to various sorts of literary criticisms to multiple kinds of sociological criticisms, among other approaches—the fact remains that the Gospel writers were not in fact writing history primarily. Mark, I am convinced, was writing a Gospel sermon, drawing his readers into the carefully structured plot, forcing them to conclude his story with their own lives, because the three women when faced with the empty tomb, “said nothing to anyone.” Someone has to tell the story just read, and that someone is you and I!

Matthew and Luke perhaps lean more toward a fuller portrait of the man Jesus, adding parables and wisdom sayings to Mark’s leaner figure, but they too are not writing history, but theological history at best, with a heavy interest on the theological side of the equation. John is in another league altogether, essentially abandoning historical interest, while throwing a bit of it around, for a rich theological picture of the word made flesh, a Jesus always aware of all things, always three steps ahead of anyone else in the story. When I read John, I often picture Jesus about two feet above the ground, floating from place to place; well, after all he is God, as John says again and again!

Why is it important for me to get the genre of the Gospels right? If I am unaware of what I am reading, I am inevitably in danger of asking the wrong questions. If they are not writing history per se, then why should I ask of them questions of history? When I read a textbook of Hebrew grammar, I do not ask questions of the prose style of the textbook; I search for ways to improve my understanding of the ins and outs of Hebrew grammar. In the same way, when I read the Gospels, I want to take with great seriousness the goal of their writing, as much as I am able to discern that goal.

The Gospel of Mark is the parade example of this concern for me. The history of my own study of Mark’s Gospel makes the point. When I was in seminary and graduate school from 1968-1974, I learned from my very learned professors of New Testament that Mark was the poor relation among the far more valuable Matthew and Luke, among the Synoptics, and paled in relation to the high-flown John. His Greek was weak, he had few of the wonderful parables of Jesus, and his ending was ridiculous, surely something missing from the final scroll. However, in the ensuing 50 years, Mark has been read as a literary whole, with eyes out for plot, character, and point of view, in short a literary wonder of historical fiction, that enables us to see and appreciate what he was about in his composition. In other words, once I stopped peering through Mark’s words to seek a fleeting glimpse of some history of Jesus, I was able to step back and see the whole piece and could then evaluate its qualities on its own terms, rather than use it for a search for history that the work itself could not easily sustain. By always looking for the trees, I simply could not see the forest with its majestic beauty and its possible relevance for my life now.

I readily grant that for many Christians it is distinctly difficult to give up looking for the “actual words of Jesus,” many of which have been sustaining for their faith. Those red-letter editions of the Bible, where all the words of Jesus are marked in crimson for those who seek him, are not easily discarded. Still, we finally cannot know the “actual words of Jesus;” they are not accessible to us and never were. What we can know is the picture of Jesus and his age created by the genius of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John. It is their Jesus we can know, not the historical Jesus, who is lost in the mists of the past. Yet, surely, it is this Jesus, this Gospel Jesus, not some supposed man of history, that has in fact been the one we have staked our lives on, the spinner of unforgettable tales, the speaker of wisdom, the lover of the unlovable, the challenger of the authorities, the one finally willing to die as a sign that that love cannot be defeated, and the one raised by God as the proof that the rule of God can and will triumph on earth as it is in heaven.

In Schweitzer’s magisterial volume “The Quest for the Historical Jesus,” the scholar Schweitzer summarizes superbly all the writing of the 18th and 19th centuries dedicated to the search for the Jesus of history. His conclusion is justly famous, representing as it does a summation of a certain liberal notion of who Jesus can be for modern believers. It was obviously a very valuable conclusion for Schweitzer himself, as the remainder of his life was spent in the service of many marginalized people in Africa, living out his discovery of who Jesus was, according to the Gospels that he had read so carefully. I love his words at the end of his search (1906).

“He comes to us as One unknown, without a name, as of old, by the lakeside,

He came to those men who knew Him not. He speaks to us the same words: “Follow thou me!” and sets us to the tasks which He has to fulfill for our time. He commands. And to those who obey Him, whether they be wise or simple, He will reveal himself in the toils, the conflicts, the sufferings which they shall pass through in His fellowship, and, as an ineffable mystery, they shall learn in their own experience Who He is.”

Those poetic words may not completely summarize what I have learned from my reading of the Gospels as historical fiction, but they come pretty close. I trust your reading may yield equally powerful goads to follow this Jesus in your own journey toward the realm of God.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)