Because I am a white man, 73 years old, and am thus up to my eyeballs in privilege, as little as I recognize it or acknowledge it, I today, in the light of the energetic and ongoing protests against the immediate and pervasive attacks on African-American lives by people in authority in our society along with the systemic racism made all the more obvious by those attacks and by the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, will try to hear a biblical story in rather different ways than I have heard it in my past readings. I do this because I am a person of the Bible, having dedicated my entire scholarly and church life to its exposition and public expression. And because that is true, I feel a deep responsibility to read the ancient texts in the glaring light of the times in which I am living. Those who claim that the Bible never changes have not taken seriously the continually changing contexts in which it by definition must be read. My white privilege, though always present, has now been radically exposed by the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Sandra Bland, among literally hundreds more in my lifetime, making plain the reality that Black lives are over 2 1⁄2 times more likely to be taken by police than white ones. And that terrible fact does not begin to indicate the horrendous ways in which Black lives are daily threatened, harassed, and belittled due only to the color of their skin. I can know absolutely nothing of that constant pain, only because my skin is white.

Because I am a white man, 73 years old, and am thus up to my eyeballs in privilege, as little as I recognize it or acknowledge it, I today, in the light of the energetic and ongoing protests against the immediate and pervasive attacks on African-American lives by people in authority in our society along with the systemic racism made all the more obvious by those attacks and by the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, will try to hear a biblical story in rather different ways than I have heard it in my past readings. I do this because I am a person of the Bible, having dedicated my entire scholarly and church life to its exposition and public expression. And because that is true, I feel a deep responsibility to read the ancient texts in the glaring light of the times in which I am living. Those who claim that the Bible never changes have not taken seriously the continually changing contexts in which it by definition must be read. My white privilege, though always present, has now been radically exposed by the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Sandra Bland, among literally hundreds more in my lifetime, making plain the reality that Black lives are over 2 1⁄2 times more likely to be taken by police than white ones. And that terrible fact does not begin to indicate the horrendous ways in which Black lives are daily threatened, harassed, and belittled due only to the color of their skin. I can know absolutely nothing of that constant pain, only because my skin is white.

Hence, my first job is to listen to that pain from those who endure it. Because of my privilege, I have been the one to lead, to lecture, to receive the accolades of prestige and educational opportunity, for all of which I am profoundly grateful. But it is now time, past time, for me to listen to the voices that are too often muted or silenced. In the same ways that I have tried over the years to learn to hear voices of women, of LGBTQ persons, of Latino/as, so now today I need to focus my ears on the voices of Black people.

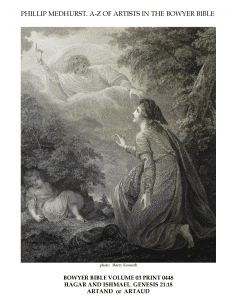

And with that particular need in mind, I turn to a biblical text to test whether that text might contain a word for me for these days, and perhaps a word for you, my white readers. The text comes from the book of Genesis, that rich collection of tales that served the Hebrews as a foundation of their emerging lives as a people. Our text is found in Gen.16, 21, the complex and difficult story of the births of the two sons of Abram and Sarai, Ishmael and Isaac. We have been told long ago in the tale that Abram’s wife, Sarai “was barren and had no child” (Gen.11:30). This fact creates a huge problem for the story, since YHWH has promised that this chosen couple will be the progenitors of a “great nation,” and that their offspring will be as “the stars of the sky and the sand on the seashore.” Well, how is that to be, if the chosen wife is barren?

Sarai has a plan. Her Egyptian slave, Hagar, might serve as a surrogate mother for her. As she puts it to her husband, “YHWH has prevented me from having children; sleep with my slave girl. It could be that I will gain children by her. And Abram listened to the voice of Sarai” (Gen. 16:2). YHWH’s promise is that the child of promise will be created by Abram and Sarai, but the wait is too long, and Sarai feels she is forced to act. And, sure enough, after Abram has sex with Hagar, she conceived. Unfortunately, the result of Hagar’s pregnancy is not hope and joy; instead, “Hagar looked with contempt on her mistress.” And as a result of the haughty behavior of her slave, Sarai screams at Abram, “May the wrong done to me fall on you!” Hagar’s contempt is horrifying and unacceptable from a slave, she shouts. “Let YHWH judge,” cries Sarai. But Abram, ever the one to weasel out of a hard spot (note his unthinking disposal of Sarai into the clutches of pharaoh back in Gen.12), shouts back, “That slave-girl is in your power; do to her however you please” (Gen.16:6)! In other words, it is hardly my problem, whines Abram, rejecting all responsibility in the matter, and handing over the pregnant Hagar to the fury of Sarai. As predicted, “Sarai dealt harshly with her, and she ran away” (Gen.16:6). The verb, “dealt harshly” yields the familiar noun “poor, needy,” one of the categories of persons who must receive special care, according to many of the later prophets of Israel (see Amos, Isaiah, and multiple psalms). Hagar is a victim of oppression, and finds herself pregnant and alone in the wilderness.

