During this pandemic time, my church has been offering each Tuesday and Thursday evening a brief prayer service, led by one of the pastors, consisting of prayer, brief solo song, and two readings from the Bible, keyed generally to the Revised Common Lectionary. The pastor stands in the empty sanctuary, using an I-phone for delivery of the 15-minute service. It offers a traditional and calming experience in these days, when long tradition and sources of calm can be of inestimable value for those of us still isolated in our Los Angeles homes. Unfortunately, a Bible reading without any comment, however traditional that may be for such Vesper services, last night was extremely jarring and was not at all comfortable for at least one of the listeners—namely, me.

During this pandemic time, my church has been offering each Tuesday and Thursday evening a brief prayer service, led by one of the pastors, consisting of prayer, brief solo song, and two readings from the Bible, keyed generally to the Revised Common Lectionary. The pastor stands in the empty sanctuary, using an I-phone for delivery of the 15-minute service. It offers a traditional and calming experience in these days, when long tradition and sources of calm can be of inestimable value for those of us still isolated in our Los Angeles homes. Unfortunately, a Bible reading without any comment, however traditional that may be for such Vesper services, last night was extremely jarring and was not at all comfortable for at least one of the listeners—namely, me.

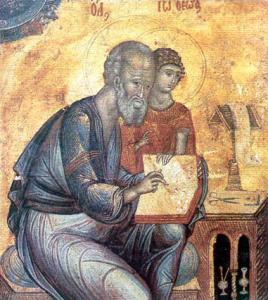

The text was John 8:39-59 and recounted a dialogue between Jesus and what John calls a group of “Jews who had believed in him” (John 8:31). I am fully aware of two facts about the Gospel of John. First, it is wholly unlike the other three Synoptic gospels in numerous ways, expressing its narrative about Jesus in high-flown philosophical- theological language. In John, Jesus is “the Word” who was “at the beginning,” and because John avers that the “Word was God,” clearly for him Jesus is precisely God in the flesh, the living example of the incarnate word, a foundational notion of much Christian theology over the centuries. It could easily be said that John’s gospel forms the bedrock of much later reflection on the nature of Jesus as second person of the Trinity. Such language is quite foreign to Matthew, Mark, and Luke; any reading demonstrates those differences. Second, John displays a very negative attitude toward the Jews in his work, aligning them with evil, and even the devil himself, as in this text (John 8:44). I contend that John has much to answer for when it comes to anti-Judaism, a stance that leads directly to a virulent anti-Semitism, whose horrors were played out most terribly in the last century’s outbreak of murder against the Jews of Europe, perpetrated by the Nazis and their fellow thugs. How can one read this text from John, and not conclude that the Jews plotted against Jesus, plotted to murder him, and thereby demonstrated clearly that they were literally worshippers, not of God, but of the “father of lies,” as John puts it at John 8:44? Due to John’s enormous and ongoing influence on the ways that Christians view their relationship to Judaism, just what are we to do with this text in the 21st century church?

Various attempts have been made to soften the obvious harshness of this Johannine language. Some “translations,” that are in reality certainly ideological interpretations, render the word “Jews” with “religious authorities,” for example. This is an attempt to suggest that not all Jews opposed the ministry of Jesus, which is an historical fact. Indeed, nearly all of Jesus’s early followers were Jews! However, not all Jews found Jesus’s message acceptable, and conspired with their Roman overlords first to combat and constrain the movement begun by Jesus, and finally to have him killed to silence him and his followers. Yet, this translation does not at all solve the problem of this text in John 8, since it explicitly states that this dialogue is between Jesus and “Jews who had believed in him.” Apparently, says John, even those Jews who had a favorable response to Jesus eventually found what he had to say unpleasant or uncomfortable, or perhaps even blasphemous. These Jews who formerly “believed in him,” end the theological debate by grabbing stones to throw at him, a sure sign that his words have signaled to them blasphemy (John 8:59). Just what has he said that makes these original advocates turn into killers?

The lengthy dialogue about Jesus’s relationship to Abraham, that patriarch that the Jews name “their father” (his very name includes the Hebrew for “father”) concludes with the famous claim by John’s Jesus, “Very truly, I tell you (John’s common phrase that announces a crucial theological claim about Jesus) before Abraham was, I am” (John 8:58). And when that comes out of Jesus’s mouth, the stones begin to fly, a stoning that Jesus somehow escapes.

Anyone reading this text in 2020 simply cannot accept its surface meaning, a meaning that suggests that Jesus believes that these Jews are from the devil. If the text is so read, it is little wonder that the Roman Catholic Church did not remove from its canons of belief until 1965 at the Second Vatican Council that the Jews were “Christ killers,” and that no pope entered a Roman synagogue until our own 21st century, though the building was an easy walk to the Vatican. If any text cries out for its historical context for a fuller understanding, this John text is one.

If John is written late in the first century CE, and most scholars agree that is the case, and is the last of the gospel accounts, it appeared during the growing separation between Jews and Christians. Until very late in that first century, Christians worshipped when Jews did, and regularly in synagogues. As Christian communities grew and spread throughout the known world, and as their theologies increasingly coalesced around belief in the divinity of Jesus, “The Word as God,” and as Jesus himself became an object of worship, rather than merely a pointer to the worship of God, many Jews found these ideas unacceptable and began to expel Christian believers from their midst. Was Jesus the Jewish Messiah, or not? Clearly, many late first century Jews simply could not believe in the Messiahship of this Palestinian rabbi for any number of reasons, the main one being that with his coming and his death exactly nothing changed in the world. The Romans still were in control, the poor were still poor and the rich rich, and the future seemed to offer nothing drastically different. Was not Messiah to come and change the world as we know it? Whether Jesus was still alive following a supernatural resurrection, or whether he was dead and cold in a forgotten tomb, the fact was that everything remained as they were before his ministry. The wild Christian claims had little traction with Jews who hoped for much more from their Messiah, thus these pesky Christians became only irritants and annoyances for many Jews who had had more than enough of their idiotic claims about their Jesus.

It is in that climate that John wrote his gospel, a growing divide between Jews, some of whom were initially attracted to Jesus, and an emerging Christianity that demanded belief in Jesus as God, according to the theology of John. In the 21st century, we progressive Christians must no longer imagine, let alone say, that Jews are “of the devil.” We know Jews as friends, as fellow believers in the one God of the universe, and when we discuss theology with them, we cannot begin with the less than humble claim

that Jesus is God, and if they do not accept that fact, then they are lost for all eternity. In genuine dialogue, the partners must enter the discussion with the distinct possibility that all may learn something that one did not know before. In fact, one must enter dialogue with the idea that one might be convinced of one’s own error, and thereby be convinced that the dialogue partner has a greater and more useful truth than you have. Modern dialogues simply cannot end with stone throwing, as John’s supposed dialogue does in his chapter 8.

We only learn one clear thing from John 8. Jesus is God, as John 1 proclaimed at the beginning of John’s work, and refusal to believe in that fact makes one “from the devil, the father of lies.” That is a most dangerous and monstrous conclusion, and any reading of this text must admit that fact and understand and express the historical circumstances that led John to so conclude. The text is rooted deeply in its historical context and may never be read without recognizing and saying that clearly and honestly.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)