The poet we know as 2-Isaiah, who wrote his rich words late in the exile of Israel to Babylon, has played an outsized role in the formation of Christian belief. From his unforgettable opening language in chapter 40, where he urges his hearers to receive YHWH’s “comfort” in their exile, to his mysterious announcements concerning a “suffering servant,” “bruised for our iniquities” and a “carrier of our sorrows,” the author has provided no end of resources for Christians seeking to understand and revere the life and work of Jesus of Nazareth. The celebration of Easter would be much the poorer, if not incomprehensible, without the yearly return to those signal passages from the 6thcentury BCE poet. To be sure, Handel’s ubiquitous “Messiah” would not exist without them.

The poet we know as 2-Isaiah, who wrote his rich words late in the exile of Israel to Babylon, has played an outsized role in the formation of Christian belief. From his unforgettable opening language in chapter 40, where he urges his hearers to receive YHWH’s “comfort” in their exile, to his mysterious announcements concerning a “suffering servant,” “bruised for our iniquities” and a “carrier of our sorrows,” the author has provided no end of resources for Christians seeking to understand and revere the life and work of Jesus of Nazareth. The celebration of Easter would be much the poorer, if not incomprehensible, without the yearly return to those signal passages from the 6thcentury BCE poet. To be sure, Handel’s ubiquitous “Messiah” would not exist without them.

The enduring power of these words rest squarely on a particular theological foundation that may be found clearly demonstrated in the lines from today’s lection. That foundation may be summarized in the following:

“To whom will you compare me,

Or who is my equal?” says the Holy One.

Lift up your eyes on high and see:

Who created these?

The One who brings out their host and numbers them, Calling them all by name;

Because YHWH is great in strength, mighty in power, Not one is missing (Is.40:25-26).

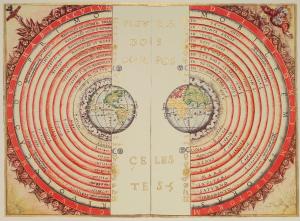

Ringing changes on the second commandment of the Decalogue, Isaiah announces that YHWH has no equal. Fully agreeing with the Ten Words—“You must not have other gods before me”—Isaiah claims that Israel’s God is unique, alone, an incomparable divinity who will brook no rival. And the reason that is true is because Isaiah, like many of those believers in his time, employed a variation of the cosmological argument to buttress his claim. A glance at the stars in the sky should prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that the One who created those, the One named each one and numbered them all, demands exclusive reverence. YHWH’s power and strength are finally unlimited and unchallengeable. As a result, that God can never in any way be questioned or thwarted concerning God’s actions or requirements. In short, for Isaiah, YHWH stands supreme, inviolable, the sole majesty of the universe.

That theological fact makes vs.27 unimaginable.

Why do you say, Jacob,

And speak, Israel,

‘My way is hidden from YHWH;

My justice is disregarded by my God’?

How dare these puny so-called believers question the providence and designs of YHWH? YHWH is a God not be questioned, one never to be talked back to. Isaiah makes the same point hilariously in chapter 45 when he uses two examples to reject any idea that YHWH is to be second guessed. He first announces that to question YHWH is just as if a pot were to say to its potter that she has forgotten the handles (Is.45:9). The second example moves to the world of child-creation. Does anyone ever ask a father while he is engaged in an intimate love-making act, “what are you begetting,” or question a woman in labor, “what do you expect to gush forth from your womb” (Is.45:10)? As ridiculous as it would be to ask such ludicrous queries, so is it equally ridiculous to question the word and acts of YHWH. God is simply beyond discussion, beyond debate. YHWH is God, period, and that is the end of the matter.

Isaiah offers to those in exile a God powerful enough and determined enough to save them and to give them a hope beyond all hope. YHWH is no God in shades of grey, no divinity that opens up to opinion or disputation. YHWH can always be relied upon, trusted, worshipped without fear of failure. It is, I think, that portrait of God that has endured through the ages, the God of absolute omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence. The God of 2-Isaiah has become the God of a vast number of contemporary believers.

However, let me say that this YHWH is not the only one that our Bible presents to us, even though Isaiah’s portrait is by several degrees of magnitude the one most would say is the one that all should affirm and proclaim. However, I, for one, am deeply troubled by this picture of God. Our world is too full of pain and anguish, too rife with uncertainties and struggle, too full of inequities and injustice. I need a rather more mysterious and subtle portrait of God if I am to find a God that might be a God for that sort of world. And the Bible offers a place where such a God might be confronted and addressed, and that would be in the book of Job.

I have long believed that the book of Job and the book of 2-Isaiah were in direct contact and dialogue in the exile of Israel. We can be certain that 2-Isaiah was written during that crucial period in Israel’s history, but the historical provenance of the book of Job has never been as clear. My suggestion that its origin is exilic arises from this central theological concern that the cauldron of exile certainly engendered. After Judah was soundly defeated by the armies of Babylon, after the great temple of Jerusalem was reduced to a pile of stones, after the king was blinded and herded off to Babylon with his court and closest retainers, after the long-promised holy land was ripped away from the people, after the cream of Judah was ensconced in Babylon, ghettoized near the river Chebar, all notions of who YHWH was for them were now up for grabs. Isaiah’s rather traditional answer was surely only one among several in such a time of turmoil. Job’s answer to the issue of YHWH was quite different, a minority report perhaps but one that must have attracted some troubled believers whose idea of Israel’s YHWH had been shaken to its core. All bets were off when all the usual certainties had become suspect. In a world filled with confusion and fear, the resort to Isaiah’s view of YHWH was simply not satisfactory for everyone.

I have elsewhere, both in a long dissertation of 1975 and a rather more accessible book of 1999, have attempted to describe the God I think Job was presenting to the exiles, as well as to us. This is God who far from rejecting questions, invites them, urges those who would claim belief to ask. This is a God who is not so easy to pin down, to explain, to perceive, but one who is elusive, mysterious, often hidden, not readily available at all times and places. This is a God who struggles as we struggle, not one who lives above the struggle and pain but participates in that pain, weeping with us, living with us, loving us in ways difficult of definition.

I appreciate the God of 2-Isaiah and can easily see how that God could be accepted and adored by persons without hope and possibility for any kind of future, a God of power and absolute demand. But that God, for me, is also a God unconnected, removed, distant, a potential tyrant, insisting on devotion without demure, worship without doubt, adherence without wondering. This sort of God may serve others well as big enough to offer genuine help in time of need. I readily admit that I am not oppressed or in deep physical or psychological trouble or in exile from hopes and dreams, realities in my life that make it easy for me to speculate about God in the first place, to call into question Isaiah’s massive God. But so it is with me. I move toward Job’s God who strikes me as a God strange and wonderful enough to encompass the strange and wonderful world in which I live. At least, I would suggest that Job’s God deserves a place in our pantheon of divine understandings. Isaiah may have his say, but his word perhaps ought not be the only or the last word. Such a last word about God has never been said and never will be said, despite Isaiah’s near hegemonic hold on the Christian discussion.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)