I propose to address the Book of Job over the next six essays of this blog. In this first look at Job, I want to assess the state of the use and understanding of the book among people in the church and synagogue. Of course, I cannot know all the ways in which Job has been used and is being used in modern religious experiences, but I can offer a brief history of that use, and can then extrapolate a reasonable series of conclusions of what the book has become in the 20th and 21st centuries of our own time. The reason I chose the title that I did is to claim that the genuinely radical power of the ancient book has rarely been employed in the modern church/synagogue. Hence, I suggest that the book has been in effect “lost” to us, and that that loss is tragic in multiple ways. I know that we need Job in our time, but a Job that is revealed as the astonishing and nurturing and challenging treasure that it is.

I propose to address the Book of Job over the next six essays of this blog. In this first look at Job, I want to assess the state of the use and understanding of the book among people in the church and synagogue. Of course, I cannot know all the ways in which Job has been used and is being used in modern religious experiences, but I can offer a brief history of that use, and can then extrapolate a reasonable series of conclusions of what the book has become in the 20th and 21st centuries of our own time. The reason I chose the title that I did is to claim that the genuinely radical power of the ancient book has rarely been employed in the modern church/synagogue. Hence, I suggest that the book has been in effect “lost” to us, and that that loss is tragic in multiple ways. I know that we need Job in our time, but a Job that is revealed as the astonishing and nurturing and challenging treasure that it is.

I must necessarily be overly simplistic as I enumerate the various ways that Job has been appropriated through the many years of its reception in the church. It is fair to say that Pope Gregory the Great’s vast attention to Job (540-604CE) was the hallmark of Joban reading until the time of the Middle Ages. His Moralia was hugely influential in the ways that the Latin Church approached both theology and ethics, and his essentially allegorical use of Job provided numerous examples of his interests, most particularly in the way that Job served as the very model of fortitude and patience. That emphasis during those one thousand years has continued right into the modern world. In addition, in the period prior to the Renaissance (15th-16th centuries), the church for nearly all of its interpretive life was especially concerned with the more traditional Christological portions of the Hebrew Bible. Because of the heavy focus on the holy days of Christmas and Easter, the Psalms and the book of Isaiah grabbed the bulk of scholarly attention. But with the rise of humanism, readings of the Bible began to be increasingly separated from the ecclesiastical straitjacket imposed by earlier scholars.

In the period of the Enlightenment, beginning in the 15th century, Job became the model of the rational man, who struggled with reason and experience against the strictures of dogma. The Job of the Romantic era (17th-18th centuries) became the sad human figure, one longing for something greater than the finite and dangerous world in which he lived. In the 20th century, Job was humanity condemned in an absurd world, the very essence of the existentialist dilemmas posed by Sartre and Camus, depicted on stage by Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” and McLeish’s “J.B.” It is easy to see that Job’s story has been fully adaptable to whatever needs a given age has asked of it.

Our own time is no different. It is of course common to conclude from this brief summary of interpretation that every Bible reader sees in the text only what she wishes to see; your Bible is thus quite different from mine. There is truth in that comment, but only a partial one. Surely, not every reading of any piece of literature is as valuable or noteworthy or true as any other; there are after all wrong-headed and poor readings that can and have been made. A reading that does not take full account of the actual words of the text, one that focuses too narrowly merely on part of a piece, must necessarily fall short of a worthwhile and trustworthy account of that piece. It is my contention that too many traditional readings of Job have done just that, namely centered attention on this or that section, employing this or that lens (Christian, feminist, materialist, among many others), excluding whole sections of the text, claiming they are “secondary” or “unreadable” or “not original” to the whole 42-chapter book. Anyone who would read Job must take account of all 42 chapters. There are simply no translations of the book of any age that do not include those chapters in roughly the order they appear in the Hebrew Bible, though there are interesting expansions and contractions in several of those translations. I conclude that we need to read the book we have, however awkward some of the material in that book appears to our eyes. I readily grant that a fair amount of the Hebrew is quite difficult, indeed may be the most difficult in the Hebrew Bible; it has been said that fully 10% of it is obscure enough to be judged unreadable. Still, we can sustain the thread of the tale, and that is what we must do as we work our way through it.