An angel of YHWH found her near a spring of water and demands that she “return to your mistress, and submit to her.” In fact, the angel, saying “submit,” uses the same verb that above was translated “dealt harshly.” The angel says in effect to go back in order to receive the same treatment from Sarai that had forced her flight from her in the first place! He then adds that though her life will be miserable, she will receive the very same promise of numerous offspring that was given to Abram and Sarai. The angel then bursts into poetry, telling her that she will name her child Ishmael (“God hears”), because “YHWH has listened to your affliction (that same noun again!)” (Gen.16:11). Ishmael will live a difficult life, “a wild ass of a man, his hand against everyone, ..at odds with all his kin.” Hagar names the God who offers this painful life to her, “a God of seeing,” or “a God who sees” (Gen.16:13).

The travails of Hagar and Ishmael are hardly finished. After she returns to her oppressive mistress, her son grows, but finally, after decades of waiting, Sarai now become Sarah conceives and gives birth to Isaac. And now the contempt in the story pours out of Sarah. After Isaac is weaned, causing a huge celebration, the text says literally, “Sarah saw the son of Hagar, whom she had borne to Abraham, playing” (Gen.21:9). Though the NRSV adds, employing the Greek and Latin texts, “with her son Isaac,” Hebrew lacks the phrase. The mere fact of the joy of a boy playing sends Sarah into paroxysms of fury and contempt, and she again demands that her weak-willed husband “throw the child out of her sight, along with his slave-girl mother” (Gen.21:10). Now in a deeply pathetic scene, Hagar and Ishmael find themselves in the desert, food and water gone. Hagar puts her son under a bush and leaves him there about a bowshot away, not wanting to see him die. Apart from her son, she weeps bitterly. God hears the child’s voice, and again an angel appears, telling Hagar that God has heard (recalling the boy’s name, “God hears”), and will provide for him, since he, too, like Isaac,” will “become a great nation” (Gen.21:18).

The traditional reading of the story focuses its attention on the “child of the promise,” Isaac. After all, the line of the patriarchs is Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; Ishmael has no place in that line. Of course, as we know, Muslims took up the story of Ishmael, rather than Isaac, and made him heir of the promise of Allah. It is Ishmael in the Qur’an whom Abraham nearly sacrifices on the scared mountain and Ishmael who sires a numerous progeny. However, the story itself in Genesis can yield a very different reading, if we hear it with open ears.

The Genesis tale twice affirms that Ishmael, as much as Isaac, is heir to the promise of God. Like Isaac, he will be a great nation; like Isaac, his offspring will be numerous. Both boys are children of YHWH; the story goes out of its way to say that. In the light of Black Lives Matter, might we say that Ishmael’s life, the life born in slavery and in the contempt of the oppressor, Sarah, and expelled to a certain death by that same oppressor, is fully worthy of the care and protection of God? Instead of consigning Ishmael to “the other,” we can see him as the one oppressed by the powers, the one who needs and receives the special care of God, the one who may teach us, the oppressors, about what it means to be “other” in the face of oppression and rejection. Can we not listen to the story of Ishmael as our teacher, as much or more than we can listen to the story of the insider, Isaac? In this day and time, it is Ishmael whom we need to hear, for it is Ishmael who can help us oppressors see the reality of our oppressive acts, to face it squarely, and try to correct the multiple systematic ways that we have created and perpetuated that oppression. O God, I pray, help me to listen to Ishmael, to hear and respond to his cries, as you did, and to seek the ways I can find to admit and seek to lessen my white privilege for the benefit of all people, most especially my black brothers and sisters.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)