And now, finally, I come to the reason once again for my contention that Job has been lost. I wish to say that I think Job was written in the Babylonian exile of Israel, that 6th century BCE time when all theological bets were off, when the promises of YHWH had been dashed, when land and temple and king were apparently lost forever, when a long future in an unknown foreign place seemed to be all an exile could expect. I admit that there is precisely no internal evidence of this conclusion, no place in the words of Job that point to any particular time in Israel’s history. Still, the cauldron of exile is exactly the time that would give birth to such a book. If YHWH’s promises have been abrogated, if the gift of land and king and temple has evaporated, if YHWH now seems silent and distant and seemingly unconcerned with Israel’s future, a deeply and darkly questioning book may be called for. However, at the very same time, another writing appeared, one more certainly attached to Israel’s exile, namely the soaring poetry of 2- Isaiah. I contend that these two authors, Job and 2-Isaiah, were in exilic dialogue with one another, and that 2-Isaiah was the victor in the contest for Israel’s soul that ensued. In effect, Job was first lost not long after it was composed, some 2500 years ago, because the “answers” it offered to the exiles of Israel were not seen as hopeful, as traditional, as winsome as those that 2-Isaiah provided.

Let me give two brief examples of what I mean. Isaiah says in more than one place, but especially in Is.45, that no one has any right to question the work of YHWH in the world. Hilariously, he likens anyone who dares question YHWH to a pot who complains to its maker that he forgot to make the pot’s handles (Is.45:9), or to a man having sex but is still asked what he thinks he is begetting by that action, or to a woman, laboring to give birth, who is asked just what she expects to emerge from her womb (Is.45:10). And Isaiah concludes, “Will you question me about my children or command me concerning the work of my hands” (Is.45:11)? The obvious answer to this rhetorical question is a resounding no.

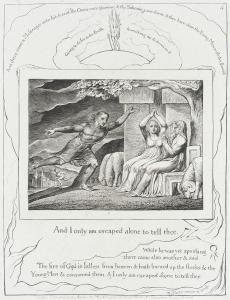

In contrast, the entire book of Job is one continuous questioning of the actions of YHWH. Job has done what he understood YHWH wanted from him, namely rich sacrifice (Job 1:5), along with unimpeachable moral behavior (Job 31:1-34). Yet, his reward for all this, far from YHWH’s affirmation, is YHWH’s hatred and attack. Isaiah warns that no one may question God, but Job questions God again and again, the result of which is God’s appearance to Job at the story’s end.

Another more detailed example of the connections between the books is to be found in the famous Job 19:25. Handel’s ubiquitous oratorio, “The Messiah” fixed this text in our ears as a reference to Jesus, who is in Christian theology our “redeemer,” as the KJV translates the Hebrew word, go’el. That noun happens to be 2-Isaiah’s favorite descriptor for YHWH; he uses it no fewer than nine times in his work. For Isaiah, YHWH is the go’el of Israel, its redeemer, the one who will make Israel whole again after its time of exile. But for Job, the go’el is plainly not God, despite what Handel and many other readers have assumed. In a later essay I will explain how I think Job’s author employs the word; he intends it to mean something radically different than Isaiah does.

Let me repeat my contention: Isaiah won the hearts and minds of Israel as he gave them the hope of a YHWH who was still with them, a YHWH who would again free them from bondage as had happened in their great escape from the clutches of pharaoh, a YHWH that must be completely free and unquestioned to do whatever it is that YHWH proposed to do. It was in the main that YHWH who went back with the exiles to Israel and thus who served as their God in the succeeding ages. And consequently it was that God who was spoken of in later Judaism and emergent Christianity and became the traditional God who was primarily hymned and preached down to our own time. The God who invited questions, who withstood and welcomed the withering criticism of the furious Job, tended to fade into the background of later reflection. That rebel Job was replaced by the patient one, the persistent one, the pious one, who “almost” blasphemed his God, but who in the end was rewarded for his piety after all. Hence, the Job of the biblical book faded away under the evident need to fit him into the dogma of the church and traditional synagogue, though I think it fair to say that rebel Job has found his voice in some modern synagogues despite the more traditional Judaism’s attempts to silence him.

In the essays to come, I will try to present rebel Job once again, the questioning Job, the Job who is not rewarded for traditional piety, but who is given a vision of YHWH that is new and fresh and wonderfully unconventional, a YHWH that I argue we need in our time, a time of climate catastrophe, pandemic, and an uncertain future. I hope you will join me in the search for that Job, the Job who has almost been lost to us.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)